Rotational motion helps us comprehend how objects like wheels, satellites, and even figure skaters spin. Newton’s Second Law for Rotational Motion is especially relevant in AP® Physics 1 because it introduces a new aspect of motion—one that revolves around axes. This concept clarifies how forces cause objects to rotate. It’s essential to grasp these concepts to tackle more complex physics problems.

What We Review

Basics of Rotational Motion

Let’s start by reviewing the basics of rotational motion. The key variables to know are:

- Angular Displacement: This is the angle through which an object rotates around a fixed point, similar to how displacement is the straight-line distance an object moves.

- Angular Velocity: This is the rate at which the angular displacement changes. Think of it like speed, but in a circle.

- Angular Acceleration: This describes how quickly an object’s angular velocity changes, much like linear acceleration.

Just as displacement, velocity, and acceleration describe linear motion, angular displacement, velocity, and acceleration describe rotational motion.

Example 1: Angular Motion Analogy

Imagine a record player spinning. The record stays in place while rotating around its center. If the record completes a full circle in 2 seconds, find its angular velocity.

Solution:

- Identify the given information:

- One complete circular rotation is 2\pi radians.

- Time for one rotation: t = 2 seconds.

- Use the formula for angular velocity: \omega = \frac{\Delta \theta}{\Delta t} where \Delta \theta = 2\pi radians and \Delta t = 2 seconds.

- Substitute the values: \omega = \frac{2\pi}{2} = \pi \, \text{radians/second}

The angular velocity is \pi \, \text{radians/second}.

Net Torque and Its Effects

Torque is the measure of a force’s ability to cause rotational motion about an axis. It depends on both the magnitude of the force and its distance from the pivot point. The equation for torque is: \tau = rF \sin\theta. Clockwise torque is typically negative. Counterclockwise torque is typically positive.

Net Torque combines all torques acting on an object. Net torque influences angular acceleration, just as net force affects linear acceleration.

Example 2: Calculating Torque

Consider a seesaw with a weight on one side. The distance from the pivot is 2 meters, and the weight exerts a force of 10 Newtons. Calculate the torque.

Solution:

- Formula for torque: \tau = r \times F where r = 2 \, \text{m} and F = 10 \, \text{N}.

- Calculate torque: \tau = 2 \, \text{m} \times 10 \, \text{N} = 20 \, \text{Nm}

The torque exerted by the weight is 20 \, \text{Nm}.

Newton’s Second Law for Rotational Motion

Just as Newton’s Second Law in linear motion states that acceleration is directly proportional to net force and inversely proportional to mass, the same principle applies to rotational motion. Instead of force, we consider torque, and instead of mass, we use rotational inertia (moment of inertia). The fundamental equation is:

\alpha = \frac{\tau_{\text{net}}}{I}- \alpha: Angular acceleration.

- \tau_{\text{net}}: Net torque.

- I: Moment of inertia, an object’s resistance to rotation.

Together, net torque and rotational inertia determine how quickly something spins up or slows down. Based on this equation, we can see that:

- Greater torque produces greater angular acceleration, just like a larger force causes greater linear acceleration.

- Higher moment of inertia resists changes in rotational motion, just as greater mass resists changes in linear motion.

- Torque must be unbalanced to create angular acceleration—if torques are balanced, the object remains in rotational equilibrium.

Example 3: Finding Angular Acceleration

Assume a disk with rotational inertia (I) of 4 \, \text{kg m}^2 and a net torque (\tau_{\text{net}}) of 8 \, \text{Nm}. Calculate the angular acceleration.

Solution:

- Use the formula: \alpha = \frac{\tau_{\text{net}}}{I}

- Substitute the known values: \alpha = \frac{8}{4} = 2 \, \text{radians/second}^2

The angular acceleration is 2 \, \text{radians/second}^2.

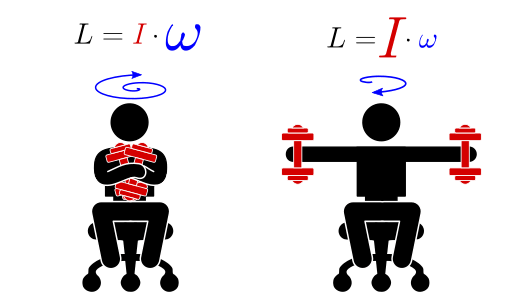

The Role of Rotational Inertia

Rotational Inertia (or moment of inertia) is how much an object resists changing its rotation. It’s influenced by the object’s shape and mass distribution—a solid disk and a hollow cylinder, for instance, have different inertias.

Example 4: Comparing Inertia

Compare a solid disk and a hollow cylinder, each with the same mass and radius.

- Solid Disk: Moment of inertia is I = \frac{1}{2}mr^2.

- Hollow Cylinder: Moment of inertia is I = mr^2.

If m = 2 \, \text{kg} and r = 1 \, \text{m}:

- Solid Disk: I = \frac{1}{2} \times 2 \times 1^2 = 1 \, \text{kg m}^2.

- Hollow Cylinder: I = 2 \times 1^2 = 2 \, \text{kg m}^2.

The hollow cylinder has more inertia, so it’s harder to spin or stop spinning.

Analyzing Combined Linear and Rotational Motion

Certain situations require analyzing linear and rotational motion together, such as when a wheel rolls down a ramp.

Example 5: A Rolling Object

A wheel rolls down a ramp without slipping. Assume a radius of 0.5 \, \text{m} and an angular velocity of 4 \, \text{radians/second}. Find its linear velocity.

Solution:

- Link angular and linear velocity with v = \omega \cdot r.

- Substitute values: v = 4 \, \text{radians/second} \times 0.5 \, \text{m} = 2 \, \text{m/s}

The wheel’s linear velocity is 2 \, \text{m/s}.

Conclusion

Newton’s Second Law for rotational motion helps explain how objects rotate when acted upon by a net torque. To succeed on the AP® Physics 1 exam, follow these key strategies:

- Understand the equation: Know that angular acceleration depends on net torque and moment of inertia. A larger torque increases acceleration, while a larger moment of inertia resists changes in rotation.

- Be mindful of torque direction: Remember that counterclockwise torques are usually positive, while clockwise torques are negative.

- Use the right moment of inertia formula: Different shapes have different values. You don’t need to memorize them, but know how mass distribution affects rotation.

By applying these tips, you’ll strengthen your problem-solving skills, making torque and angular acceleration much easier to tackle on the AP® Physics 1 exam!

| Term | Definition |

| Torque | A measure of the rotational force applied to an object. |

| Angular Velocity | The rate of change of angular position of a rotating object. |

| Angular Acceleration | The rate of change of angular velocity over time. |

| Rotational Inertia (Moment of Inertia) | An object’s resistance to changes in its rotational motion. |

| Net Torque | The total torque acting on an object, determining its angular acceleration. |

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Physics 1

Are you preparing for the AP® Physics 1 test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world physics problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

- AP® Physics 1: 5.1 Review

- AP® Physics 1: 5.2 Review

- AP® Physics 1: 5.3 Review

- AP® Physics 1: 5.4 Review

- AP® Physics 1: 5.5 Review

Need help preparing for your AP® Physics 1 exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Physics 1 practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.