In no time, it’ll be here. Will you be ready? The AP® English Language and Composition exam is tough but not impossible. Sure, you must study hard and write as many essays as possible to succeed, but a few handy tips and some guidance goes a long way in preparing you for what to expect. To do well on the AP® English Language and Composition exam, you’ll need to write organized, substantive essays. Specifically, you must write an argument defending your position, using sources provided in the Free Response Question section along with your experience and knowledge.

The AP® English Language and Composition exam consists of two parts. The first consists of 52 to 55 multiple choice questions worth 45% of the total test grade. This section tests your ability to read and answer questions about a host of nonfiction subjects and rhetorical texts. The second section worth 55% of the total score requires essay responses to three questions, demonstrating your ability to analyze, comprehend, synthesize, and cite a variety of nonfiction materials in a well-structured argument. Exam takers have fifteen minutes to read the sources and the remaining two hours to write three essays.

By the time you take the test, you should know how to write a clear, organized essay that argues a claim. Beginning with a brief introduction that includes the thesis statement, you’ll use newspaper, journal, magazine articles, excerpts, or visuals in body paragraphs that support your claim. Pulling quotes and details from the sources, you’ll discuss how your support connects with your thesis statement, and then conclude by reiterating the thesis statement without repeating it. Clear organization, specific support, and full explanations or discussions are three critical components of high-scoring essays.

General Tips for the AP® English Language and Composition FRQs

Your teacher may have already told you how to approach the essays, but it’s important to keep the following in mind coming into the exam:

- Carefully read, review, and underline key to-do’s in the prompt.

- Briefly outline where you’re going to hit each prompt item–in other words, pencil out a specific order.

- Be sure you have a clear thesis or claim that responds to the call of the instructions, given the available evidence for support.

- Identify the sources used as support in your essay by author and title or the letter A, B, or C, etc.

- Use quotes, paraphrases, and statistics—lots of them—to exemplify your points throughout the essay.

- Fully explain or discuss how your examples support your claim. A deeper, fuller, and focused explanation of fewer items is better than a shallow discussion of more items (shotgun approach).

- Avoid making vague, general statements or merely summarizing the sources cited in support of your claim.

- Use transitions to connect sentences and paragraphs.

- Write in the present tense with generally good grammar.

- Keep your introduction and conclusion short, and don’t repeat your thesis verbatim in your conclusion.

The previously-released 2012 sample AP® English Language and Composition exam questions, sample responses, and grading rubrics are valuable learning tools. It’s instructive to analyze the three sample essays for each of the three FRQ essays and zero in on the differences between what AP® readers deem a high, medium, and low scoring essay. In that way, you’ll know what to do and what to avoid come test time.

Free Response Question #1

The subject in the first FRQ of the 2012 exam is the United States Postal Service. The prompt requires exam takers to use three of the seven provided sources to argue the following:

- Whether the USPS should restructure to meet modern demands

- What the USPS should do to meet modern demands

To model successful strategies, you want to break down the CollegeBoard’s three sample answers: the high scoring (A) essay, the mid-range scoring (B) essay, and the low scoring (C) essay. Together, they’re a road map to a high score on the rhetorical analysis essay.

Start with a Succinct Introduction that Includes Your Claim

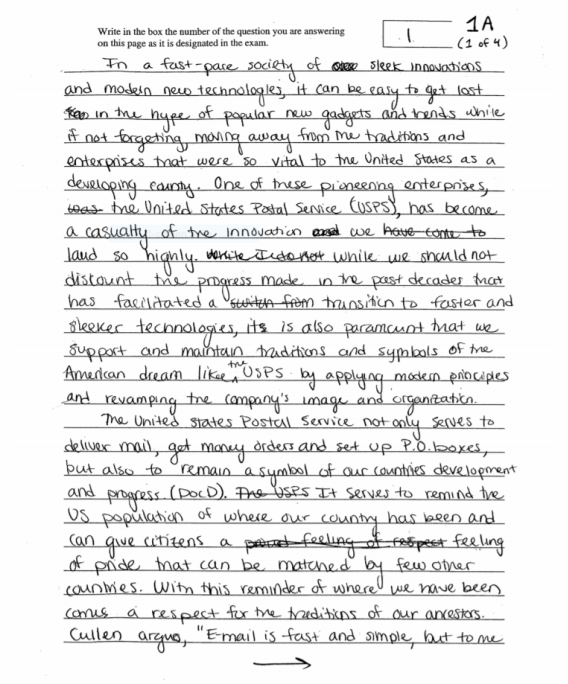

All three essays present their claims in the introductory paragraph. All three also defend the proposition that the USPS should restructure to fit the times. However, the A essay, unlike the other two, structures the introduction to both inform and pique interest. For example, the introduction begins discussing the background of the issue with commonly known facts about the world’s increasing technological dependence. Then, the essay funnels or scopes to narrow to the claim in the last sentence to launch the argument.

The B example also spurs interest with an anecdote to warm the reader to the subject of the essay. Unlike the A essay, however, this one positions the claim in the middle of a long introduction that begins discussing the supporting points that belong in the body paragraphs.

The B introduction previews the essay argument to guide the reader, but not as clearly as the A essay, although far more completely than the C, which merely states the claim in general terms, “for the following reasons”.

In sum, make introductions focused, compact, and precise. Good introductions inform, spark interest, and focus the essay’s main idea in an organized paragraph.

Use Source Facts and Opinions to Support Your Argument Points and Discuss them

The A answer models how to begin each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that furthers the claim and then adeptly supports the topic sentence. In the introduction, the A writer asserts the USPS is a symbol as well as a provider of postal services. Logically, the first paragraph begins with proving that assertion. The second sentence explains and exemplifies how the USPS is a symbol. Afterward, the student seamlessly weaves together assertions, quotes or paraphrases, and discussion in dense paragraphs. Sources are introduced by author or in parenthetical citations. Since economy is critical, the writer makes every sentence count.

Through a methodical process of presenting topic sentences, supported with quotes, facts, opinions, and discussion, the A writer demonstrates keen reasoning and composition skills. The essay proceeds logically from the introduction to the conclusion with well-chosen details and proper sourcing to make the student’s points clear. For example, the writer’s order proceeds from the importance of the USPS to the suggested USPS revisions. Throughout, transitions (“furthermore”) reinforce the relationships between paragraphs.

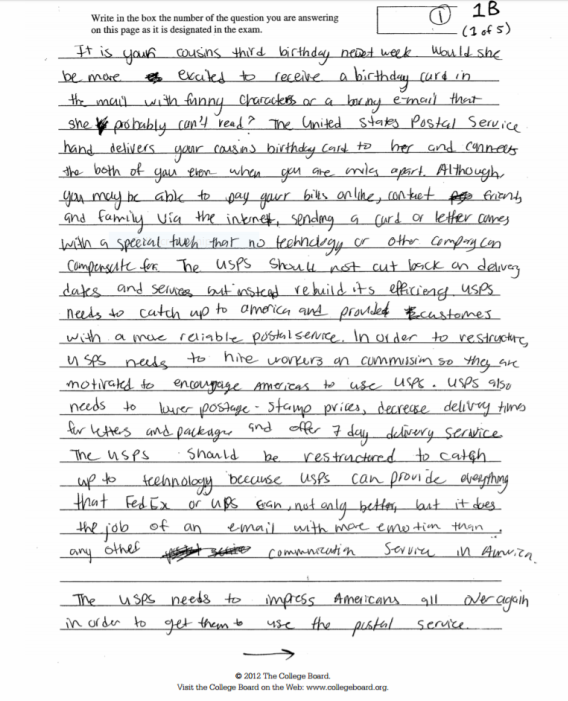

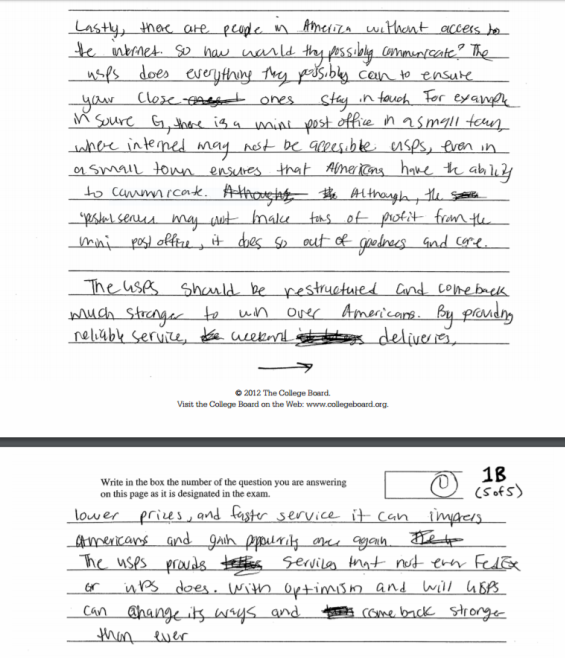

The mid-range sample, on the other hand, struggles to maintain clarity and consistency. Like the A essay, the B essay body paragraphs contain a topic sentence and examples, but the writer explains some examples (the first body paragraph’s point about extending services) but no others (hiring commission and specialized workers). Additionally, the student cites sources inconsistently. The writer doesn’t stick to the A formula of assertion, support, and citation, but generalizes and omits discussion of the main points in support of the claim.

As the CollegeBoard warns, you don’t want merely to summarize sources. The B response does just that in the second body paragraph. Instead of using the source to support the idea that letters are still a source of joy the USPS offers, “to keep in touch with family and friends,” the writer uses anecdotal experience (“I know I’m fiercely tearing away at the envelope”) and summarizes the D source. Moreover, the source is not used authoritatively to support the second point to the claim since the writer just incorporates it into a personal story.

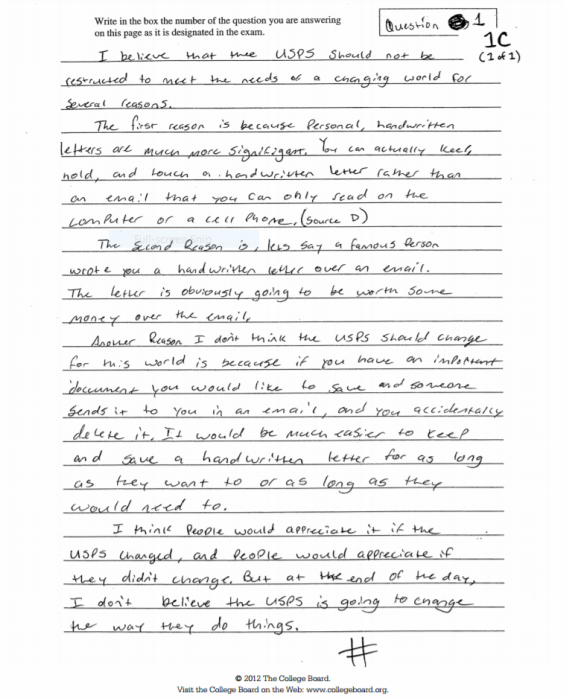

Sample C needs fully developed, clear topic sentences throughout the essay. The first body paragraph starts with an assertion that letters are much more significant as a reason to keep the USPS unchanged. To illustrate, the writer provides: “You can actually feel, hold, and touch a handwritten letter…” without explaining how that’s significant. There’s no discussion tying the example to the topic sentence. Also, all three words–feel, hold, and touch–waste precious time by repeating the same thing (you can feel a letter not an email).

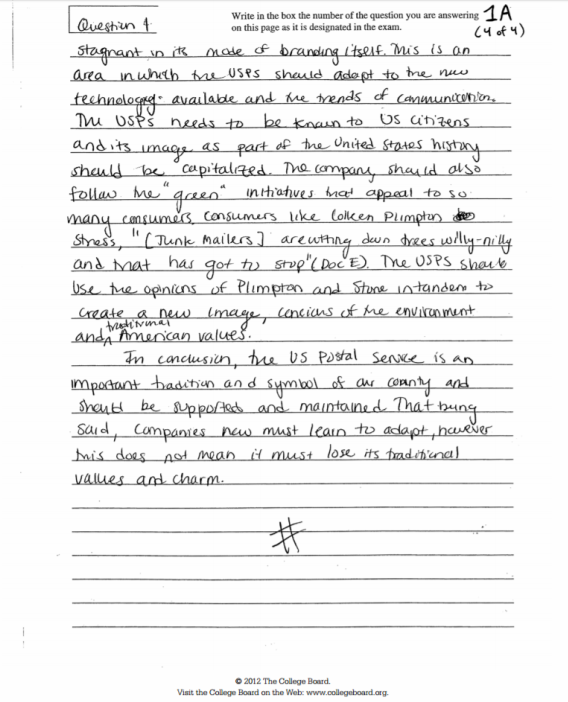

Write a Brief Conclusion

Conclusions leave the reader satisfied and give the writer one last opportunity to cement the argument points and claim in the reader’s mind. If you run out of time, however, omitting the conclusion is not as fatal to your score as writing thin, underdeveloped, disorganized body paragraphs. A quick one or two sentence recap, like the A sample, rounds out thorough preceding paragraphs when nearing the time cut-off.

The A response uses the conclusion to tie together succinctly the three points of the preceding paragraphs: the USPS as tradition, the USPS as symbol, and the USPS modernized but not lost. The writer achieves the dual purpose of recapping and reminding the reader of the claim in the introduction without repeating the claim verbatim.

Conclusions are not for introducing new ideas or points not previously discussed in the body paragraphs. The B essay recaps some but not all points made in the essay but also presents the fact that the USPS provides services other carriers don’t. The disorderly ending doesn’t persuade as well as the A’s shorter but clearer restatement, although it is better than C’s vague opinion that doesn’t restate the claim, propose action, or tie up the essay.

Finally, a conclusion compositionally rounds out your essay so that your reader doesn’t struggle with any part of your essay. By repeating recapped points or fleshing them out with insights, you help the reader pull the argument together and wrap up.

Free Response Question #2

The 2012 AP® English Language and Composition exam, Free Response Question 2, required test takers to read the given commentary by John F. Kennedy from a 1962 news conference and write an essay that does the following:

- Analyze Kennedy’s rhetorical strategies used to achieve his purpose (the assumption being you identify the purpose).

- Support the analysis with “specific references to the text”.

Whereas the first FRQ required test takers to synthesize broad ideas, facts, and writing points in three sources (or portions of them) as support, this second question is different. It requires a closer reading and analysis of one source, forcing writers to tease out meaning from the fewer words and facts in a page and a half commentary.

Introduction and Thesis Statement

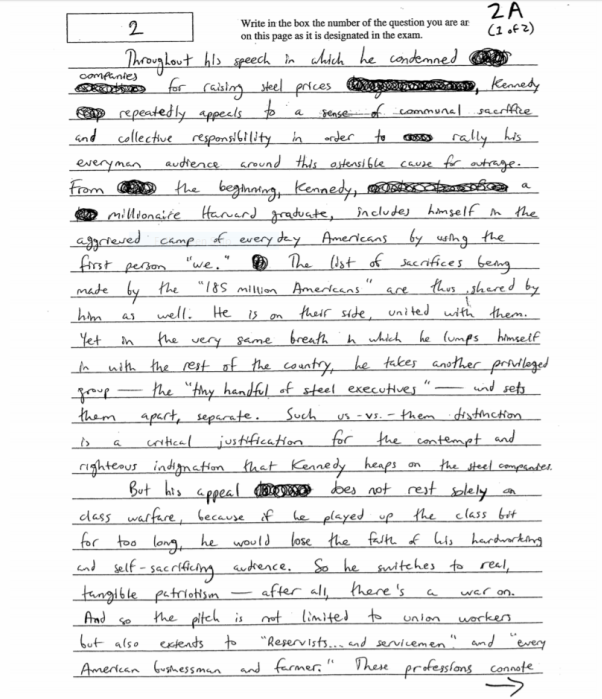

The A Essay

The writer packs the first sentence with strong verbs (“condemned,” “appeals”), details (“raising steel prices”), description (“communal sacrifice,” “collective responsibility,” and “every man audience”), and direction (claim: Kennedy exhorts “outrage” over raised steel prices).

Then, the student identifies the rhetorical stance of the speaker, Kennedy, with one of the “185 million Americans” against the “handful” of greedy “steel executives” and establishes the tone of the argument as “righteous indignation”.

The sophisticated vocabulary, confident weaving of source facts, and keen analytical ability (astute observation about the point of view) lend credibility to the writer’s argument immediately.

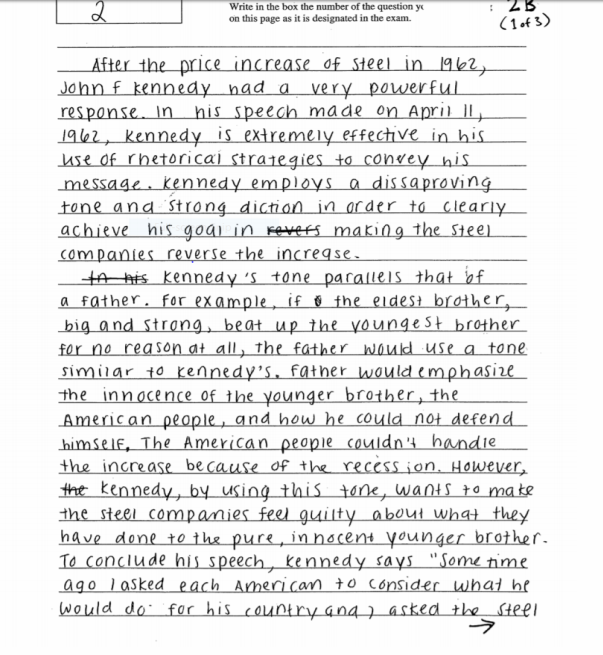

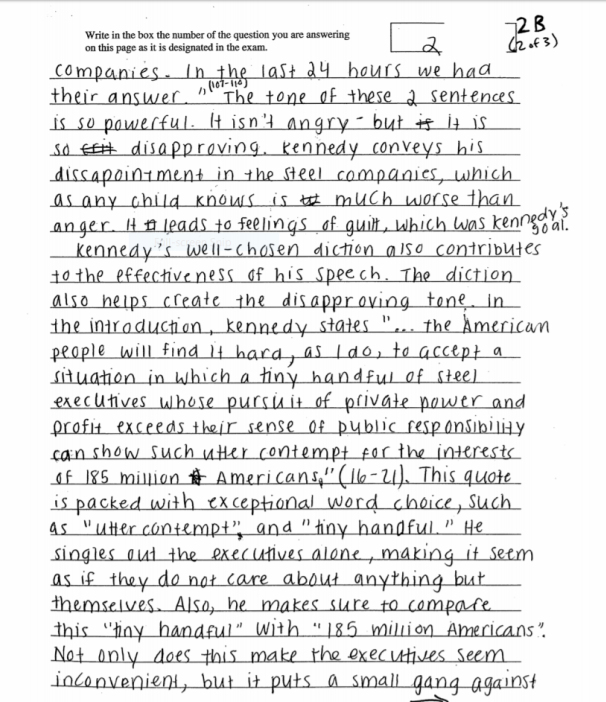

The B Essay

Unlike the economy of the A essay, the B response uses one sentence of a short introduction to repeat the prompt. While the introduction adequately covers the claim and rhetorical strategies, it does so without as much specificity as the A response, opting instead for vague language (“strong diction”) and off-the-mark tone description (Kennedy’s a little more than “disappointed”). By the end of the introduction, the reader understands the essay will touch on tone and diction in analyzing Kennedy’s posited aim to get the steel companies’ price reversal.

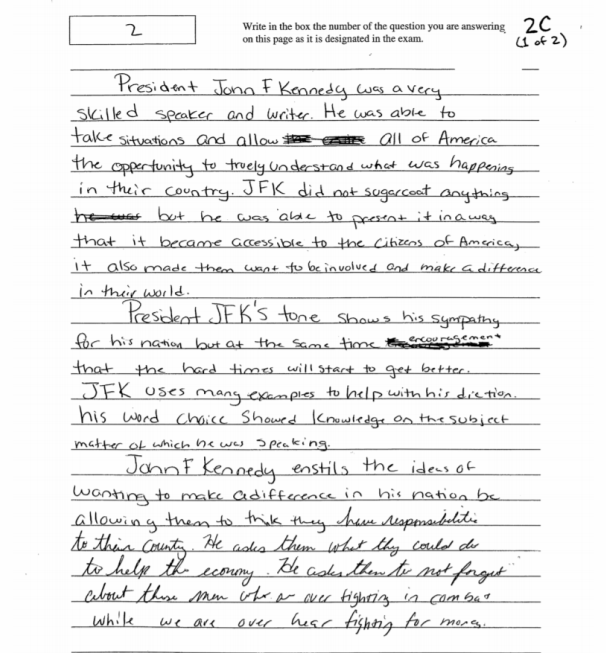

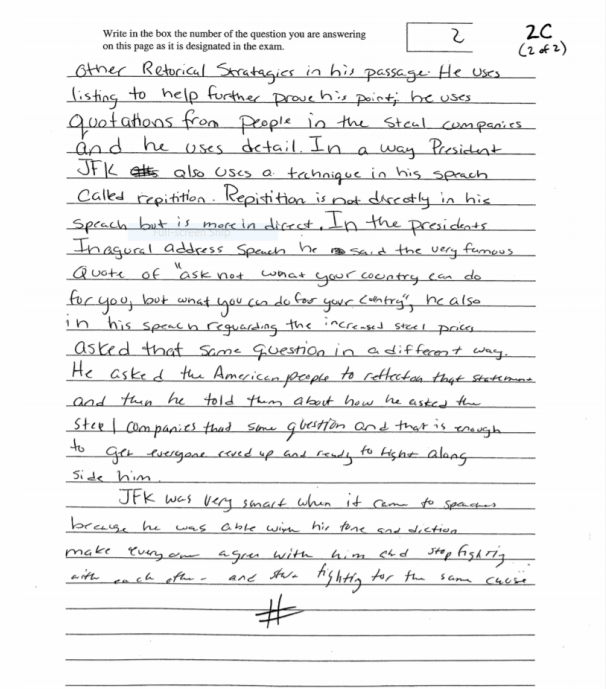

The C Essay

The C introduction lacks specificity and focus. It does not include a claim or address what’s required by the directions. The “it” in “JFK… was able to present it in a way that it was accessible” has no antecedent (what does the “it” refer to?), and the sentence, like the entire introduction, is vague and unclear. The writer shows little understanding of the meaning of “rhetorical strategies”.

Exemplification, Citation, and Discussion in the Body Paragraphs

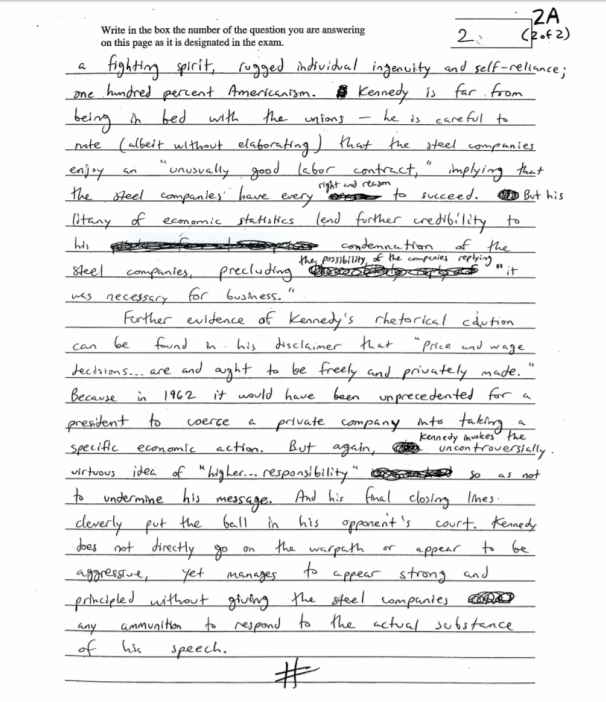

A Essay

Hinging on the word “appeal” from the introduction, the A writer moves in the first body paragraph to Kennedy’s patriotic as well as class appeal. The student cites the text to seamlessly connect the source with the support in a grammatically correct incorporation of quotations into the student’s writing (“but also extends to ‘reservists… and servicemen’”).

The student then expands on the significance of calling upon those specifically addressed in the commentary–servicemen, businessmen, and farmers–to invoke quintessentially American citizens and ideas, hard-working, rugged individualists. The essay proceeds in this highly succinct, fluid pattern of drawing on source language to further each point until the end.

Throughout the body paragraphs, the writer demonstrates confidence and control over language, ideas, and composition skills. The student analyzes methodically, pulling out specific words and devices (“rhetorical caution” in the third paragraph) to reach complex conclusions synthesized from the passage’s language. No statement is left unexplained, and each paragraph begins with a pinpoint focused topic sentences bolstered by transition words that logically connect sentences and paragraphs to cohere all paragraphs to the claim.

B Essay

The first body paragraph begins with the “disappointing tone” from the introduction, a good segue into the body of the essay. However, the writer then spends too much time on an analogy between a parent and Kennedy to the nation, taking up valuable time that could be used to incorporate sources in making the point about tone. The first quoted excerpts come mid-way through the paragraph. The student could have spent more time explaining how the quoted language connotes disappointment rather than continue the hypothetical parent example, which dilutes the point. The essay clearly lacks the compactness of the A model.

The broad language, like “well-chosen diction,” and “exceptional word choice” leave the readers scratching their heads to the meaning. The examples of exceptional words “utter contempt” and “tiny handful” don’t clarify the point. The reader must glean the student’s assertion that the diction is effective since there’s no explanation.

The C Essay

This essay is a shallow analysis, using no direct quotation or specific reference to the commentary until the final body paragraph when the writer finally tackles rhetorical strategies, such as repetition and a restatement of the “Ask not what your country can do for you” reference. The essay primarily summarizes the text content and mentions rhetorical devices but doesn’t exemplify “listing” and “details”. The writing also contains many spelling errors.

Conclusions

None of the essays make grand conclusions, but only the A essay ends concurrently with the writer’s final point and JFK’s parting remark. The other two end with brief paragraphs, the B restating the claim in a sentence and the C winding up with admiration for JFK’s ability to stop people from fighting, a random point. Even though the A essay doesn’t devote a separate paragraph to conclude, it does leave the reader with a sense of completion, ending with the final point in the essay synced to the overall effect of Kennedy’s speech as strong without capitulating.

The Free Response Question #3

The year’s third question poses two quotations, one by William Lyon Phelps, educator, journalist, and professor, and the other by Bertrand Russell, British mathematician, writer, and philosopher, on the nature of certainty and doubt. The prompt requires examinees to write an essay that

- Defends a position about the relationship of doubt and certainty

- Supports the argument with appropriate evidence and examples

Broader than the two preceding questions, this open question requires the student to draw on personal experience or the world to demonstrate the ability to concretize two abstract terms with examples and explanation. The attention to detail, economy, and specificity are critical to successfully anchoring the words to concrete examples. Writers must resist the temptation to define abstract terms with generalizations and vague ideas.

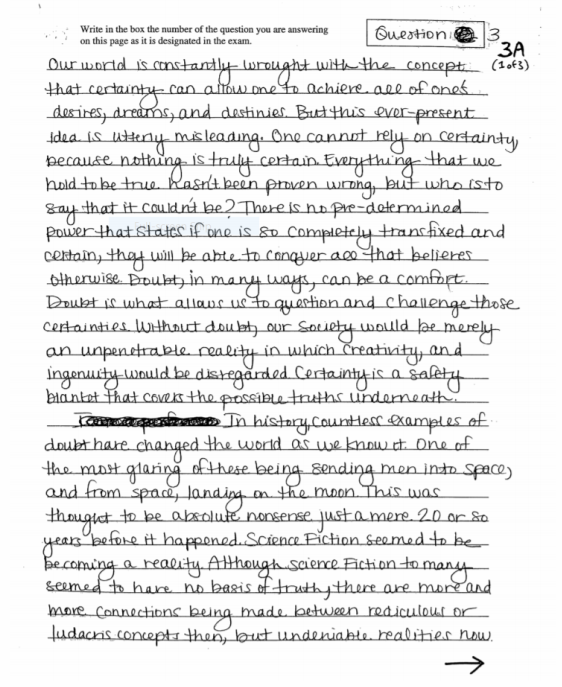

Introductions and Thesis Statements

The A Essay

The top essay gets right to the heart of defending a position. It defends a relationship of certainty to doubt by alluding to the first quotation in summary fashion–certainty is the key to achieving your dreams. The writer then moves on to doubt by first defining it, and then showing its relationship to certainty: “Doubt is what allows us to question and challenge those certainties”. The final sentence of the introduction contains the claim, which all of the preceding sentences lead to in an organized and clear opening to the essay.

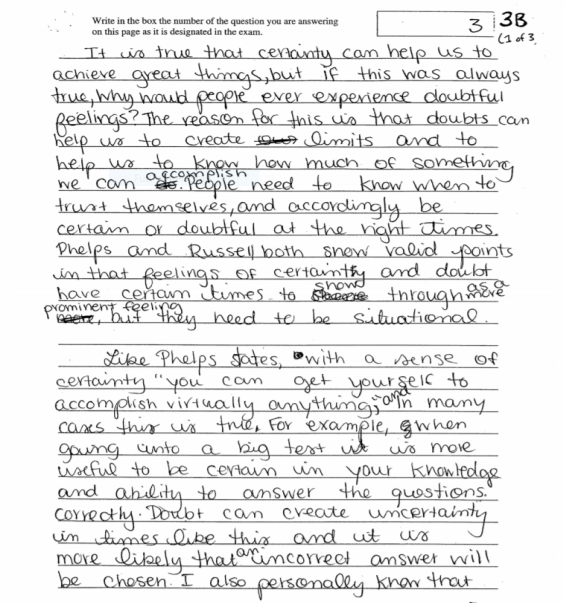

The B Essay

Like the B responses of the two prior sections, the introduction lacks a clear organization, and the language is vague and loose. This short introduction starts out strong by acknowledging a truth about certainty and how doubt fits into that truth. However, by the last sentence, the apparent claim, the ideas become unclear, awash in vague terms like, “the right times,” or “certain times” and entangled in a wordy sentence (“to show through as a more prominent feeling”). Without a clear thesis statement or claim, the reader is unsure where the essay will go.

The C Essay

The third introduction melds into the entire essay, which is one page-long paragraph. The first sentence promises to tackle the certainty concept, but it immediately turns to agreeing with the Phelps quote with one personal anecdote as proof. It’s difficult to decipher where the introduction ends and the essay body begins.

Exemplification and Discussion

The A Essay

Like the model essays before it, this sample successfully organizes each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that seamlessly connects with the preceding paragraph (“In history, countless examples of doubt have changed the world” connects with the last sentence in the introduction about “doubt”).

The next order of business after introducing the claim is locating examples that illustrate the relationship between certainty and doubt. The A writer chooses history. The topic sentence encompasses the main idea that history shows significant instances of doubt, and the following sentences prove that assertion with details about moon landings and other seemingly fictional possibilities that turn into reality. The student elaborates on the idea in a full paragraph that makes the topic sentence clear.

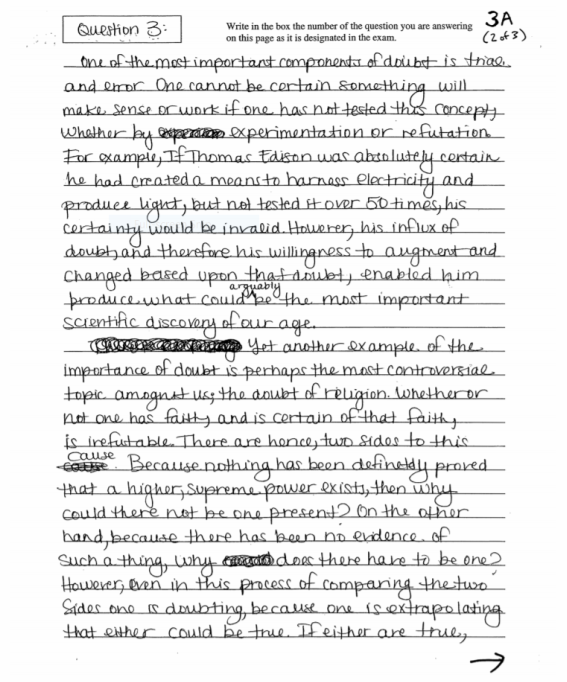

The A essay also contains clear transitions to connect paragraphs together and paragraphs to the thesis statement. For example, the second body paragraph begins, “One of the most important components of doubt is trial and error”. In defending the claim, the writer teases out the meaning and character of doubt.

After exemplifying with Thomas Edison’s discovery based on trial and error, the writer goes on to “another example,” which starts off the final body paragraph. The trail from thesis statement to conclusion is methodical and organized. The order of least to most important–technological advancements to religion–leaves the reader with a strong impression of the writer’s compositional capability and keen insights.

The B Essay

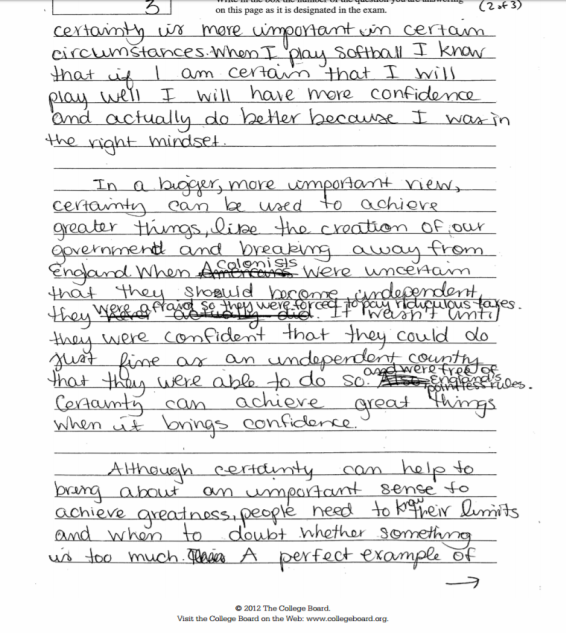

This response also contains insights about the relationship of certainty and doubt (sometimes doubt can mean the difference between living and dying) and examples from history and literature, but the explanations that connect the examples to the point of each paragraph are unclear. The writer uses vague language (“in certain circumstances,” “the right mindset,” “in a bigger, more important view” and less obvious facts (the confidence of the colonists). However, the B writer gets the job done though not without some confusion and work on the reader’s part.

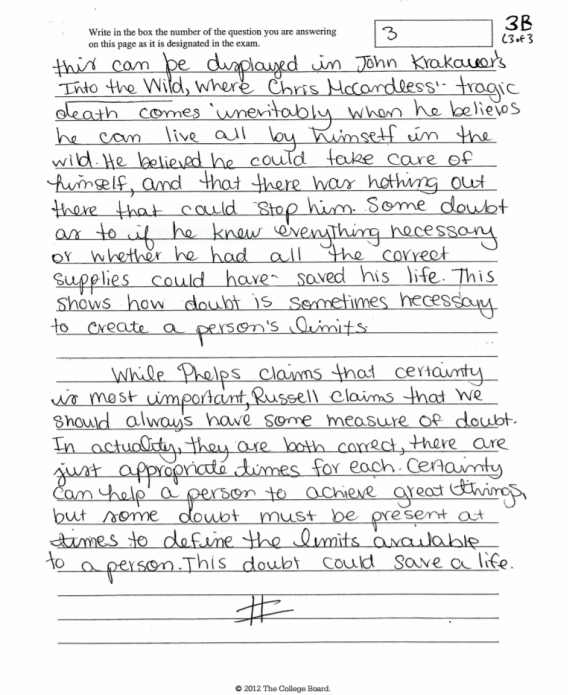

The last example from literature had the potential to exemplify the necessity for doubt, but the reader who hasn’t read the referenced book doesn’t know what the main character did or did not do in the name of confidence. The example is not obvious without a one sentence contextual summary of the character’s behaviors that led to his death might have strengthened the example.

The C Essay

The last example essay uses a personal anecdote of winning a lacrosse game by confidence to agree with the Phelps quote. However, the example is a mere conclusion and a hasty generalization. One incident does not exemplify the broad scope of the quote, which the writer interprets as confidence leads to success.

Without more than a conclusion that the team was confident and the team won, there’s little to no support for the claim, which is that the writer agrees with the Phelps quote. More explanation and detail are necessary to make the example illustrative of the relationship between confidence and doubt. The entire essay needed more: content, order, examples, and paragraphs.

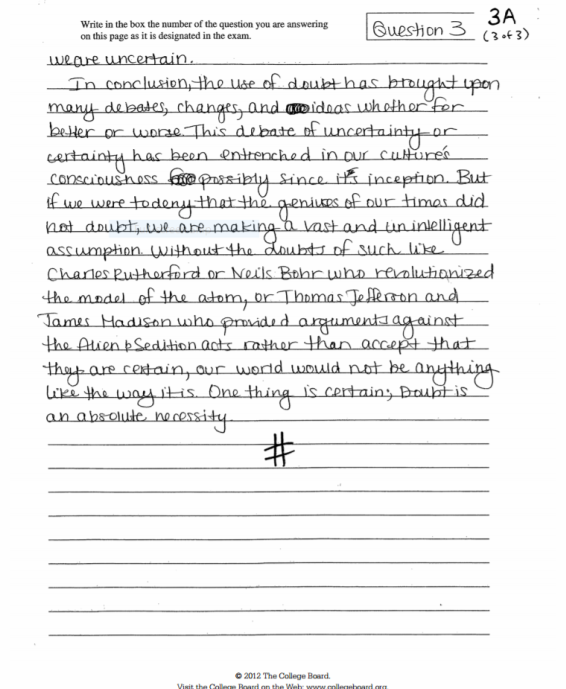

Conclusions

All three essays conclude, but the first one clearly does the best job of winding up the argument. The writer uses the conclusion to reinforce and broaden the reach of the claim that doubt compels creativity to other historical figures not mentioned in the body of the essay. All final examples in the A response support the last comments. They don’t open up a new claim or supporting premise. The last line hammers the essential point home declaratively.

The B and C conclusions, however, don’t satisfy. Consistent with the rest of the essay, the B essay ends vaguely with broad terms that don’t form clear images or ideas: “appropriate time,” “achieve great things,” and “limits available to a person”. The writer needed to specify what’s appropriate, which things, and rephrase “limits available” as the phrase makes little sense. However, the C essay does worse, shifting into second person point of view to instruct the reader in the end. The writer veers off course and doesn’t, in fact, conclude the essay started in the introduction.

Write in Complete Sentences with Proper Punctuation and Compositional Skills

As you can see from all nine samples, writing counts–heavily. Though pressed for time, it’s important to write an essay in concise sentences with words both precise and economical. Choosing strong verbs and adjectives vivify and crystallize your ideas. Fragments and misspelled words cause confusion and weaken your argument. Additionally, sound compositional skills create a favorable impression on the reader.

You want your essay to read smoothly, without the reader having to re-read sentences to figure out what you mean. Using appropriate transitions or signals (furthermore, therefore) to tie sentences and paragraphs together solidifies relationships between sentences and paragraphs (“also”–adding information, “however”–contrasting an idea in the preceding sentence), making your essay organized and clear.

Starting each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that previews the main idea or focus of the paragraph helps both writer and reader keep track of each part of the argument. Each section furthers your points on the way to convincing your reader of your argument. If one point is unclear, unfocused, or grammatically unintelligible, like a house of cards, the entire argument crumbles. Excellent compositional skills help you lay it all out orderly, clearly, and completely.

So by the time the conclusion takes the reader to your parting words, you have done all of the following:

- followed the prompt

- followed the propounded thesis statement in exact order promised

- provided a full discussion with examples

- included quotes, paraphrases, and citations, proving each assertion

- used clear, grammatically correct sentences

- written paragraphs ordered by a thesis statement

- created topic sentences for each paragraph

- ensured each topic sentence furthered the ideas presented in the thesis statement

Have a Plan and Follow it

It takes discipline to lay out an order, a strict time limit for each essay, and stick to them. To score high on the AP® Language and Composition FRQs, practice planning responses under tight time constraints. Write as many practice essays as you can. Follow the same process each time.

First, be sure to read the instructions carefully, highlighting, circling, or underlining the parts of the prompt you absolutely must cover. Then quickly pencil a scratch outline of the order you intend to cover each point in support of your argument. You should write a clear thesis statement, written as a complete sentence, as well as the topic sentences to each paragraph. Then quickly write underneath each topic sentence, the quotes and details you’ll use to support the topic sentences. Then refer to your outline often and follow it faithfully.

Be sure to give yourself enough time to review and revise. Give your essay a brief read over to catch mechanical errors, missing words, or necessary insertions to clarify an incomplete or unclear thought. With time, an organized approach, and plenty of practice, earning high scores on the AP® English Language and Composition FRQs is attainable. Be sure to ask your teacher or consult other resources, like albert.io’s English Literature practice essays, if you’re unsure how to identify poetic devices, prose elements, or just need more practice writing literary analyses.

Looking for AP® English Language practice?

Kickstart your AP® English Language prep with Albert. Start your AP® exam prep today.