Acing the AP® World History exam is undeniably a difficult task. Only 8.6% of students who took the 2019 exam scored a 5, and only 18.8% of students scored a 4. The test’s difficulty ultimately lies in how it forces you to analyze the overall patterns of history in addition to the small details.

By familiarizing yourself with trends in history as opposed to just memorizing facts, you can get a 5 on the AP® World History exam. The test can be cracked by understanding how history operates, how the world changes through cause and effect. Admittedly, it can be difficult to learn how to study for the AP® World History exam.

However, we’re here to help you score a 5 and formulate the perfect AP® World History study plan. Through practice and preparation, scoring a five is possible! By taking AP® World History practice tests, creating a thorough study plan, and maintaining a daily study routine, you will be able to ace this exam.

What We Review

Overall How To Study for AP® World History: 9 Tips for 4s and 5s

1. Answer ALL of the questions

Make sure your thesis addresses every single part of the question being asked for the AP® World History free-response section. Many times, AP® World History prompts are multifaceted and complex, asking you to engage with multiple aspects of a certain concept or historical era. Missing a single part can cost you significantly in the grading of your essay.

2. Lean one way in your argument

While it is possible to write essays that take two sides of an argument, it is always easier to choose a side and defend it. Trying to appease both sides during a timed essay often leads to an argument that’s not nearly as strong when you take a stance.

Here is an example of a weak thesis:

The recovery of Russia and China after the Mongols had many similarities and differences.

Here is a better one:

While both Russia and China built strong centralized governments after breaking free from the Mongols, Russia imitated the culture and technology of Europe while China became isolated and built upon its own foundations.

3. Lead your reader

Help your reader understand where you are going as you answer the prompt to the essay. Provide them with a map of a few of the key areas you are going to talk about in your essay. This should be done in your opening thesis paragraph. An easy way to achieve this is by outlining what is going to be discussed in your body paragraphs during the introduction paragraph.

4. Organize your essay with 2-3-1 in mind

When outlining the respective topics you will be discussing, start from the topic you know second best, then the topic you know least, before ending with your strongest topic area. In other words, make your roadmap 2-3-1 so that you leave your reader with the feeling that you have a strong understanding of the question being asked. This will help scaffold your argument, and it will make the essay much more readable.

5. Analyze rather than merely summarize

When the AP® exam asks you to analyze, you want to think about the respective parts of what is being asked and look at the way they interact with one another. This means that when you are performing your analysis on the AP® World History test, you want to make it very clear to your reader of what you are breaking down into its component parts.

For example, what evidence do you have to support a point of view? Who are the important historical figures or institutions involved? How are these structures organized? How does this relate back to the overall change or continuity observed in the world?

6. Use SPICER to organize and chunk your history reading

SPICER is a useful acronym that can be used to chunk and break down history into six different categories:

- S – Social

- P – Political

- I – Intellectual

- C – Culture

- E – Economic

- R – Religious

These six categories encompass the major areas of history that you will see in your reading and on your exam. Write an S next to material that deals with social issues, an E near economic, so on and so forth. This will break up your reading into more digestible chunks.

7. Familiarize yourself with the time limits

Part of the reason why we suggest practicing essays early on is so that you get so good at writing them that you understand exactly how much time you have left when you begin writing your second to the last paragraph. You’ll be so accustomed to writing under timed circumstances that you will have no worries in terms of finishing on time.

The multiple-choice section is 55 questions and 55 minutes long, so you have one minute per question. The short answer section is 3 questions and 40 minutes long; the document-based question is 1 question and timed at 1 hour. The long essay is 1 question and timed at 40 minutes.

8. Learn the rubric

If you have never looked at an AP® World History grading rubric before you enter the test, you are going in blind. You must know the rubric like the back of your hand so that you can ensure you tackle all the points the grader is looking for. Here are the 2019 Scoring Guidelines.

While all the rubrics for the DBSs vary a bit, they mostly follow a 0-3 scale where each number represents a certain task you must fulfill within your response. The DBQ section is graded on a four-scale basis:

- A) Thesis/Claim

- B) Contextualization

- C) Evidence

- D) Analysis and Reasoning

The thesis component evaluates the strength of your thesis statement, while the contextualization section evaluates your ability to describe a broader historical context relevant to the prompt. The evidence part of the rubric evaluates your analysis and use of the texts, and the analysis and reasoning section evaluates your argument overall.

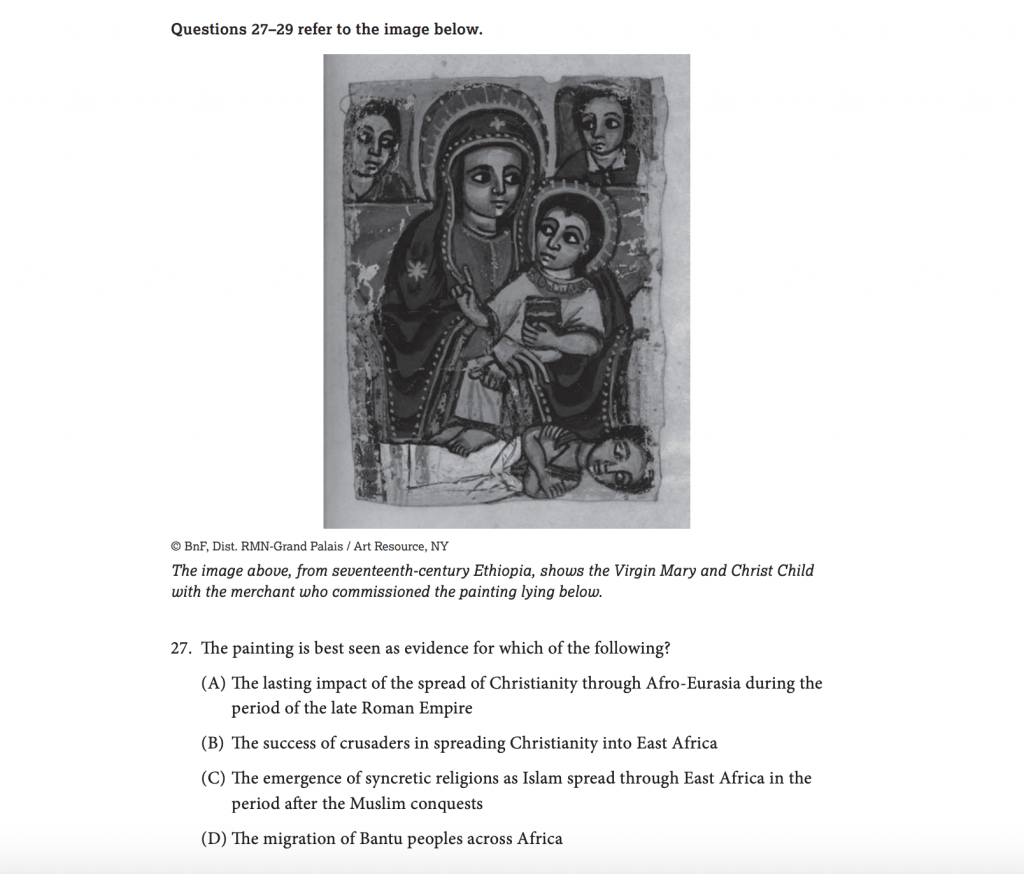

9. Familiarize yourself with analyses of art

This one is optional, but a great way to really get used to analyzing art is to visit an art museum and to listen to the way that art is described. Oftentimes the test will make you either interpret the artist’s intent and perspective or force you to expound on history through interpretation of the painting.

Here’s an example.

Notice how the painting is being used to assess an entire historical era. The painting is being used here as much more than a painting.

Return to the Table of Contents

Return to the Table of Contents

AP® World History Multiple Choice Review: 11 Tips

1. Identify key patterns of history

You know that saying, history repeats itself? There’s a reason why people say that, and that is because there are fundamental patterns in history that can be understood and identified. This is especially true with AP® World History.

Think about patterns like cause and effect, action and reaction, dissemination and reception, oppressor vs. oppressed, etc. History can be best comprehended when you recognize patterns.

2. Use common sense

The beauty of AP® World History is when you understand the core concept being tested and the patterns in history; you can deduce the answer to the question. Identify what exactly is being asked and then go through the process of elimination to figure out the correct answer.

Now, this does not mean you do not study at all. This means, rather than study 500 random facts about world history, really hone in on understanding the way history interacts with different parts of the world.

Think about how minorities have changed over the course of history, their roles in society, etc. You want to look at things at the big picture so that you can have a strong grasp of each time period tested.

3. Familiarize yourself with AP® World History multiple-choice questions

If AP® World History is the first AP® test you’ve ever taken, or even if it isn’t, you need to get used to the way the College Board introduces and asks you questions. Find a review source to practice AP® World History questions.

Albert has hundreds of AP® World History practice questions and detailed explanations to work through. These questions are designed to encompass tons of years of World History, so you must become acquainted with how that history is presented to you.

4. Make a note of pain points

As you practice, you’ll quickly realize what you know really well, and what you know not so well. Figure out what you do not know so well and re-read that chapter of your textbook. Keep a chart or log of what you do not do quite so well, so when it comes time to review, you can quickly discern which area you need to study. Then, create flashcards of the key concepts of that chapter along with key events from that time period.

5. Supplement practice with video lectures

A fast way to learn is to do practice problems, identify where you are struggling, learn that concept more intently, and then practice again. Crash Course has created an incredibly insightful series of World History videos you can watch on YouTube here. And Useful Charts offers tons of great timeline-oriented videos on plenty of subjects including world history.

Afterward, go back and practice again. Practice makes perfect, especially when it comes to AP® World History. And a lot of these videos are actually pretty interesting.

6. Strikeout wrong answer choices

The second you can eliminate an answer choice, strike out the letter of that answer choice and circle the word or phrase behind why that answer choice is incorrect. This way, when you review your answers at the very end, you can quickly check through all of your answers.

One of the hardest things is managing time when you’re doing your second run-through to check your answers—this method alleviates that problem by reducing the amount of time it takes for you to remember why you thought a certain answer choice was wrong.

7. Answer every question

If you’re crunched on time and still have several AP® World History multiple-choice questions to answer, the best thing to do is to make sure that you answer each and every one of them. There is no guessing penalty for doing so, so take full advantage of this!

8. Skip questions holding you up and return to them later

If you find yourself spending more than a minute or so on a question, don’t let yourself get stuck. Instead, circle the number of the question, skip it, and return to it later if you have time. Since this is a timed component of the exam (55 minutes), the pacing is essential to scoring high. If you find yourself getting stuck, don’t fixate. Circle then move on and return.

9. Don’t be afraid to make educated guesses

This one dovetails nicely with the preceding tip. If you find yourself totally at a loss choosing an answer on the AP® World History multiple-choice section, make an educated guess. You are not penalized for answers you miss; your scores are counted by how many you get right. So it’s in your benefit to answer every question and leave none blank. So, when confronted with impossibly difficult questions, try and narrow the choices down a bit and then just make an educated guess.

10. Keep your eyes peeled for corresponding questions that provide answers

Sometimes, in multiple-choice exams, questions can actually sort of answer each other. For example, say question 12 depicts a painting of the 1789 Storming of the Bastille, and question 30 asks you to describe the mood of the late-eighteenth century France, you can use question 12 to help you answer question 30. Since many of the events in AP® World History correspond, you will likely see instances of this. Use it to your advantage.

11. Form a study group

Developing a strong memory of historical dates, events, figures, and all the stuff essential to AP® World History is crucial to acing the multiple-choice component of the exam. One way to build your memory is to form a study group with your classmates and meet weekly or bi-weekly. Before you meet, plan out which parts of world history you want to cover, and stick to it. Choose your group wisely because sometimes, study groups can quickly turn into hang-out sessions.

Return to the Table of Contents

AP® World History FRQ: 17 Tips

1. Group the documents by intent

One skill tested on the AP® exam is your ability to relate documents to one another–this is called grouping. The idea of grouping is to essentially create a nice mixture of supporting materials to bolster a thesis that addresses the DBQ question being asked. In order to group effectively, create at least three different groupings with two subgroups each.

When you group, group to respond to the prompt. Do not group just to bundle certain documents together. The best analogy would be you have a few different colored buckets, and you want to put a label over each bucket. Then you have a variety of different colored balls in which each color represents a document, and you want to put these balls into buckets. You can have documents that fall into more than one group, but the big picture tip to remember is to group in response to the prompt.

This is an absolute must. 33% of your DBQ grade comes from assessing your ability to group.

2. Assess POV with SOAPSTONE

SOAPSTONE helps you answer the question of why the person in the document made the piece of information at that time. Remember that SOAPSTONE is an acronym:

- S – Speaker

- O – Occasion

- A – Audience

- P – Purpose

- S -Subject

- Tone – Tone

It answers the question of the motive behind the document and can help you engage with the documents more effectively.

3. S represents Speaker or Source

You want to begin by asking yourself who is the source of the document. Think about the background of this source. Where do they come from? What do they do? Are they male or female? What are their respective views on religion or philosophy? How old are they? Are they wealthy? Poor? Etc. Understanding the source of the text will help unlock its nature, and it will allow you to approach the reading with a specific angle in mind.

4. O stands for occasion

You want to ask yourself when the document was said, where was it said, and why it may have been created. You can also think of O as representative of origin. Analyzing the occasion or origin of a historical text will provide you with much-needed context, which is essential to decoding history. When you confront a text, immediately ask yourself what the occasion of the text is.

5. A represents audience

Think about who this person wanted to share this document with. What medium was the document originally delivered in? Is it delivered through an official document, or is it an artistic piece like a painting? The intention behind a piece is crucial to understanding its meaning. If you can figure out who the text was intended for, then you can begin to unpack what it is all about. The audience is crucial.

6. P stands for the purpose

After you’ve asked who the audience of the text is, begin asking, “why?” Think, “why did this person create this document?” or “why did they say this or that?” What is the main motive behind the document? Obviously, unpacking the purpose of a text is essential to understanding it as a whole, and, again, it serves as an essential step in the process of breaking down the text.

7. S is for the subject of the document.

Next is the subject. Every text addresses a broader or larger subject either implicitly or directly, and understanding this will help chunk your reading and make your writing more sophisticated. For instance, the Silk Road is a trading route, sure, but it is also more broadly about the rise of globalism and international relationships. WWI is, of course, a catastrophic war, but it’s also about the rise of technology, international discord, humanitarianism, and even masculinity. When you read a historical text, think, “what is this really about?”

8. TONE poses the question of what the tone of the document is.

This relates closely to the speaker. The tone is a general character or attitude of a place, piece of writing, or a situation. Writers create tone through a variety of ways but pay special attention to strong vocabulary words, key phrases, literary or rhetorical devices, mood words, and more elements of writing that generate the tone. Highlight or underline them. Think about how the creator of the document says certain things. Think about the connotations of certain words.

9. Explicitly state your analysis of POV

Your reader is not psychic. He or she cannot simply read your mind and understand exactly why you are rewriting a quotation by a person from a document. Be sure to explicitly state something along the lines of, “In document X, author states, “[quotation]”; the author may use this [x] tone because he wants to signify [y].” Another example would be, “The speaker’s belief that [speaker’s opinion] is made clear from his usage of particularly negative words such as [xyz].”

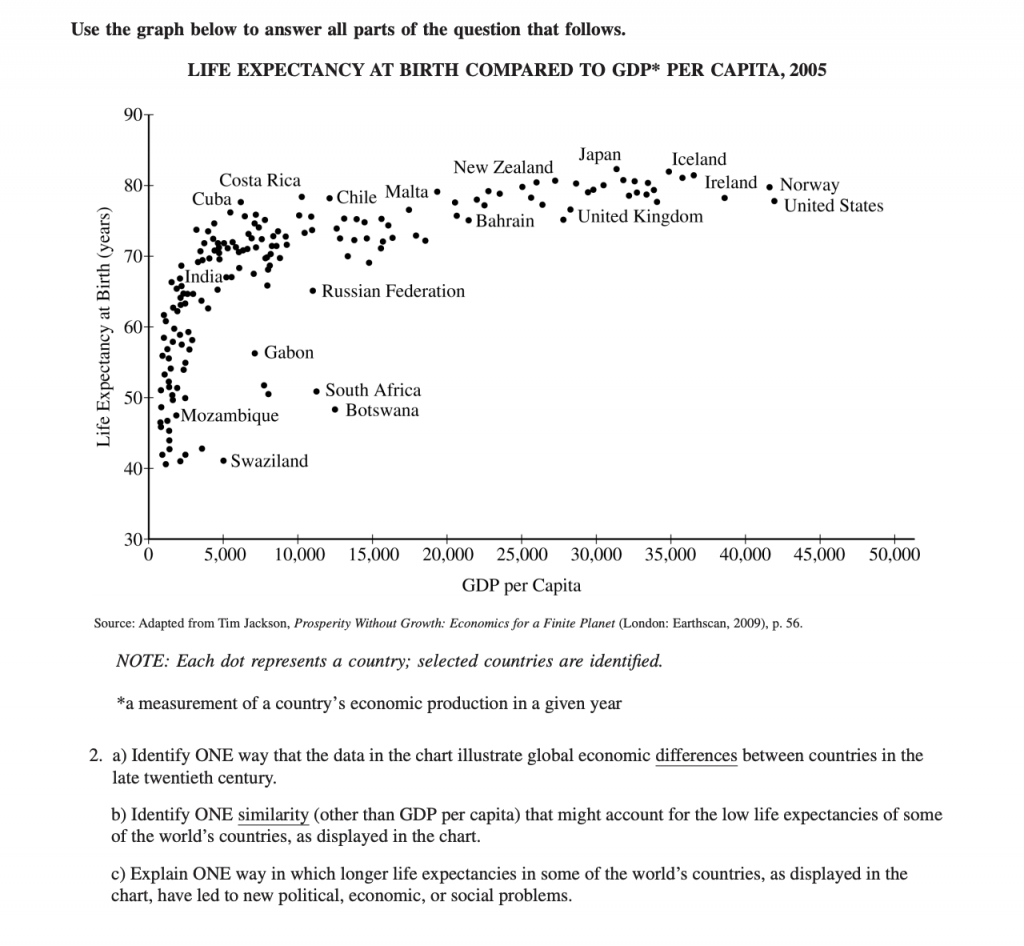

10. Be conscious of how you use data from charts and tables

Sometimes you’ll come across charts of statistics. If you do, ask yourself questions like where the data is coming from, how the data was collected, who released the data, etc. You essentially want to take a similar approach to SOAPSTONE with charts and tables. Data should be analyzed rather than merely summarized.

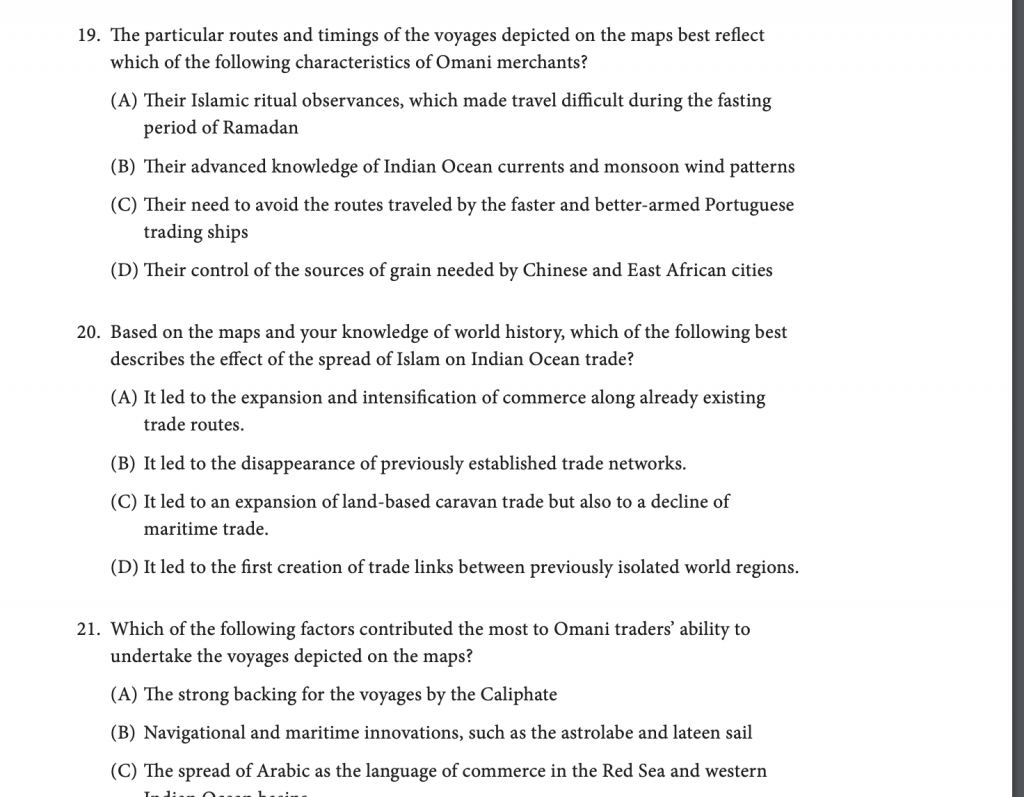

Notice how the prompt asks you to either “identify” or “explain.” If you choose to answer one of the questions with “identify,” you must go much further than simply identifying. You must move into the realm of “explain” and “analyze.”

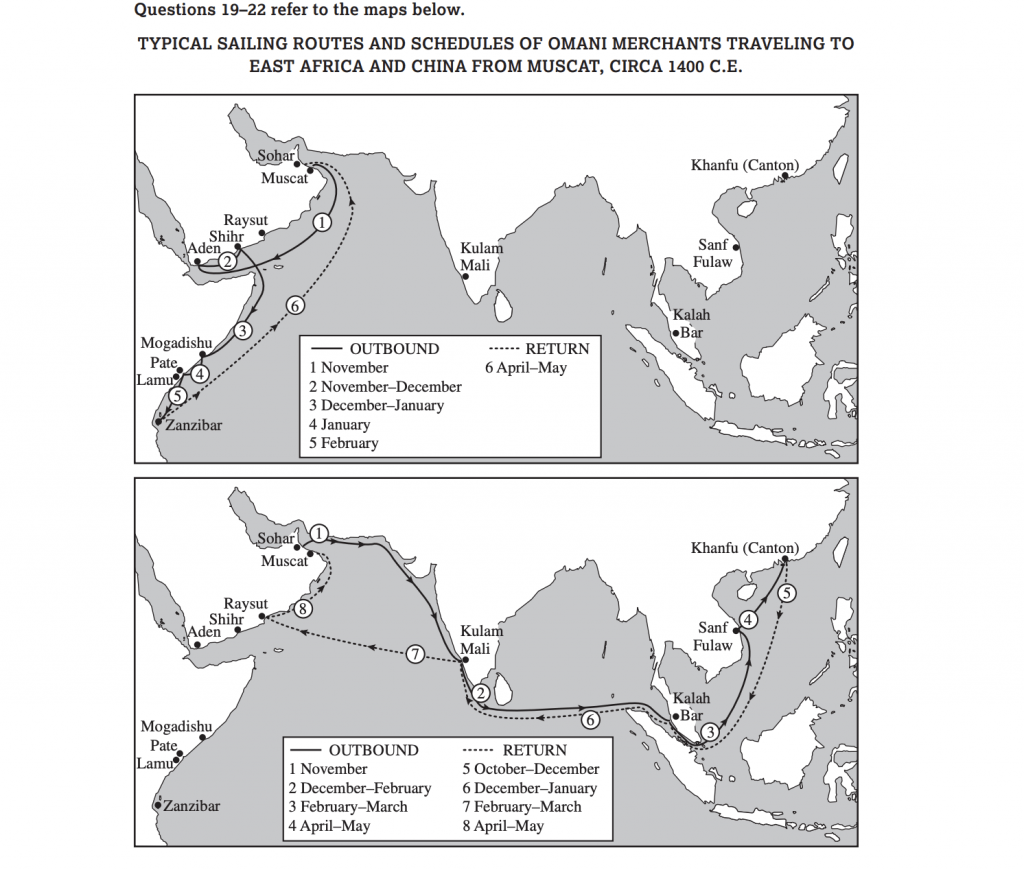

11. Assess maps with a strategy in mind

When you come across maps, look at the corners and center of the map. Think about why the map may be oriented in a certain way. Think about if the title of the map or the legend reveals anything about the culture the map originates from. Think about how the map was created–where did the information for the map come from. Think about who the map was intended for.

12. Assess cultural pieces with SOAPSTONE in mind

If you come across more artistic documents such as literature, songs, editorials, or advertisements, you want to really think about the motive of why the piece of art or creative writing was made and who the document was intended for. What does that specific piece tell you about the time in which it was created?

13. Be careful using blanket statements

Just because a certain point of view is expressed in a document does not mean that POV applies to everyone from that historical area. One common problem students make is expressing one sentiment for a large group of people, events, or historical eras. Be aware that history can rarely be reduced to X = Y. A grey area persists. One easy way to avoid this pitfall is to be as specific as possible. Take a look at these examples from the 2019 exam:

Blanket statement: “During 1450 to 1750 the creation of the Mongol Empire changed the role of nomads in cultural exchange. Before the Mongols, nomads acted as traders who spread trade and culture along routes, but this changed during the Mongol Empire, nomads became the protectors who patrolled the trade routes to keep them safe.”

Notice how the writer paints nomadic tribes with too wide of a wide brush and does not discuss their trade with enough specificity.

Now here’s a more specific example:

“One development that changed the role that Central Asian Nomads played in cross-regional exchanges from the period 1450– 1750 C.E., as described in the passage, was the development of maritime technology because new modes of transportation across the ocean using boats and knowledge of monsoon winds allowed countries to trade and exchange ideas and goods across regions with less overland use, which diminished the importance of central Asian nomads in exchanging goods and ideas and cultures overland. An example of this includes European maritime empires such as Britain and Portugal, who navigated to Asia on sea in order to trade at trading posts. This sufficiently decreased central Asian nomads’ need to exchange goods along the Silk Road from Europe to Asia.”

Source: Chief Reader Report

Notice how specific the writer is when discussing the nomads’ trading.

14. Understand that bias will always exist

Even if you’re given data in the form of a table, there is bias in the data. Do not fall into the trap of thinking just because there are numbers it means the numbers are foolproof. Bias can and should be withdrawn from any and all sources.

Here’s an example of a bias historical statement: The Russian Revolution was initiated by an angry lower-class looking for revenge against a greedy ruling class.

While this may be somewhat true, notice how the words “angry” and “greedy” indicate particular moods toward these subjects from the author.

Instead, the statement should be written as “The Russian Revolution was initiated by Russia’s lower class against the ruling monarchy.

15. Be creative with introducing bias

Many students understand that they need to show their understanding that documents can be biased, but they go about it the wrong way. Rather than outright stating, “The document is biased because [x],” try, “In document A, the author is clearly influenced by [y] as he states, “[quotation].” See the difference? It’s subtle but makes a clear difference in how you demonstrate your understanding of bias.

16. Don’t forget to B.S. in your DBQ

No, no. It’s not what you’re thinking. By B.S., we mean to be specific. When you are discussing a certain revolutionary leader, an economic policy, a governmental act, or some other different aspect of AP® World History, be sure to specifically name your topics. Do not just generalize, but B.S.!

Here’s an example of a general statement: “While both sides fought the Civil War over the issue of slavery, the North fought for moral reasons while the South fought to preserve its own institutions.”

And here’s one that’s more specific: “While both Northerners and Southerners believed they fought against tyranny and oppression, Northerners focused on the oppression of slaves while Southerners defended their own right to self-government.”

17. Leave yourself out of it

Do not refer to yourself when writing your DBQ essays! “I” has no place in these AP® essays. Academic essays need to remain professional and focused, and the introduction of “I” detracts from that tone. And the reader already knows that your essay is written from your perspective, so an “I” is just redundant.

Return to the Table of Contents

Tips Submitted by AP® World History Teachers

Overall AP® World History Tips

1. Use high polymer erasers

When answering the multiple-choice scantron portion of the AP® World History test, use a high polymer eraser. It is the only eraser that will fully erase on a scantron. Amazon carries plenty for cheap. Thanks for the tip from Ms. J. at Boulder High School.

2. Stay ahead of your reading and when in doubt, read again

You are responsible for a huge amount of information when it comes to tackling AP® World History, so make sure you are responsible for some of it. Create a daily reading habit where you spend at least an hour per day digesting your AP® World History material. There is simply too much for you to try and cram. And you can’t leave all the work up to your instructor. It’s a team effort. Thanks for the tip from Mr. E at Tri-Central High.

3. Integrate video learning

A great way to really solidify your understanding of a concept is to watch supplementary videos on the topic. Crash Course offers a lot of great video content on World History, and Heimler’s History does as well. Then, after watching a video, read the topic again to truly master it. Thanks for the tip from Mr. D at Royal High School.

4. Practice with transparencies or a whiteboard

Use transparencies or a whiteboard to create overlay maps for each of the six periods of AP® World History at the start of each period so that you can see a visual of the regions of the world being focused on. History is perfect for big whiteboards because they allow you to draw out large maps, event chains, and more. Thanks for the tip from Ms. W at Riverbend High.

AP® World History Multiple-Choice Tips

1. Read every word

Oftentimes in AP® World History, many questions can be answered without specific historical knowledge. Many questions require critical thinking and attention to detail; the difference between a correct answer and an incorrect answer lies in just one or two words in the question or the answer. Be aware of answer choices like “none of the above” or “all of the above,” as either none or all of the questions must be correct or incorrect. Keep that totality in mind. Thanks for the tip from Mr. R. at Mandarin High.

2. Look at every answer option

Don’t go for the first “correct” answer; find the most “bulletproof” answer. The one you’d best be able to defend in a debate. Think of the “bulletproof” answer as an answer which can be tested and tested and tested but still holds up. Run this through your head while choosing an answer, and constantly reevaluate.

3. Annotate the text

Textbook reading is essential for success in AP® World History, but learn to annotate smarter, not harder. Be efficient in your reading and note-taking. Read, reduce, and reflect. To read – use sticky notes. Using post-its is a lifesaver – use different color stickies for different tasks (pink – summary, blue – questions, green – reflection, etc.) Reduce – go back and look at your sticky notes and see what you can reduce – decide what is truly essential material to know or question. Then reflect – why are the remaining sticky notes important? How will they help you not just understand the content, but also understand contextualization or causality or change over time? What does this information show you? Thanks for the tip from Ms. J at Legacy High.

AP® World History FRQ Tips

1. Master writing a good thesis

In order to write a good thesis, you want to make sure it properly addresses the whole question or prompt, effectively takes a position on the main topic, includes relevant historical context, and organize key standpoints. Heimler’s History has a good how-to guide on AP® World History thesis statements that’s certainly worth checking out. Thanks for the tip from Mr. G at Loganville High.

2. Tackle DBQs with SAD and BAD

With the DBQ, think about the Summary, Author, and Date & Context. Also, consider the Bias and Additional Documents to verify the bias. Thanks for the tip from Mr. G at WHS.

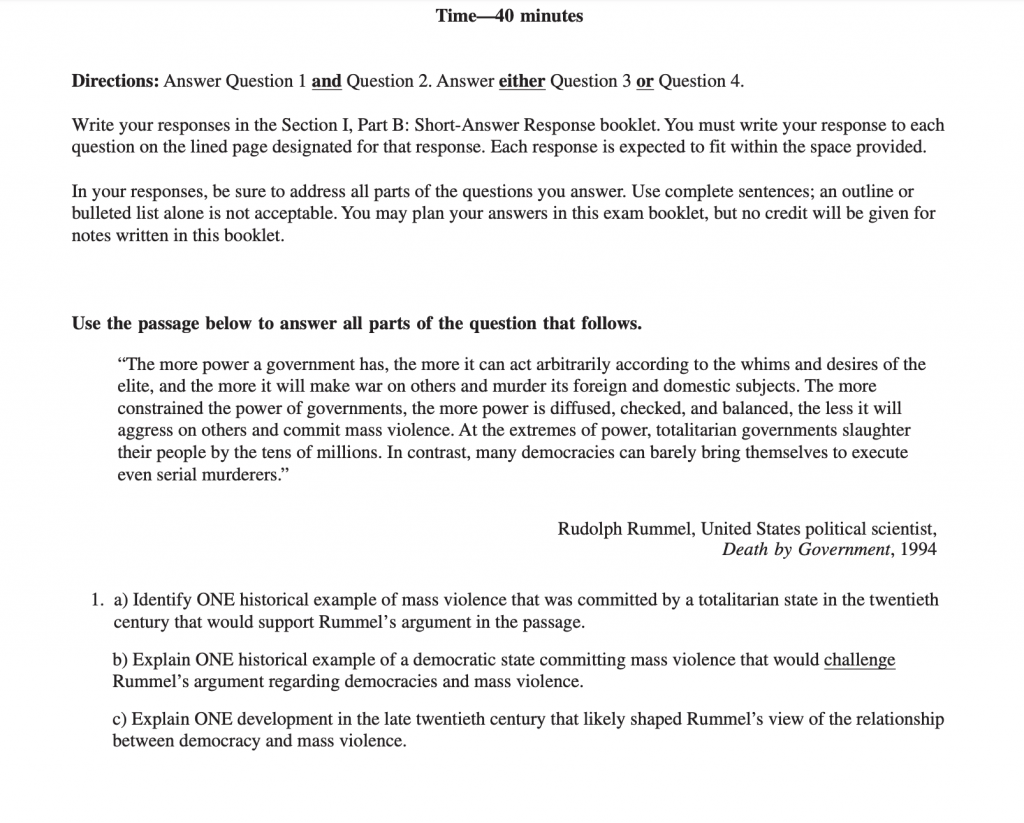

Go through this prompt from the 2019 exam and notice how SAD and BAD work well. It is about totalitarian governments by Rudolph Rummel, a US political scientist, from 1994. Does it present any bias? Additional documents? SAD and BAD can.

3. Create a refined thesis in your conclusion

Do not simply blow off your conclusion paragraph. Think of the conclusion as the decorative bow that nicely holds the box together. By the time you finish your essay, you have a much more clear idea of how to answer the question. Take a minute and revisit the prompt and try to provide a much more explicit and comprehensive thesis than the one you provided in the beginning as your conclusion. This thesis statement is much more likely to give you the point for the thesis than the rushed thesis in the beginning. Thanks for the tip from Mr. R at Mission Hills High.

4. Relate back to the themes

Understanding 10,000 years of world history is hard. Knowing all the facts is darn near impossible. If you can use your facts/material and explain it within the context of one of the APWH themes, it makes it easier to process, understand, and apply. The themes are your friends. Thanks for the tip from Ms. J at Legacy High.

5. Look for the missing voice in DBQs

First, look for the missing voice. Who haven’t you heard from in the DBQ? Who’s voice would really help you answer the question more completely? Next, if there isn’t really a missing voice, what evidence do you have access to, that you would like to clarify? For example, if you have a document that says excessive taxation led to the fall of the Roman Empire, what other pieces of information would you like to have access to that would help you prove or disprove this statement? Maybe a chart that shows tax amounts from prior to the 3rd Century Crisis to the mid of the 3rd-century crisis? Thanks for the tip from Ms. J at Legacy High.

Return to the Table of Contents

Wrapping Things Up: The Ultimate List of AP® World History Tips

Doing well in AP® World History comes down to recognizing patterns and trends in history, and familiarizing yourself with the nature of the test. Students often think the key to AP® history tests is memorizing every single fact of history, and the truth is you may be able to do that and get a 5, but the smart way of doing well on the test comes from understanding the reason why we study history in the first place.

By learning the underlying patterns that are tested on the exam, for example, how opinions towards women may have influenced the social or political landscape of the world during a certain time period, you can create more compelling theses and demonstrate to AP® readers a clear understanding of the bigger picture.

The bottom line is this: in order to ace this exam, you have to prepare. We offer tons of AP® World History practice questions, practice exams, AP® World History DBQs, and more. We recommend that you take a look at our extensive catalog, and develop a daily study routine. With this proper preparation, you will ace the exam!

12 thoughts on “The Ultimate List of AP® World History Tips”

When writing the DBQ, do not waste time quoting the documents; paraphrase and show the grader you understand what it’s saying.

Excellent tip, Rebecca!

Good tips for AP® World History.

Glad you enjoyed!

Thanks to AP® World History Teachers for these great tips.. keep it up.

Yes, they’re great!

An additional tip is to bring your own watch to the exam so that you can easily keep track of time.

Thanks for the addition!

My teacher submitted the first tip from teachers on high polymer erasers, and she is right. I only ever use these eraser for erasing anything in school and they work much better and last much longer than the stubby pink things on the end of pencils that people like to call “erasers.”

Thanks for sharing!

An extra tip is to convey your own particular watch to the exam so you can without much of a stretch monitor time.

Awesome!

Comments are closed.