Angular momentum and impulse might sound complex, but they are fundamental concepts in physics with numerous real-world applications. From understanding how ice skaters spin to how planets orbit around the sun, it plays a crucial role. It is key in the AP® Physics 1 course and exam. Grasping this concept and the angular momentum formula will help solve rotational motion problems, a vital part of the curriculum.

What We Review

What is Angular Momentum?

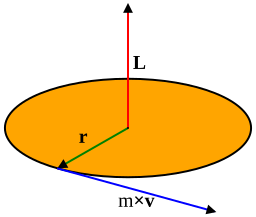

Angular momentum measures the rotational motion of an object, similar in principle to linear momentum but for spinning objects. It is given by the formula:

\text{Angular Momentum (L)} = I \omegawhere:

- I is the moment of inertia, indicating how mass is distributed relative to the axis of rotation.

- \omega is the angular velocity, representing how fast the object rotates.

Additionally, for a point mass, angular momentum can also be described by:

L = r mv \sin(\theta)

where:

- r is the perpendicular distance to the axis of rotation.

- m is the mass.

- v is the linear velocity.

- \theta is the angle between the radius and velocity vectors.

Understanding the axis of rotation is crucial because angular momentum varies with different axes.

Components of Angular Momentum

Moment of Inertia (I)

The moment of inertia is the rotational equivalent of mass in linear motion. It represents how difficult it is to change an object’s rotation. The formula can differ based on the shape of the object. For a solid disc, for example:

I = \frac{1}{2} m r^2You won’t be expected to memorize the formulas for the AP® Physics 1 exam. It is important to be able to explain how mass distribution impacts the rotational inertia.

Angular Velocity (\omega)

Angular velocity tells how fast an object rotates and is measured in radians per second.

Example Problem: Calculating Angular Momentum

Calculate the angular momentum of a 2 kg disc with a radius of 0.5 meters rotating at 10 rad/s.

- Calculate the moment of inertia for the disc: I = \frac{1}{2} m r^2 = \frac{1}{2} \times 2 \times (0.5)^2 = 0.25 \, \text{kg m}^2

- Use the angular momentum formula: L = I \omega = 0.25 \times 10 = 2.5 \, \text{kg m}^2/\text{s}

Calculating Angular Momentum

The formula (L = r mv \sin(\theta)) expands our understanding beyond rigid rotating bodies to point masses.

- r: Distance from the axis of rotation.

- m: Mass of the object.

- v: Linear speed.

- \theta: Angle between the direction of motion and (r).

The sine function accounts for the component of linear momentum contributing to rotation.

Example Problem: Finding Angular Momentum for a Point Mass

A 1 kg ball moves with a velocity of 4 m/s at an angle of 30^\circ relative to a point 3 meters away. Find the angular momentum.

- Identify components:

- r = 3\text{ m}, m = 1\text{ kg}, v = 4\text{ m/s}

- Calculate using the formula: L = r mv \sin(\theta) = 3 \times 1 \times 4 \times \sin(30^\circ) = 6 \, \text{kg m}^2/\text{s}

Angular Impulse

Angular impulse is the change in angular momentum over time. The formula is:

\text{Angular Impulse} = \tau \Delta twhere \tau is torque (a rotational force) and \Delta t is time.

Example Problem: Calculating Angular Impulse

If a torque of 5 Nm acts on a wheel for 3 seconds, calculate the angular impulse.

- Use the formula: \text{Angular Impulse} = \tau \Delta t = 5 \times 3 = 15 \, \text{Nms}

Impulse-Momentum Theorem for Rotation

The impulse-momentum theorem connects torque with the change in angular momentum:

\Delta L = \tau \Delta tThis shows how rotational motion changes based on applied torque over time.

Example Problem: Relating Torque, Time, and Change in Angular Momentum

A spinning top initially with angular momentum of 10 kg m²/s increases to 25 kg m²/s under a torque of 10 Nm. Find the time this torque acted.

- Find change in angular momentum: \Delta L = 25 - 10 = 15 \, \text{kg m}^2/\text{s}

- Solve for time: \Delta t = \frac{\Delta L}{\tau} = \frac{15}{10} = 1.5 \, \text{s}

Graphical Interpretation of Angular Momentum

Torque vs. time graphs help visualize angular changes. The area under the curve equals angular impulse.

Example Problem: Interpreting a Torque Graph

Given a torque vs. time graph with a rectangle (base = 3 s, height= 4 Nm), determine the angular impulse.

- Compute the area under the graph: \text{Area} = \text{base} \times \text{height} = 3 \times 4 = 12 \, \text{Nms}

Conclusion: Angular Momentum and Impulse

Consistent practice with real-world examples—such as spinning athletes, orbiting planets, and rotating wheels—is essential to fully grasp angular momentum. Understanding these principles will strengthen your problem-solving skills and prepare you for AP® Physics 1 exams.

Key takeaways:

- Angular Momentum depends on an object’s moment of inertia and angular velocity.

- Moment of Inertia represents an object’s resistance to rotational acceleration.

- Angular Impulse (torque × time) causes changes in angular momentum, much like force changes linear momentum.

For deeper understanding, explore additional exercises, simulations, and practice problems, ensuring confidence in tackling rotational motion on the exam.

| Term | Definition |

| Angular Momentum | A measure of the rotational motion of an object. |

| Moment of Inertia | The resistance of an object to changes in its rotational motion. |

| Angular Velocity | The rate of change of an object’s angular position over time. |

| Torque | A measure of how much a force acting on an object causes that object to rotate. |

| Angular Impulse | The product of torque and the time over which it acts, equal to the change in angular momentum. |

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Physics 1

Are you preparing for the AP® Physics 1 test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world physics problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

Need help preparing for your AP® Physics 1 exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Physics 1 practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.