Looking for the best list of AP® European History tips? Look no further.

Excelling on the AP® European History exam can be a challenge, but knowing how to study for AP® Euro can help. With only 11.7% of test takers scoring a 5 and another 20.6% scoring a 4 in 2019, AP® European History represents one of the most difficult Advanced Placement exams to score high on. In AP® European History, you will evaluate primary and secondary sources, write specific historical claims and support them with appropriate evidence, and contextualize historical events within their appropriate time period.

While the test may sound daunting, you’ve already taken an excellent first step towards success by visiting our website. We’re here to help you ace the AP® European History exam. Below, we’ve provided a comprehensive list of suggestions for how to study for AP® European History. You’ll find a variety of AP® European History resources and tips as well as clear AP® European History DBQ examples, practices, and more.

What We Review

Overall How To Study for AP® European History: 11 Tips for 4s and 5s

1. Make studying part of your daily routine.

The old saying goes that, “Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it” but it’s also true that, “Those who try to learn five centuries of European History in one night before the test are doomed to fail it.” But seriously, not starting to study until the day or even a few days before this test is a recipe for disaster. Rather than leaving all of your studying until the last minute, make short study sessions a part of your daily routine.

If you don’t believe us, believe the cognitive scientists who research how to study. According to Dr. Yana Weinstein, cramming for tests actually takes longer and results in less learning than simply spending a few minutes each day reviewing what you learned.

2. Just re-reading your notes and textbooks is bad studying.

Once you’ve made studying part of your daily routine, it’s important to consider how you are studying. Some methods are more effective than others, and you want to spend your time doing what works best. One strategy not to use: re-reading your notes and textbook.

Why not? Studies show that re-reading your notes actually ends up taking a lot of time and producing less durable learning than other study methods. Mark McDaniel, co-author of Make It Stick, showed that students who re-read their textbook had “absolutely no improvement in learning over those who just read it once.” So unless you just happen to enjoy reading history textbooks (we do, it’s cool), try out some more effective forms of studying like using flashcards, creating charts that show connections between events, and journaling about what you have learned in class.

3. Think outside of the fact.

The way middle schools teach history set up high school students for failure when it comes to tackling challenging history courses. Rather than memorize facts from your book like you’ve done since middle school, create a framework and general understanding of the core themes from your reading. Believe it or not, knowing the type of bread that XYZ leader liked is not important.

A lot of history books go excessively in depth in regards to the nitty gritty. Learn to selectively read the important bits of information and practice summarizing the key points of your reading by outlining 3-5 key takeaways in your notes on your readings. If you cannot connect the dots, then you will simply craft essays with random “name drops” and “date drops”; as a result, your AP® score will reflect your inability to create a cohesive argument.

4. Try out the SQ3R method.

This is a popular studying technique that can be applied for more than just AP® European History. Francis Robinson originally created it in a 1946 book called Effective Study. SQ3R stands for Survey, Question, Read, Recall, and Review. You can read more about the SQ3R method here.

5. Connect, connect, connect:

In case we haven’t mentioned it enough, AP® European History is all about connecting the dots. Whether you’re just doing your nightly reading or reviewing for your test, it’s helpful and essential that you recognize how events and people in history are interrelated. History is the study of how people interact with one another.

One technique to make sure you are connecting the dots is to write key events or terms on flashcards; then at the end of your reading or review session, categorize your flashcards into 5-7 different categories. You may end up doing this by time period, by a significant overarching event, etc.

A good way to think about this is you have 5-7 drawers, and a bunch of random things lying around in your room. Each thing represents some event or important person in history and you want to fit all the things into one drawer in order to make your room clean again. If the clean room analogy doesn’t work for you, try to think of a way to get in the categorizing mindset yourself and let us know about it!

6. Create a cheat sheet:

While unfortunately you won’t be able to use your cheat sheet on the actual test, you can use a cheat sheet to help simplify your reviewing process as the AP® European History test gets closer. Create a cheat sheet that is flexible and can be added on to—then as the year progresses and you do more and more readings, add to your cheat sheet. Before you know it, you’ll have a handy and hopefully concise reference guide that you can turn to in those last few weeks before the test.

Here are a few examples of what cheat sheets might look like in your history class. Notice that each sheet includes not only key terms and dates but also describes the historical context.

7. Supplement your studies with a review book.

Review books are one of the most important tools for surviving AP® European History. These books are often broken into chapters with summaries and review questions at the end. They also include practical suggestions on how to study for AP® Euro. Typically, they include several AP® European History DBQ examples and at least one full AP® European History practice test. We highly suggest investing in and heavily using one of several highly rated review books.

8. Test, study, test.

In a class that covers several centuries of history like AP® European History, there are going to be some topics that you understand better than others. That’s totally normal, and it shouldn’t scare you. But one key for surviving AP® European History is to spend the time that you are studying on the topics that you are least familiar with. We suggest the test, practice, study workflow.

First, take a short test between five and ten questions on a specific topic. Albert offers high-quality practice questions broken down by topic. Then, review your score. If you did really well, that means you understand the topic and probably don’t need to spend much more time reviewing it.

However, if you struggle, you should spend more time studying that topic and then test yourself at the end to ensure understanding.

9. Hank’s History Hour:

Going along the lines of alternative ways to learn AP® European History, you can also learn a great deal from Hank’s History Hour, which is a podcast on different topics in history. This is a great way to actually go to sleep since you can listen to the podcast while you dose off. Did you know when you go to sleep you remember what you heard last the best when you wake up?

10. Supplement your learning with video lectures:

While YouTube can be a distractor at times; it can also be great to learn things on the fly! Crash Course has some great videos here pertaining to AP® European History. Use them to affirm what you know about certain time periods and to bolster what you already know; then, practice again.

11. Create flashcards along the way:

After you have gotten a multiple choice question wrong, create a flashcard with the key term and the definition of that term. Think about potential mnemonics or heuristics you can use to help yourself remember the term more easily. One way is to think about an outrageous image and to associate that image with the term related to AP® European History.

One of the best ways to use flashcards is through the timeline game. First, create or find a list of the most important dates to remember for the AP® European History Test. Here’s one student who already created a Quizlet with over 60 important dates.

Next, create a flashcard with the event on one side and the date on the other. Afterwards, get together with one to three study partners and treat your flashcards like a deck of cards. Deal five cards to each player with the date side down. Use the remainder of the index cards as a draw pile. Take the top card from the draw pile and put it down in the center of your table and read the event and the data on that card. This card is the first event in your timeline.

Next, each player goes around one by one, adding to the timeline. All you have to do is to say whether the event on your card happened before, after or between the events that are already on the timeline. If you get it right, you will place your card on the timeline in the appropriate slot. If you are wrong, you will also place your card on the timeline but you also draw a new card. The first person to get rid of all their cards wins. See this link for further directions.

Return to the Table of Contents

AP® European History Multiple Choice Review Tips: 9 Tips

1. Pay attention to SOAPSTone.

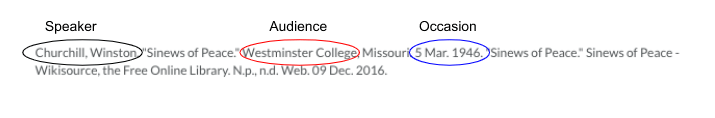

The best way to quickly understand primary source documents is by paying attention to who is writing, to whom they are writing, and when they are writing. This process is often referred to as contextualization, and SOAPSTone is a very handy way of breaking the thinking into smaller bites.

Let’s take a look at one practice problem from Albert’s AP® European History review resource.

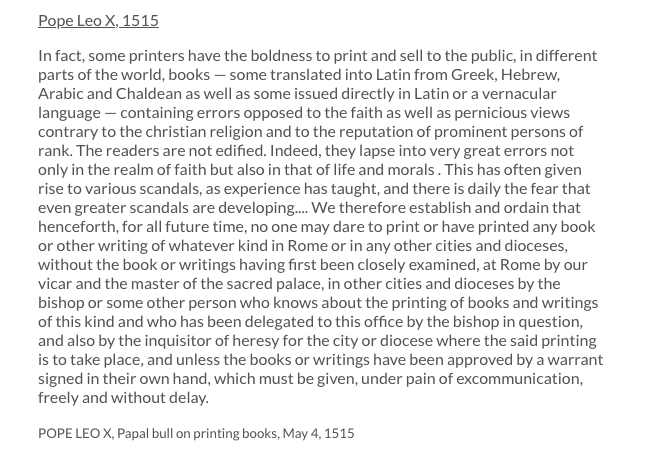

We chose this massive chunk of text for a reason: you can quickly understand what the speaker is arguing by understanding who the speaker is as well as the historical context of the document. Doing so requires only the source line.

An astute student will quickly note that this document was produced by the Pope in the year 1515, just around the beginning of the Reformation. The source line identifies the major topic as “on printing books” and using your historical knowledge about the Reformation, you can make a very solid prediction that the Church will be highly suspicious about the distribution of printed materials. By reading those last eleven words, you’ve set yourself up to better understand the rest of the document.

2. Read the title, key, and axes for all charts.

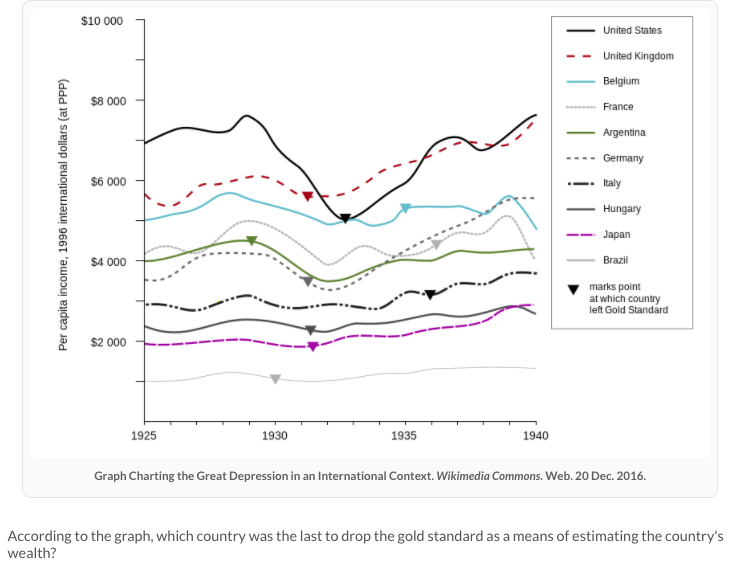

The AP® European History exam will not only require you to read text but also to interpret charts. It may seem obvious, but you must read the key on these charts in order to accurately interpret their meaning.

The question above is really quite challenging on its own: most students won’t remember the year that Brazil dropped the gold standard as a means of estimating their wealth. And yet, students who read the key will notice that that the upside down triangle “marks [the] point at which [the] country left [the] Gold Standard”.

Furthermore, the X-axis clearly represents years. From there, the answer is obvious. The purpose of this question is not to test your understanding of Brazil’s economic history but to make sure that you know how to read a chart, so make sure you use the title and axes to your advantage.

3. Pay attention to the clock.

Many of our students have found the timing of this exam to be extremely challenging. The AP® European History exam allots 55 minutes for 55 multiple-choice questions. The fast pace of the multiple-choice section does mean that you shouldn’t spend too long on any single question. One helpful strategy is to make your best guess and then to return to questions you are concerned about at the end if you have time.

Another helpful strategy is to take several 55 question multiple-choice AP® European History practice tests in advance. Albert has several full-length tests that you can use to practice as well as a whole host of other standards-aligned questions. When you take these tests, set a 55-minute timer on your phone and stop when that time is up.

4. Attempt to answer every question.

If you’re crunched on time and still have several AP® European History multiple-choice questions to answer, make a solid attempt at answering each and every one of them. With no guessing penalty, you literally have nothing to lose.When it comes to the AP® European History test, all multiple-choice questions are weighted equally.

5. Use the Process of Elimination.

When it comes to tackling AP® European History questions, the process of elimination can come in handy if you can eliminate just one answer choice or even two, your odds of getting the question right significantly improve. Remember there is no guessing penalty so you really have nothing to lose.

6. Use your writing utensil.

As you work through the multiple-choice section of the AP® European history test, physically circle and underline certain aspects of answer choices that you know for fact are wrong. Get in this habit so that when you go back to review your answer choices, you can quickly see why you thought that particular answer choice was wrong in the first place.

For example, whenever you see “EXCEPT” on the test, circle it. EXCEPT questions can often throw students off so make sure that you get in the habit of physically circling every time you see the word EXCEPT. This is a technique that you can use for more than just the AP® European History test.

You should also put X’s over the answer choices that you have eliminated while using the process of elimination. Doing so will help you to focus your attention on selecting the best possible answer choice. A word of warning: don’t cross out the entire selection. We’ve seen students waste several minutes trying to erase answers that they later realized might be correct.

Another helpful way to annotate multiple choice questions is by adding SOAP® annotations to the source line of each document.

This strategy is an excellent way of reminding yourself to contextualize the document before deep reading. Doing SOAP® annotations only takes a few seconds, but it will pay off in your multiple choice scores.

7. Use checkmarks.

If you feel confident about your answer to a particular multiple-choice question, make a small checkmark next to that question number. The reason why you want to do this is that when you go back to review your answer choices, you’ll be able to quickly recognize which questions you need to spend more time taking a second look at. Also, making this checkmark gives you momentum moving forward throughout the multiple-choice section. If you feel good about an answer, that little bit of positive reinforcement will help keep you alert as you move through the multiple choice questions.

8. Take advantage of chronology.

Unlike other AP® History exams, no one AP® European History unit is weighted more heavily than another, so we can’t accurately predict what topics will surely show up on the test. Still, when it comes to answering the multiple-choice questions, the questions are actually grouped in sets of 4-7 questions each.

Practice recognizing when you’re at the start and end of a group. This will allow you to mentally think about the different time periods that are being tested while also staying alert throughout the duration of the test.

9. Practice Using Albert.

If you want to get better at anything, you have to practice. We think the highest-quality practice available is through Albert.io. We offer tons of AP® European History practice exams, study modules, DBQ examples, and more. All of our materials are carefully curated and are aligned to what will actually show up on your test.

Return to the Table of Contents

AP® European History Free Response: 11 Tips

1. Turn the prompt into a question.

One of the most unfortunate mistakes that you can make during the free response section is to respond to a question that was not asked. It is absolutely essential that you understand the prompt before you start writing, and one of the very best ways to do so is to turn the prompt into a plain question that can be answered in one sentence.

For example, let’s investigate the 2019 AP® European History DBQ prompt, which was to “Evaluate whether or not the Catholic Church in the 1600s was opposed to new ideas in science.” How could you rewrite this?

We rewrote this prompt as the question: “In the 1600s, was the Catholic Church opposed to new ideas in science? If so, how strong was their opposition?”

2. Write your thesis…twice.

Once you have re-written the question, answer it twice: once in the introduction and once in the conclusion. Don’t use the exact same words. This test hack actually gives you a much stronger chance of earning the point for writing a thesis in both your DBQ and your LEQ. The 2019 Chief Reader Report notes that some responses have theses that are “more specific in the conclusion than in the introduction.” This means that students get the point for a thesis only after writing their entire essay.

Why do you think that is? We think it’s because many students gain an understanding of the prompt as they write, and by the conclusion, they are finally ready to produce a point-worth version.

We should also point out that both the 2018 and 2019 Chief Reader reports note that many “responses merely restated the prompt or did not indicate a line of reasoning.” It’s important to actually answer the question that you wrote in step one.

For example, the response “Some people wonder if the Catholic Church was actually opposed to scientific advancements in the 1600s, but others disagree” will not score you a thesis point. Why? You haven’t answered the question that you wrote! Take a side and be sure you back your response up with evidence.

3. Know the rubric like the back of your hand.

This goes in hand with the last tip. By the time the test rolls around, make sure you know that AP® graders are looking for these key components: an answer to all parts of the question, a clear thesis, facts to support the thesis presented, use of all documents, and inclusion of point of view/evaluation of document bias. Here is an awesome and very readable rubric that should help you to understand what exactly graders will be looking for in your writing.

It’s very difficult to get a perfect score on the AP® Euro DBQ. In 2019, the mean score on the AP® Euro was a 3.26 out of 7 possible points. The points that students miss most on the rubric are sourcing and complexity.

In order to get a better understanding of the rubric, we highly recommend that you read through the 2019 AP® European History DBQ Scoring Guidelines. This document provides ample examples of student writing that earn points in all categories.

4. Read the whole document.

One of the more common mistakes that students make each year on the DBQ is to quickly skim documents rather than reading them more closely. The 2019 Chief Reader Report noted that students “occasionally correctly analyzed one part but missed that the rest of the document contradicted that information.”

We know that you might feel rushed on time, but you can’t show off your ability to interpret and analyze documents if you don’t read them closely. Practice reading until the end of each document and check your understanding of that document by briefly summarizing it in writing before moving on.

5. Assess the author’s perspective.

As you work your way through the documents and group them, keep a few clear questions in mind, “Why is the author writing this? What perspective is he or she coming from? What can I tell from his or her background?” Asking yourself these questions will help you ensure part of your thesis and essay integrates bias and analysis of bias.

For example, Document 7 of the 2019 AP® European History DBQ was a, “Critique of French thinker René Descartes by the Jesuits of Clermont College.” An acceptable assessment of the author’s perspective would note that the Jesuits see Descartses’s model as undermining the Church’s authority.

6. Group, group, group, and did we say group?

When you read and analyze documents, make sure to group your documents into at least three groups in order to receive full credit. You should group based on the three respective key points you will be discussing in the body of your essay.

Just to hit the nail in the coffin, here are a few starting blocks for how to group documents. Think about how the document works in relation to politics, economics, imperialism, nationalism, humanitarianism, religion, society & culture, intellectual development & advancement. Pretty much every single document the CollegeBoard ever created can fit into one of these buckets.

7. Plan out your writing.

Writing a coherent essay is a difficult task. In order to do this successfully on the AP® European History test you want to make sure that you have spent a few minutes in the very beginning of the test to properly plan out an outline for your essay. You may have heard this advice hundreds of times from teachers but the reason why teachers give it is because it really does help. Ultimately, if you go into your essay without a plan your essay will read without a sense of flow and continuation. One of the things you are assessed on is your ability to create a cohesive argument.

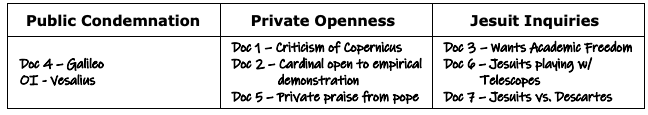

One specific tip for planning out your writing is to write down your groups and explicitly include them in your thesis statement. An excellent example of this comes from Tom Richey’s 2019 AP® Euro DBQ Sample Response.

Before writing, Mr. Richey splits the documents into three groups.

Only after brainstorming by grouping does he begin writing. Also notice how the work he does before writing directly influences the organization of his essay. For example, his thesis directly references all three groupings.

“Although Catholic leaders publicly condemned new ideas in science, some Catholic leaders were open to discussing these ideas in private and the intellectual Jesuits were often directly involved in experiments that confirmed new scientific discoveries.”

By planning his essay before writing it, Mr. Richey set himself up for success on the DBQ. His thesis is almost a copy of the brainstorm, and he has scored the thesis point. Additionally, each grouping becomes the main topic for his body paragraphs. You should notice that each topic sentence again directly references one grouping.

- “Catholic clergy were quick to publicly condemn discoveries that posed a threat to Catholic doctrine and traditional understandings of the Bible.“

- “While the Church was quick to publicly condemn scientific discoveries that threatened its doctrines, there were clergy that were open to discussing advances in science – especially in private.”

- “Eventually, the goals of the Jesuit Order to promote education would bring that order, and the Catholic Church as a whole, to embrace new ideas in science.”

Lastly, we should point out that Mr. Richey knows exactly where to use each document in the DBQ because he pre-planned his essay through grouping.

8. Use the contents of the document to answer the question.

This may seem obvious to you, but simply summarizing the documents is not going to earn you points on the DBQ. Instead, you should explain how the document is helpful in answering the question you wrote in Step One.

You will remember our question from Step One: “In the 1600s, was the Catholic Church opposed to new ideas in science? If so, how strong was their opposition?”

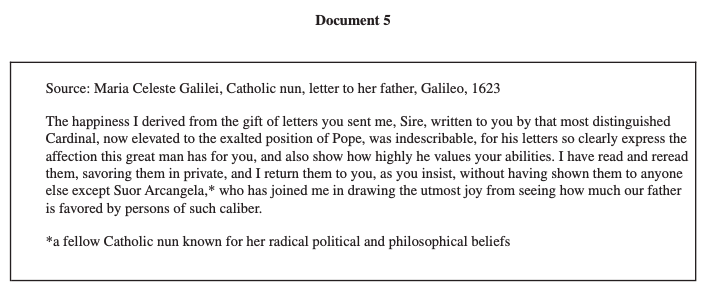

Now, imagine being given the following document:

How would you use this document in order to answer the question we wrote?

Do you think the following is an example of analysis, or is it simply summary?

“In this document, Maria Celeste Galilei writes a letter to her father explaining that the Pope values the abilities of her father, Galileo.”

If you said summary, you are correct. The sentence didn’t explain how the document was useful in answering the question.

Do you think the following is an example of analysis, or is it simply summary?

“Maria Celeste Galielei said, ‘Sire written to you by that most distinguished Cardinal, now elevated to the exalted position of Pope, was indescribable, for his letters so clearly express the affection this great man has for you, and also show how highly he values your abilities.’”

If you said summary, you are again correct. While this is a relevant quote, it’s not being used in any way to answer the question that we wrote back in step one.

Do you think the following is an example of analysis, or is it simply summary?

“Maria Celeste Galilei’s letter to her famous scientific father proves that some in the Church were open to the new ideas of science because the Pope himself had expressed an admiration of Galileo.”

If you said analysis, you are correct. The last sentence clearly responds to the initial question and explains the relevance of the document.

9. Connect between documents.

The difference between scoring a perfect score on your essays and scoring an almost perfect score can often come down to your ability to relate documents with one another. As you outline your essay, you should think about at least two opportunities where you can connect one document to another.

So how do you connect a document?

Well one way would be writing something along the lines of, “The fact that X person believes that XYZ is the root of XYZ may be due to the fact that he is Y.”

So in this example, weI may pull X person from document 1, but use document 4 to support my Y of the reason why he thinks a certain way. When you connect documents, you demonstrate to the grader that you can clearly understand point of views and how different perspectives arise. It also is a way to demonstrate your analytical abilities.

10. Do not blow off the DBQ.

If you are short on time, do not skimp on the DBQ. The DBQ is worth 25% of your grade, whereas the long essay is worth 15%. To be clear, both of these pieces of writing are valuable, but the DBQ is worth more.

Even if you feel stressed about the multiple choice section or the short answer response section, we’ve seen kids salvage their final score by writing a really strong DBQ.

11. Read some examples of strong DBQs.

If you’re not sure where to begin on DBQs, we often suggest reading a few sample DBQs. Check out this amazing annotated DBQ sample from the 2020 AP® European exam. You should be able to read student writing and be able to explain why it did or did not achieve a point.

One helpful way to improve your understanding of the DBQ rubric is to read a sample of student writing, create a prediction for if it scores a point, and then to cross reference your prediction against the actual score.

The College Board also freely offers sample responses here for many past exams. You can get a really good feel for these essays just by reading through a few samples.

Return to the Table of Contents

AP® European History Study Tips from Teachers

1. Keep referring back to the question.

While writing the essay portion, especially the DBQ, remember to keep referring back to the question and make sure that you have not gone off on a tangent. When students drop the ball on an essay it is usually because they do not answer the question. Thanks for the tip from Ms. N at South High School in MI.

2. Review your vocab.

Complete the vocabulary at the beginning of each section of your preferred AP® European History prep book. If you do not know the meaning of the terminology in a question you will not be able to answer the question correctly. Thanks for the tip from Ms. O at Northville High in MI.

Here’s a list of 35 Frequently Tested European History Terms & Concepts.

3. Do lots of point-of-view statements.

You don’t want to suffer on your DBQ because you only had two acceptable POV’s. Do 4 or 5 or 6. And be sure to say how reliable a source is ABOUT WHAT based on their background, audience or purpose. Thanks for the tip from Steve!

4. Complete readings as they are assigned.

Chunking material is the best way to learn and then to synthesize material. Look at the primary sources and secondary sources to support textual readings. Think in thematic terms. Thanks for the tip from Ms. J at Trinity High in PA.

5. Supplement your in-class learning with videos.

Tom Richey has put together a comprehensive YouTube playlist just for AP® European History students. You can check it out at here. He also has a great website you can check out here.

6. Provide context in your DBQ.

When trying to write a point of view statement for the DBQ you must include three things: First, state who the author really is. Second, what did he actually say. Third, why it said it.

Are you a teacher? Do you have an awesome tip? Let us know!

Hopefully you’ve learned a ton from reading all 50+ of these AP® European History tips. Remember, AP® European History is one of the most challenging AP® exams to score high on, so it’s crucial you put in the work to get you there. Read actively and review constantly throughout the year, so that you do not feel an incredible burden of stress as the AP® exam nears. Approach readings using SQ3R, connect the dots between documents, and understand how you are going to be graded by AP® readers. You’re going to do great! Good luck.

Return to the Table of Contents

Wrapping Things Up: The Ultimate List of AP® European History History Tips

The AP® European History Exam is one of the more challenging AP® tests, but you will do very well on it if you use the right strategies and work hard. You must not only build your content knowledge but also hone your writing skills and ability to think historically.

To begin preparing, create a regular study routing and stick to it. Use the test, study, test practice method using our AP® European History practice exams and questions broken down by topic. Create study groups and quiz each other using flashcards and Quizlet. Play European History timeline. Consistently studying with diverse methods is an excellent approach to ensuring success on the AP® European History exam.

- The one thing to remember about the AP® Euro Multiple-Choice Section: Read the source line closely before attempting to answer any question.

- The one thing to remember about the AP® Euro Free-Response Section: The better you understand the rubrics, the easier it will be to craft a strong essay.

- The key takeaway from teacher tips: Practice. Practice. Practice. The top students in this course will not only be productive in class but will spend many hours outside of class making sure their skills are honed before test day.

If you’ve made it this far, well done. You’re well on your way to success on the AP® European History exam. Work hard, use the study tips that you just learned, and do your very best on test day. Good luck!

9 thoughts on “The Ultimate List of AP® European History Tips”

Do lots of point-of-view statements: You don’t want to suffer on your DBQ because you only had two acceptable POV’s. Do 4 or 5 or 6. And be sure to say how reliable a source is ABOUT WHAT based on their background, audience or purpose.`

Love it, Steve!

DBQ – Nail the thesis! Once the docs are grouped be sure to follow the instructions…write a clear detailed and precise thesis that addresses all parts of the question.

We definitely agree, Keith! Answering the question (#1) and refining your thesis (#14) are crucial.

Thanks for this post and its good post.

You’re welcome!

Please continue to send…very helpful

Glad you enjoyed!

While some aspects of this were very useful, the full capacity of this list could have been better utilized if it wasn’t sent out so close to the exam. For example, several of the points stressed keeping up of your reading and material assignments, but for some, it’s a little to late to tell them that.

*EDIT: The tab to show me this list didn’t appear towards the end of the year, so if it were made known earlier, it would have been more useful.

Comments are closed.