Calculating the derivative of cos(x) is one of the most important questions in single variable calculus, because the derivatives of other trigonometric functions can be derived from the derivative of cos(x) using differentiation rules. In this calculus review, we investigate the properties of the function cos(x) and how to differentiate it. We also demonstrate how that derivative can be derived from the derivative of sin(x). This post answers all your questions about the derivative of cos(x).

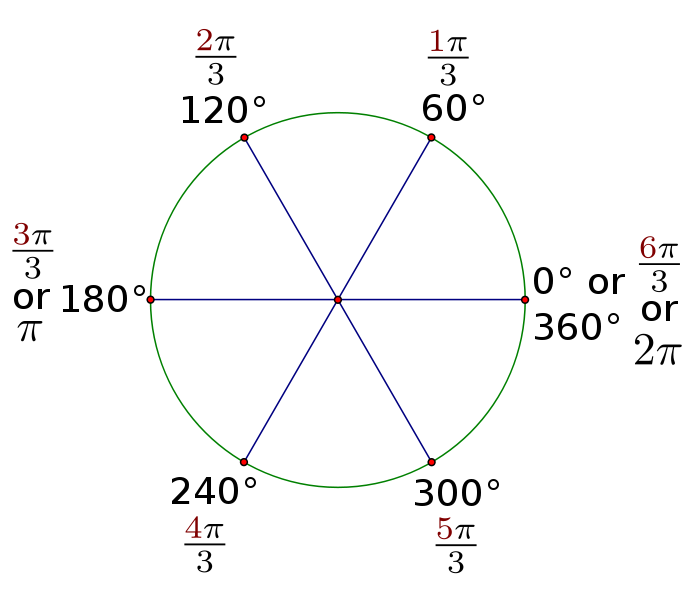

In calculus, angles are most conveniently measured in radians instead of degrees. An angle x in radians is defined as the length of an arc of the unit circle (with a radius of one). Since a circle with radius one has a circumference of 2 \pi , we can express x as follows:

x = \dfrac{2\pi}{360, \text{degrees}}, \theta

where \theta is the same angle in degrees. The conversion from radians to degrees is illustrated on the image below:

Now consider the function

f(x) = cos (x)

We will now apply the methods of single variable calculus to investigate the derivative of cos(x) and prove that

\dfrac{d}{dx}, cos(x) = -, sin (x)

Deriving the Derivative from a Fundamental Definition

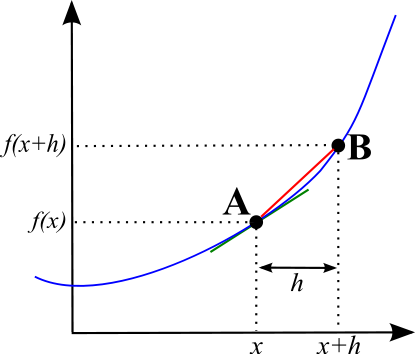

The image below demonstrates the process of finding the derivative of a function f(x) based on the definition of the derivative:

A and B are two points that are very close together on the curve y = f(x) . As the difference h between the x-coordinates of the points A and B becomes smaller, the chord AB (red line) approaches a tangent at A (green line). By definition, the derivative of the function f(x) is a limit:

f'(x) =\dfrac{d}{d x},f(x) = \lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{ f(x+h) - f(x) }{h}

Applying this general rule to the function f(x) = cos (x) , we get

\dfrac{d}{d x}, cos(x) = \lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{cos ( x + h ) - cos x}{h}

We can proceed further by using a trigonometric identity for the cosine of the sum of two angles:

cos (x + h) = cos(x) cos(h) - sin(x) sin(h)

This results in the following:

\dfrac{d}{d x}, cos(x) = \lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{ cos(x) cos(h) - sin(x) sin(h) - cos(x)}{h}

Collecting the variables, we can rewrite this in the form

\dfrac{d}{d x}, cos(x) = cos (x) \left[ \lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{ cos (h) - 1 }{h} \right]- sin (x) \left[ \lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{sin (h) }{h} \right]

Now, we transform the expression cos (h) - 1 via the double-angle formula:

cos (h) = cos^2 \left( \dfrac{h}{2} \right) - sin^2 \left( \dfrac{h}{2} \right) = 1 - 2 sin^2 \left( \dfrac{h}{2} \right)

So, we have

cos (h) - 1 = - 2 sin^2 \left( \dfrac{h}{2} \right)

Thus, the following equality holds:

\dfrac{d}{d x}, cos(x) = - ,cos (x) \left[ \lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{sin^2 \left( \dfrac{h}{2} \right) }{ \dfrac{h}{2} } \right]- ,sin x \left[ \lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{sin (h) }{h} \right]

To evaluate the limits presented here, let’s look at the geometric representation of the basic trigonometric functions in terms of a unit circle:

As we can see from this image, if an angle is measured in radians (remember that the angle x in this case equals the length of an arc on the unit circle), the following inequality holds:

sin (x) < x < tan (x)

Dividing this inequality by sin (x) , we get

1 < \dfrac{x}{sin (x)} < \dfrac{1}{cos (x)}

or, equivalently:

cos (x) < \dfrac{sin (x)}{x} < 1

But as x tends to zero, cos x evidently tends to unity, i.e. the function sin (x) / x always lies between unity and a magnitude tending to unity. Hence,

,\lim\limits_{x \rightarrow 0},\dfrac{ sin (x)}{ x } = 1

Consequently:

,\lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0},\dfrac{ sin (h)}{ h } = 1

And:

\lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0},\dfrac{sin^2 \left( \dfrac{h}{2} \right) }{\dfrac{h}{2}} = \lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0} , sin \left(\dfrac{h}{2} \right) = 0

Finally, we have:

\dfrac{d}{d x}, cos(x) = - ,cos x \left[ \lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{sin^2 \left( \dfrac{h}{2} \right) }{\dfrac{h}{2}} \right]- sin x \left[ \lim\limits_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{sin (h) }{h} \right] =-,cos (x) \cdot 0 - sin (x) \cdot 1 = - sin (x)

This is the desired result for the derivative of cos(x).

Proof Based on the Derivative of Sin(x)

In single variable calculus, derivatives of all trigonometric functions can be derived from the derivative of cos(x) using the rules of differentiation.

Equivalently, we can prove the derivative of cos(x) from the derivative of sin(x). Let’s see how this can be done.

We know the derivative of sin(x) is defined by the following expression:

\dfrac{d}{d x},sin (x) = cos (x)

We also know that when trigonometric functions are shifted by an angle of 90 degrees (which is equal to \pi/2 in radians), the following identity holds:

cos \left( \dfrac{\pi}{2} - y \right) = sin (y)

Differentiating the left hand side of this identity, we obtain

\dfrac{d}{d y},cos \left( \dfrac{\pi}{2} - y \right) = \dfrac{d x}{d y} \cdot \dfrac{d}{d x},cos (x)

Where x is a new variable, defined as

x = \dfrac{\pi}{2} - y

Obviously,

\dfrac{d x}{d y} = - 1

So we have

\dfrac{d}{d y},cos \left( \dfrac{\pi}{2} - y \right) = -, \dfrac{d}{d x} ,cos (x)

On the other hand, based on the trigonometric identity from above, we can write

\dfrac{d}{d y},cos \left( \dfrac{\pi}{2} - y \right) = \dfrac{d}{d y} ,sin (y) = cos (y)

where we have also used the law of differentiation for sin(x).

Thus, we have

\dfrac{d}{d x},cos (x) = -,cos (y) = -, cos \left( \dfrac{\pi}{2} - x \right) = -,sin (x)

Naturally, both methods that we have presented for the proof of the derivative of cos(x) give the same result.

Wrapping Up the Derivative of Cos(x)

In this calculus review article, we have investigated different ways to prove the derivative of cos(x). Now, you will be able to prove the derivative of cos(x) by using fundamental definitions or the derivative of sin(x). We hope this post gives you greater confidence in your knowledge of differentiation rules and facilitates your studies of single variable calculus.

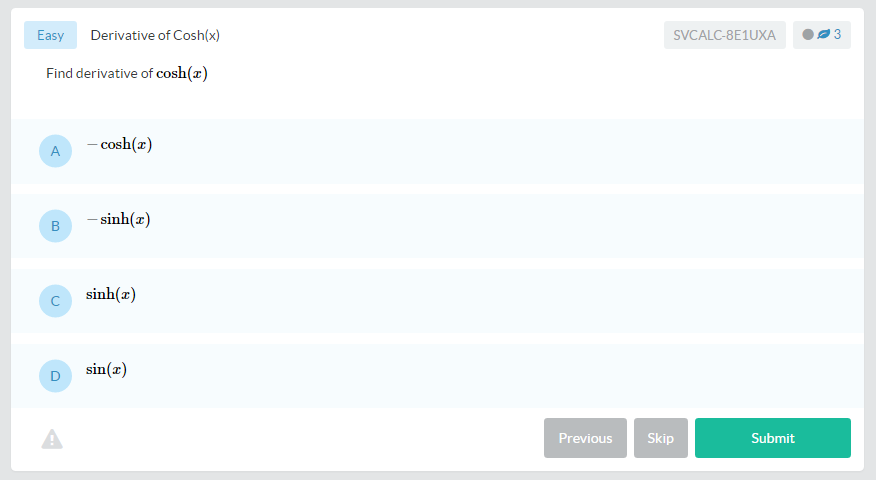

Let’s put everything into practice. Try this Single Variable Calculus practice question:

Looking for more Single Variable Calculus practice?

You can find thousands of practice questions on Albert.io. Albert.io lets you customize your learning experience to target practice where you need the most help. We’ll give you challenging practice questions to help you achieve mastery in Single Variable Calculus.

Start practicing here.

Are you a teacher or administrator interested in boosting Single Variable Calculus student outcomes?

Learn more about our school licenses here.