The Advanced Placement (AP) English Language course aligns to an introductory college level rhetoric and writing curriculum. The AP® English Free Response Questions (FRQ’s) are aimed to evaluate students’ ability to develop evidence-based analytic and argumentative essays that go through several stages, which is especially true of the synthesis FRQ.

The synthesis FRQ gives students six sources with which to form and argue for a position on a topic the test provides. In order to score an 8 on the synthesis FRQ question, students need to write an essay that effectively argues a position, synthesizes at least 3 of the sources, uses appropriate and convincing evidence, and showcases a wide range of the elements of writing. Essays that score a 9 do all of that and demonstrate sophistication in their argument.

So how do you write an essay that does all of that in just 40 minutes? First, take a deep breath. And remember, you don’t have to do it on the fly. Prepare yourself. You are given a 15-minute planning period, so make sure that you use it to read the documents, label them, and ask yourself questions about them. Then, while writing the essay, interact with the sources. Don’t just regurgitate them. Use them to support your arguments and question them.

Use these strategies to calm down, be prepared, and write an essay that will earn you a 9 on the AP® English synthesis FRQ.

Read, Carefully, then Label Your Documents.

The AP® English test gives you fifteen minutes to read over the documents. Make sure that you use them! Read over the documents carefully, don’t skim them. Fully comprehend them, and try to understand their meaning. A deeper understanding of the documents will help you much more than a few extra minutes of writing time.

It can seem overwhelming to try and carefully read six sources in fifteen minutes. But the creators of the AP® English Language test don’t want to overwhelm you. Each source is roughly one page and one of the sources is visual–a graph, chart, or photograph. You have time to carefully read all of the documents that the AP® Language synthesis FRQ provides.

After you read each document, it’s a good idea to take a moment to label the documents. Think of the annotations as notes to a friend.

If you had to text your friend right before a test and tell them what this document was about, what would you say? Just write down one sentence or less that explains what the author said. It will help cement your understanding of the source and will help you keep track of all of them.

Here’s an example of a source from the 2014 AP® English synthesis FRQ.

As you are reading, circle and underline things that could be helpful to your later, like the words of the honor code in the first paragraph or the 157 students involved in the cheating scandal in the fourth.

But after you have finished reading, write a one-sentence summary near the top of the source. Think of this as your quick-label. For this source, a good example would be a sentence like: “Despite emphasis on not cheating, elite private school caught up in cheating scandal.” The label at the top will help you keep track of the documents. The labels within the documents will help you pull the best evidence to support your arguments. Reading the documents carefully helps you pull out the most important information.

Talk to Yourself. No, Really, it’s a Good Idea.

Before you start writing, craft a thesis. The thesis should be thoughtful and present an argument. One of the best ways to come up with a thesis for the synthesis FRQ, which asks students to formulate an argument, is to come up with several possible positions that you could take.

Then pick one. It can feel a little quick to be asked to form an opinion like that, and some students worry that the argument they come up with from this process won’t be good enough.

Don’t waffle on your opinion. The AP® FRQ is designed to evaluate how well students can synthesize documents and use them to support an argument. In other words, there is no right or wrong answer. As long as you can support your opinion with a well-crafted argument, it’s a good opinion. If you find yourself questioning it in the middle of your essay, just remind yourself to not worry about it.

Your thesis needs to be direct and specific. It shouldn’t give the reader any question as to what opinion you have decided to argue for. It should encompass your entire essay in just one sentence.

The 2014 AP® English synthesis FRQ asked students to synthesize information from six sources and “incorporate it into a coherent, well-developed argument for your own position on whether your school should establish, maintain, revise, or eliminate an honor code or honor system.” For this question:

Good thesis: My school should eliminate our current honor code because honor codes do not adequately prevent cheating and are often used in place of teaching students the ethical reasons for not cheating, as shown by recent scandals both in and out of school.

This thesis breaks down a chronological argument whose evidence can be drawn from the documents. Just reading the thesis tells you that this student’s essay will a) prove that honor codes do not prevent cheating, b) discuss the idea that honor codes promote repeat-after-me ethics over actual understanding and c) draw on examples of cheating in school and out of school (which will be drawn from the documents).

Bad thesis: My school should maintain their current honor code because I don’t cheat, but it should revise it for all the other students who do.

This is not a good thesis because it is not at all clear whether the student is going to argue that their school should maintain their honor code or revise their honor code. The student is waffling on their opinion and the reader will definitely have some questions. The thesis is not specific or direct.

Take your well-crafted thesis and try pretending, briefly, that you sent your thesis to the author of the sources. What would they say? Would they agree or disagree? What parts of their own sources would they bring up? Use that imaginary conversation to help write your outline.

Talking to yourself like this may feel odd, but in the context of writing an essay, it is the best way to organize your thoughts. It will help you to come up with several ideas, pick an opinion, craft a good thesis, and sketch out a good outline.

Resist the Urge to Summarize the Sources.

It is so tempting to summarize the sources, especially when you are in the middle of your synthesis essay and worried you are running out of time. Resist that temptation.

It is important to use the sources in front of your to inform your FRQ response. But the graders of the AP® English test do not want you to simply summarize the sources. They’ve read them.

Try to take a deep breath and instead go for short quotations and paraphrasing. Go back to your notes and read what you underlined to see if it is helpful for quick quotations.

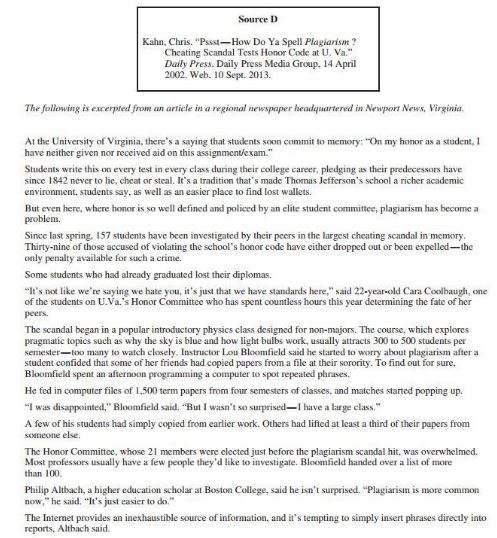

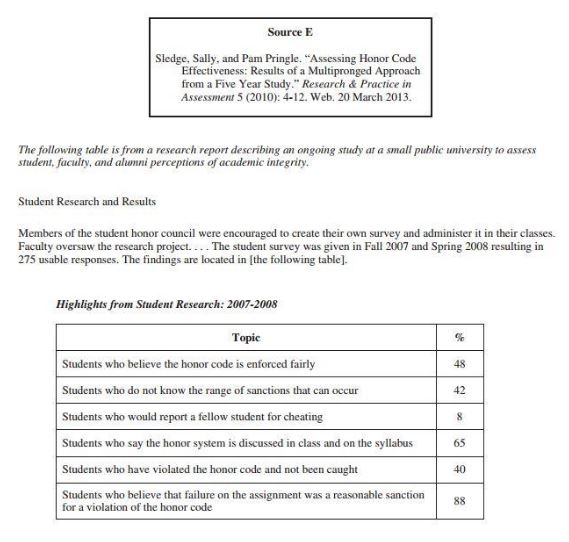

Look at another source from the 2014 AP® English synthesis FRQ:

If a student wanted to use this source as support for eliminating honor codes on the basis that they do not work, here is an example of summarizing the source and analyzing the analysis for support.

Summary: Honor codes do not work because only 48% of survey respondents at a small public university believed the honor code was enforced fairly. Only 42% knew the range of sanctions that can occur and just 8% would report a fellow student for cheating. 65% of students say the honor system is discussed in class and on the syllabus and 40% of students have violated the honor code and not been caught. Clearly, honor codes do not work.

Instead of adding to the information from the source, the student just rewrote the information from the source. The student does not include information that the reader cannot get from reading the document.

Analysis: Honor codes are ineffective at preventing cheating. Often, the perception of the honor code varies from the intention of the honor code. It is written to sound as if it will be strictly enforced, but students do not perceive it to be. For example, when students from a small, public university were surveyed, 40% of them admitted to having violated the honor code and gotten away with it, and only 8% of them would report another student for having violated it. While the wording of the honor code was not provided, and so it is unclear how harsh the punishments it promises are, clearly students do not take it seriously. There’s a disconnect between intent and execution, where the school says the honor code is important, but student think it is enforced unfairly, often because they have violated it themselves or they know someone who has.

This paragraph uses the source to support a point. The student is trying to convey that the school appears to take honor codes seriously, but students do not perceive that they do so. The student does not summarize the entire source, but instead pulls two statistics from it and use them to support their argument.

Remember, even if you are running out of time, that quality is always better than quantity on the AP® Language FRQ responses. Take the time to really support your arguments with good quotations instead of stuffing up the rest of your space with summary.

Question the Sources.

Don’t just accept the sources at face value. Pretend that, instead of encountering the sources on the AP® English exam you found them on the Internet. Would you buy them? Why or why not?

The AP® synthesis FRQ graders will appreciate that same type of thinking. Each source comes with a description, at the top, with the name, origin, and author of the source. Use that information to question the sources. Be cynical about the sources and be critical of the information they provide you, if it is appropriate.

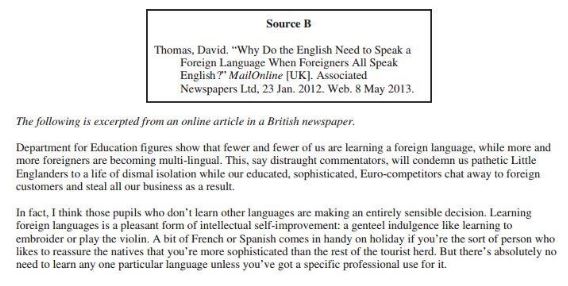

Take this excerpt from Source B of the 2016 AP® English synthesis FRQ.

The 2016 question had to do with the educational benefits of learning a foreign language. This David Thomas piece is one of the sources. Here’s a good way to question that source:

Look at the top–the little box at the top of the source contains a treasure trove of information. It says who wrote the article, when they wrote it, and who published the article.

In the case of this source, it was published by Mail Online, an online magazine. As students know, online magazines compete for page views and are interested in selling ads. Rehashing the same ideas does not attract viewers in the same way that being a little controversial does. So, in the case of David Thomas, this piece was written partially to say something different than the rest of the UK and to attract attention to an online magazine.

Questioning the sources does not mean dismissing them. The above analysis isn’t to suggest that David Thomas does not believe what he has written, or that he was simply trying to be contrarian; only that the purpose of an article written for an online opinion column is fundamentally different than an article written in an academic journal, for example. That purpose is reflected in the language and subject matter of the piece.

Treat the sources on the AP® English test the way you would treat sources in the real world. If you wouldn’t believe it if someone shared it as a Facebook status, bringing that disbelief into your essay demonstrates your critical thinking abilities. Just make sure you can back it up and give good reasons for questioning your sources.

Plan to Address the Opposition.

Remember when you came up with several possible responses you could have made to the prompt? Addressing some of them increases the sophistication of your argument astronomically.

The AP® English synthesis FRQ is largely about how well you can handle making an argument. A huge part of good argument involves thinking about the opposition. Take time to engage with the opposite opinion to the one you put forward.

To Sum up!

Following these five strategies will ensure a 9 on the AP® English synthesis FRQ and, hopefully, a 5 on the AP® English test. Prepare yourself by reading carefully and labeling the documents. Interact with the documents by explaining them to yourself, using them for support, and questioning them when necessary.

Let’s put everything into practice. Try this AP® English Language practice question:

Looking for more AP® English Language practice?

Check out our other articles on AP® English Language.

You can also find thousands of practice questions on Albert.io. Albert.io lets you customize your learning experience to target practice where you need the most help. We’ll give you challenging practice questions to help you achieve mastery of AP® English Language.

Start practicing here.

Are you a teacher or administrator interested in boosting AP® English Language student outcomes?

Learn more about our school licenses here.