Momentum is a fundamental concept in AP® Physics 1 that explains how objects move and interact. It quantifies an object’s motion based on its mass and velocity, making it essential for analyzing real-world scenarios. The conservation of linear momentum helps us understand everything from collisions in car crashes to how spacecraft maneuver in space. Mastering momentum provides a deeper understanding of the relationship between force and motion, a key skill for excelling in AP® Physics 1.

What We Review

What is Linear Momentum?

Linear momentum is the product of an object’s mass and its velocity. It gives an idea of how difficult it is to stop a moving object.

- Definition: Linear momentum is a vector quantity, which means it has both a magnitude and a direction.

- Formula: p = m \cdot v where p is momentum, m is mass, and v is velocity.

Example: Calculating Momentum

Imagine a car that weighs 1,500 kg moving at 20 m/s. The momentum of the car is:

p = 1500 \, \text{kg} \times 20 \, \text{m/s} = 30,000 \, \text{kg} \cdot \text{m/s}The Law of Conservation of Momentum

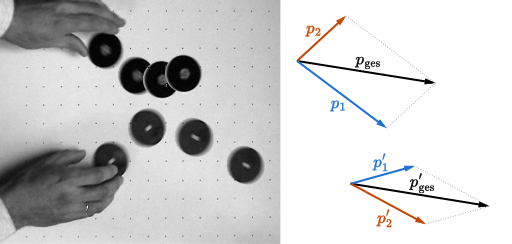

The law of conservation of momentum states that in a closed system where no external forces are acting, the total momentum remains constant. This means if two objects collide, the momentum they had before the collision is the same as after, provided no external force interferes.

- Real-life Example: Consider playing pool. When a pool ball hits another, the total momentum of the two balls before and after the hit stays constant.

The Conservation of Linear Momentum Formula

This principle is mathematically expressed as:

m_1 \cdot v_1 + m_2 \cdot v_2 = m_1 \cdot v_1′ + m_2 \cdot v_2′Where:

- m_1 and m_2 are masses of two objects

- v_1 and v_2 are initial velocities

- v_1' and v_2' are velocities after interaction

Example: Collision Problem

Two ice skaters push off each other. Before the push, skater 1 has a mass of 60 kg and moves at 3 m/s to the right, while Skater 2 has a mass of 50 kg and moves at 2 m/s to the left (toward Skater 1). If Skater 1 moves to the left at a velocity of 1 m/s after the collision, find Skater 2’s velocity after the push.

Solution:

Since the two skaters are moving toward each other before they push off, one velocity must be negative to correctly account for direction. Let’s define motion to the right as positive. If Skater 1 (60 kg) moves at +3 m/s, then Skater 2 (50 kg), moving toward Skater 1, must have an initial velocity of -2 m/s.

Using the conservation of momentum equation:

m_1 v_1 + m_2 v_2 = m_1 v_1' + m_2 v_2'Substituting given values:

(60)(3) + (50)(-2) = (60)(-1) + (50)(v_2') 180 - 100 = -60 + 50 v_2 140=50v_2′ v_2' = \frac{140}{50} = 2.8 \text{ m/s}Final Answer:

Skater 2 moves at 2.8 m/s after the push.

Key Takeaways:

- Direction matters: Since they initially move toward each other, one velocity must be negative to reflect opposite motion.

- Momentum is a vector: Always choose a reference direction and apply signs consistently to avoid calculation errors.

- Conservation of momentum applies in all isolated systems, including situations like this where forces act only between the skaters.

Center of Mass and Momentum

The center of mass is the average position of all the mass in a system. It moves as if all the gravitational forces in the system are acting there.

- How to Calculate: v_{\text{cm}} = \frac{m_1 \cdot v_1 + m_2 \cdot v_2}{m_1 + m_2}

Example: System of Objects

Let’s find the velocity of the center of mass of two masses, 5 kg moving at 3 m/s and 10 kg moving at 1 m/s.

v_{\text{cm}} = \frac{5 \cdot 3 + 10 \cdot 1}{5 + 10} = \frac{15 + 10}{15} = 1.67 \, \text{m/s}Impulse and Momentum

Impulse is when a force acts on an object for a short time to change its momentum. The relationship is expressed as:

- Formula: I = \Delta p = F \cdot \Delta t

Example: Collision Impulse

A ball of mass 2 kg hits a wall and stops. The initial velocity is 10 m/s. If the duration of the impact is 0.5 seconds, find the impulse.

I = \Delta p = m \cdot \Delta v = 2 \cdot (0 - 10) = -20 \, \text{Ns}Practical Applications of Conservation of Momentum

Consider a football tackle where players collide and momentum transfers from one to the other. In vehicle collisions, analyzing momentum helps determine the force experienced. Also, in space, rockets use conservation of momentum to propel forward when fuel gases are expelled backward.

Summary of Key Concepts

Understanding momentum and its conservation is key in physics. It doesn’t just help solve textbook problems but also explains everyday phenomena. Practice regularly to master these concepts and discover more exciting aspects of physics. Remember that:

- Momentum is conserved in isolated systems.

- It connects mass and velocity.

- Impulse is a change in momentum.

- Real-life applications are everywhere, from sports to space.

| Vocabulary | Definition |

| Linear Momentum | Product of mass and velocity of an object. |

| Conservation of Momentum | Law stating that total momentum is constant in an isolated system. |

| Center of Mass | The point representing the average position of a system’s mass. |

| Impulse | Change in momentum resulting from a force applied over time. |

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Physics 1

Are you preparing for the AP® Physics 1 test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world physics problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

Need help preparing for your AP® Physics 1 exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Physics 1 practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.