What We Review

Introduction

Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium is a cornerstone concept in population genetics. It provides a theoretical framework for predicting allele frequencies in a hypothetical, non-evolving population. Although real populations rarely meet all the conditions for perfect equilibrium, understanding this model helps clarify how evolutionary processes—such as mutation, selection, and migration—act on gene pools. In this post, we’ll explore what Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium is, examine its requirements, learn how to use its equation, and see why it’s so important for AP® Biology and beyond.

What is Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium?

Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium describes a theoretical situation in which allele frequencies remain constant over time, meaning no evolution occurs. It’s an idealized model based on five key assumptions (or conditions) that prevent changes in a population’s genetic structure. By comparing real-world data to this model, biologists can determine whether a population is evolving and identify factors driving genetic change.

The Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium Equation

At the heart of this concept is the Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium equation:

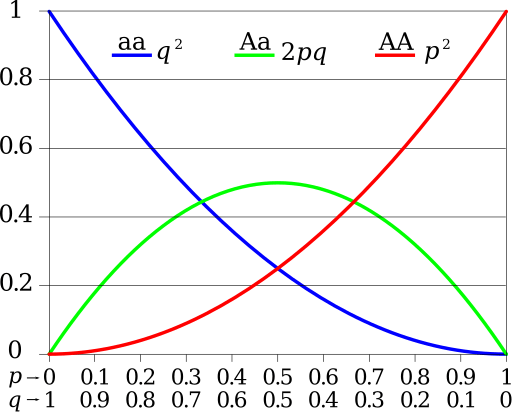

p² + 2pq + q² = 1Here:

- p = frequency of the dominant allele (A)

- q = frequency of the recessive allele (a)

- p + q = 1

In a population that meets the Hardy Weinberg conditions, genotype frequencies are given by p² \text{ }(AA), 2pq\text{ }(Aa), and q²\text{ }(aa).

Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium Requirements

For a population to remain in Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium, five conditions must all be met:

- Large Population Size

- When a population is very large, random fluctuations in allele frequencies (genetic drift) are minimized. Small populations are more susceptible to sampling errors that can shift allele frequencies dramatically from one generation to the next.

- Absence of Migration

- No individuals can enter or leave the population. In real populations, migration can bring in new alleles or remove existing ones, altering the gene pool.

- No Net Mutations

- Mutations introduce new alleles or change existing ones. While some level of mutation is natural, the Hardy Weinberg model assumes no net effect of mutation on allele frequencies.

- Random Mating

- Every individual must have an equal chance of mating with any other. Nonrandom mating—such as sexual selection or inbreeding—can change genotype frequencies.

- Absence of Selection

- Natural selection, artificial selection, or any other form of selection must not favor any specific allele. When certain traits confer a survival or reproductive advantage, allele frequencies change over time.

Implications of Not Meeting Hardy Weinberg Conditions

In reality, most populations do not meet all these conditions. When any one requirement is not satisfied, allele frequencies shift, and evolution can occur. For instance:

- In small populations, genetic drift can rapidly fix or eliminate alleles.

- Migration introduces new alleles or removes them, potentially altering local adaptations.

- Mutations can create genetic novelty.

- In nonrandom mating, certain genotypes might be more frequent than predicted.

- Selection pressures systematically increase or decrease specific allele frequencies.

These shifts highlight the dynamic nature of evolution and help us understand why real populations rarely remain in perfect equilibrium.

Calculating Allele Frequencies from Genotype Frequencies

Hardy Weinberg calculations often start with observed genotype frequencies and work backward to find p and q. For example:

- Suppose you have a population in which 36% of individuals exhibit the recessive phenotype (aa).

- Then q² = 0.36 → q = 0.6.

- Because p + q = 1, p = 0.4.

From there, you can calculate the expected genotype frequencies:

- AA: p² = (0.4)² = 0.16 (16\%)

- Aa: 2pq = 2 × 0.4 × 0.6 = 0.48 (48\%)

- aa: q² = (0.6)² = 0.36 (36%)

This process allows a comparison between observed genotype frequencies and those predicted by the model. Significant deviations can suggest that one or more of the Hardy Weinberg requirements is not being met.

Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium Examples

- Hypothetical Stable Population: Imagine an extremely large population of bacteria where mutation is negligible and migration is restricted by physical barriers. If mating (gene exchange) is random and selection pressures are minimal, the population might display genotype frequencies that are very close to Hardy Weinberg predictions.

- Human Blood Groups: In some large human populations, certain blood group alleles can approximate Hardy Weinberg proportions because selection for these alleles is often not strong enough to shift the frequencies drastically, and mating for blood type is largely random.

When real populations deviate from these scenarios, the differences often illustrate evolutionary mechanisms at work—through selection, migration, or genetic drift.

Conclusion

Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium is crucial for understanding the baseline against which we measure evolutionary change. By learning its assumptions, mastering the equation, and practicing calculations, you gain a powerful tool to evaluate how and why allele frequencies shift in real populations. As you prepare for the AP® Biology exam, be sure to connect these concepts to broader topics in evolution, genetics, and population biology. Knowing not just the equation but also the real-world implications of failing each requirement will help you excel in your studies and deepen your appreciation of population genetics.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Biology

Are you preparing for the AP® Biology test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world math problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

Need help preparing for your AP® Biology exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Biology practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.