Temperature and heat affect our lives on a daily basis. From deciding what to wear to cooking to complicated air conditioning systems to global warming, we can see the real-world applications of temperature and heat. While both terms are used interchangeably, they have two different meanings. In AP® Chemistry, they are part of the thermochemistry topic. In simple terms, heat is the energy transferred from a hotter body to a cooler one, while the temperature is the degree of hotness or coldness of a substance. This discussion will cover the differences between temperature and heat, which includes the technical definitions of both terms, ways to measure temperature and heat, commonly used units of measurement, and how they are related to each other. This AP® Chemistry review also covers some common calculations related to temperature and heat.

Temperature

Temperature, in AP® Chemistry, is defined as the measure of the motion of particles in a substance. It is the average kinetic energy of random motion of electrons, atoms, and molecules that move freely within the substance. Temperature is an intensive variable, meaning its measurement does not depend on the amount of material in an object.

Measuring Temperature

Temperature is measured with a variety of instruments. The most common is with a mercury-filled thermometer. Mercury volume changes with a change in temperature. Other temperature-measuring devices, mainly in manufacturing plants, are thermocouples, infrared radiators, and resistive temperature devices.

Notation and Units

In AP® Chemistry, temperature is one of the seven SI base units. Temperature uses the symbol T and the unit Kelvin (\text{K}), which is the absolute temperature scale. This scale is named after Lord Kelvin, who defined this absolute scale. In Kelvin, 0 \text{ K} corresponds to the temperature at which motion ceases to exist. The Celsius and Fahrenheit scales are two other common temperature measurements. The Celsius scale is the most common temperature scale used worldwide, whereas Fahrenheit is commonly known as the American unit for temperature. For comparison, the table below shows the freezing and boiling points of water in different scales.

Table 1. Freezing and Boiling Points of Water in Different Temperature Scale

| Unit | Freezing Point of Water | Boiling Point of Water |

| Kelvin (\text{K}) | 273 | 373 |

| Celsius (^\circ \text{C}) | 0 | 100 |

| Fahrenheit (^\circ \text{F}) | 32 | 212 |

The following equations are useful in reviewing AP® Chemistry. They convert a measurement from one temperature scale to another.

{ T }_{ \left( { ^{\circ}\text{F} } \right) }=\dfrac { 9 }{ 5 } { T }_{ \left( ^{\circ}\text{C} \right) }+32

{ T }_{ \left( { ^{\circ}\text{C} } \right) }=\dfrac { 5 }{ 9 } { T }_{ \left( ^{\circ}\text{F} \right) }-32

{ T }_{ \left( \text{K} \right) }=273+{ T }_{ \left( ^{\circ}\text{C} \right) }

Heat

Unlike temperature, heat is the transfer of energy from a hotter body to a colder body. It is sometimes referred to as thermal energy. All chemical reactions involve a change in heat. There are three types of heat flow in substances: conduction, convection, and radiation. Conduction is the transfer of heat in solids. Convection is the transfer of heat in gases and liquids. Finally, radiation is the transfer of heat through space. Radiation is mainly responsible for the hotness we feel from the sun.

Measuring Heat

The most common way of measuring heat is with a calorimeter. The word calorimeter comes from the Latin word caloric, meaning heat. There are different types of calorimeters, and each type has a specific function and purpose. Reaction calorimeters are used to measure heat related to all chemical reactions. The bomb calorimeter, or constant-volume calorimeter, measures the heat of fuel combustion. Other types of calorimeters are the adiabatic calorimeter, constant pressure calorimeter, and Calvet-type calorimeter. In AP® Chemistry, heat is assigned a sign convention (positive or negative). The heat absorbed by the system will be positive (\text{heat} > 0), whereas heat released by the system will be negative (\text{heat} < 0). When heat is added to or removed from a substance, it will change its phase (latent heat) or increase its temperature (sensible heat).

Notation and Units

In AP® Chemistry calculations, heat is symbolized by Q. The \text{Joule (J)} is the SI unit for both heat and energy and is equal to \dfrac{1 \text{ kg} \cdot \text{m}^2}{s^2}.

The English unit for heat is a \text{British Thermal Unit (BTU)}. 1 \text{ BTU} is the energy needed to raise the temperature of 1 \text{ pound} of water by 1^\circ \text{F}. Another common unit of heat is a \text{calorie (cal)}, which is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 \text{ gram} of water by1^\circ \text{C}. \text{BTU} and \text{cal} are more commonly used in engineering applications than \text{J}. The conversion data below relates the three common units of heat.

1055 \text{ J} = 1 \text{ BTU}

4.186 \text{ J} = 1 \text{ cal}

1 \text{ BTU} = 252 \text{ cal}

In layman’s terms, heat is the ability to do work because it is a type of energy. On the other hand, temperature can be used to indicate the degree of heat in a substance. The table below shows other differences between temperature and heat.

Table 2. Temperature vs. Heat Summary

| Temperature | Heat | |

| Definition | Measure of the kinetic motion of substances | Energy transferred from a hotter to a colder body |

| Symbol in AP® Chemistry | T | Q |

| SI Unit | Kelvin (\text{K}) | Joule (\text{J}) |

| Other Units | Celsius (^\circ \text{C}) and Fahrenheit (^\circ \text{F}) | British Thermal Unit (\text{BTU}) and calorie (\text{cal}) |

| Particles | Indicates the speed of particles in a substance | Represents the total energy of all particles in a substance |

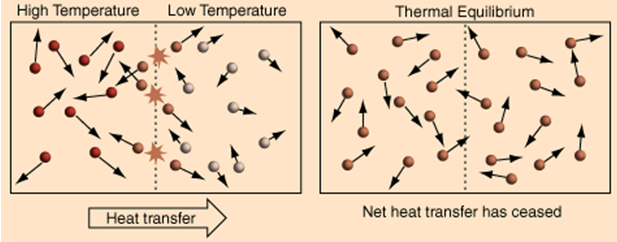

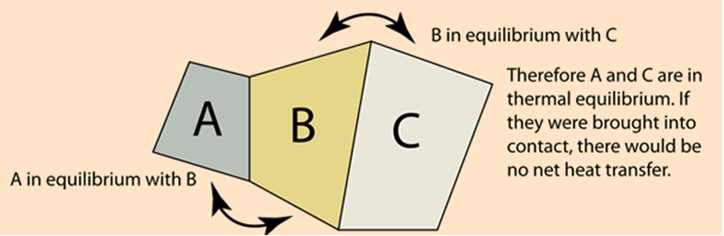

Now, I will discuss how heat and temperature are related to each other, through the laws of thermodynamics. The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics, also called the thermal equilibrium, connects temperature with heat flow. It states that if two systems are in thermal equilibrium with a third system, they are both in thermal equilibrium with one another. As illustrated below, we have Object A, which has a temperature of 89^\circ\text{C}; Object B, which has a temperature of 10^\circ\text{C}; and Object C, which has a temperature of 50^\circ\text{C}. If the three objects are in contact with one another, they will at some time reach thermal equilibrium.

Heat flows from the hotter body to the colder body. In this case, the thermal equilibrium temperature is 64^\circ\text{C}. This means that Objects B and C both will absorb heat, and Object A will release heat. After reaching the thermal equilibrium, heat transfer will stop. Therefore, Object A is in equilibrium with Object B, and Object B is in equilibrium with object C, and by the Zeroth Law, Object A is also in equilibrium with Object C.

Sensible heat is the heat added to a substance, resulting in an increase in temperature. Heat and temperature are related by the specific heat capacity, or the heat required by one unit mass to raise its temperature by one degree unit.

Q = mc_p (T_2-T_1)

…where Q = sensible heat, c_p = specific heat capacity, T_1 = initial temperature, and T_2 = final temperature.

Now that we have discussed the basic concepts on the differences of temperature and heat, we can now go through some practice problems in this AP® Chemistry review.

Calculations in AP® Chemistry

Sample Problem 1:

Convert the following temperature scale to the required scale.

a. 27^{\circ}\text{C} = ___ ^{\circ}\text{F}

{ T }_{ \left( { ^{\circ}\text{F} } \right) }=\dfrac { 9 }{ 5 } { T }_{ \left( ^{\circ}\text{C} \right) }+32

{ T }_{ \left( { ^{\circ}\text{F} } \right) }=\dfrac { 9 }{ 5 } { (27) }+32

{ T }_{ \left( { ^{\circ}\text{F} } \right) }=48.6+32

{ T }_{ \left( { ^{\circ}\text{F} } \right) }=80.6^{\circ}\text{F}

b. 398 \text{ K} = ___ ^{\circ}\text{C}

{ T }_{ \left( \text{K} \right) }=273+{ T }_{ \left( ^{\circ}\text{C} \right) }

398=273+{ T }_{ \left( ^{\circ}\text{C} \right) }

398-273={ T }_{ \left( ^{\circ}\text{C} \right) }

{ T }_{ \left( ^{\circ}\text{C} \right) }=125^{\circ}\text{C}

c. 324^{\circ}\text{F} = ___ ^{\circ}\text{C}

{ T }_{ \left( { ^{\circ}\text{C} } \right) }=\dfrac { 5 }{ 9 } \left( { T }_{ \left( ^{\circ}\text{F} \right) }-32 \right)

{ T }_{ \left( { ^{\circ}\text{C} } \right) }=\dfrac { 5 }{ 9 }(324-32)

{ T }_{ \left( { ^{\circ}\text{C} } \right) }=\dfrac { 5 }{ 9 }(292)

{ T }_{ \left( { ^{\circ}\text{C} } \right) }=162.22^{\circ}\text{C}

Sample Problem 2:

Suppose you need to raise the temperature of 52 \text{ g} of water from 34^\circ \text{C} to 59^\circ \text{C}. How much heat do you need to add? The specific heat capacity of water is 4.186 \text{ J} \cdot \text{g}^{-1} \cdot ^\circ \text{C}^{-1}.

Given data:

m = 52 \text{ g}

T_1 = 34^\circ \text{C}

T_2 =59^\circ \text{C}

c_p= 4.186\text{ J} \cdot \text{g}^{-1} \cdot ^\circ \text{C}^{-1}

Using the given formula:

Q = mc_p (T_2-T_1)

Q = (52 \text{ g}) (4.186\text{ J} \cdot \text{g}^{-1} \cdot ^\circ \text{C}^{-1}) (59^\circ \text{C} - 34^\circ \text{C})

Q = (52) (4.186) (25) \text{ J}

Q = 5{,}441.8 \text{ J}

Sample Problem 3:

Two metals are placed in a glass of water. Gold has a mass of 14 \text{ g} and an initial temperature of 50^\circ \text{C}. Aluminum has a mass of 30 \text{ g} and an initial temperature of 17^\circ \text{C}. The glass of water has a mass of 100 \text{ g} and a temperature of 40^\circ \text{C}. If the three substances were to reach thermal equilibrium, what is the final temperature of the system? The specific heats of gold, aluminum, and water are 0.129\text{ J} \cdot \text{g}^{-1} \cdot ^\circ \text{C}^{-1}, 0.90\text{ J} \cdot \text{g}^{-1} \cdot ^\circ \text{C}^{-1}, and 4.184\text{ J} \cdot \text{g}^{-1} \cdot ^\circ \text{C}^{-1}, respectively.

In thermal equilibrium, heat transfer is 0.

Q_{gold} + Q_{aluminium} + Q_{water} = 0

m_{gold}c_{p, gold}(T_2-T_{1, gold})+ m_{aluminium}c_{p,aluminium}(T_2-T_{1,aluminium}) + m_{water}c_{p,water}(T_2-T_{1,water})= 0

Substituting the given data:

(14\text{ g})(0.129\text{ J}\cdot\text{g}^{-1})(T_2 - 50^\circ\text{C})+(30 \text{ g}) (0.90\text{ J} \cdot\text{g}^{-1})(T_2 - 17^\circ \text{C})+(100 \text{ g})(4.184\text{ J}\cdot\text{g}^{-1})(T_2 - 40^\circ\text{C})=0

Performing the operation and simplifying:

1.806T_2 - 90.3 + 27T_2 - 459 + 418.4T_2 - 16736 = 0

1.806T_2+ 27T_2+ 418.4T_2= 90.3 + 459 + 16736

447.206T_2= 17285.3

T_2= 38.65^\circ \text{C}

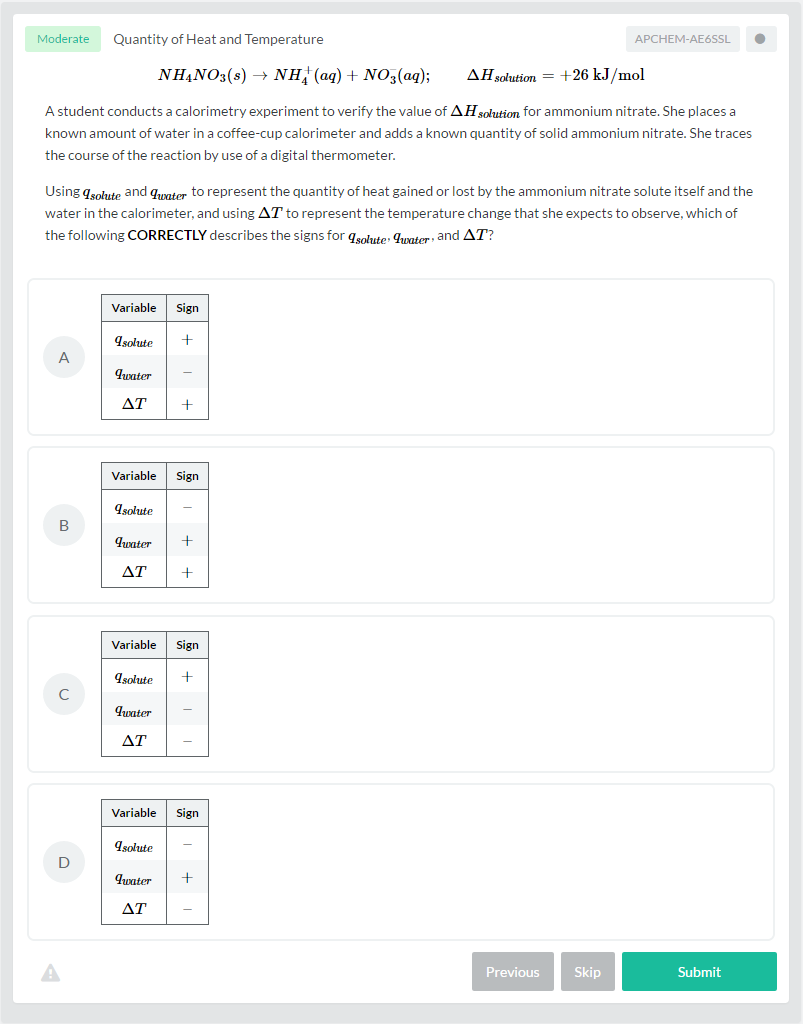

Let’s put everything into practice. Try this AP® Chemistry practice question:

Looking for more AP® Chemistry practice?

Check out our other articles on AP® Chemistry.

You can also find thousands of practice questions on Albert.io. Albert.io lets you customize your learning experience to target practice where you need the most help. We’ll give you challenging practice questions to help you achieve mastery of AP® Chemistry.

Start practicing here.

Are you a teacher or administrator interested in boosting AP® Chemistry student outcomes?

Learn more about our school licenses here.