Antibiotics have been a cornerstone of modern medicine for decades. They serve as powerful tools to combat bacterial infections, from mild ear infections to life-threatening conditions such as pneumonia. However, increasing evidence shows that many bacteria are becoming more dangerous due to antibiotic resistance. Understanding how does antibiotic resistance occur provides critical insights for preventing the spread of difficult-to-treat infections.

Below is a comprehensive look at antibiotic resistance, including how it develops, what contributes to its spread, and strategies to limit its impact. The explanations here aim to be clear and concise, helping learners grasp the essentials of this important topic.

What We Review

Introduction

Antibiotics help treat illnesses by targeting harmful bacteria inside the body. Their discovery revolutionized healthcare and saved countless lives worldwide. Unfortunately, over time, more bacteria have gained the ability to withstand antibiotic treatment.

Therefore, it is valuable to explore the concept of antibiotic resistance and recognize how it emerges. This knowledge allows for better decision-making about when and how to use antibiotics. Moreover, it highlights why it is crucial to continue researching new medications and methods to combat these evolving pathogens.

What Is Antibiotic Resistance?

Antibiotic resistance refers to a bacterium’s ability to survive and multiply even after exposure to an antibiotic. This means that the drug loses its capacity to eliminate or control the infection effectively.

Often, people assume that if a medication worked once, it will work again. However, bacteria can change genetically to defend themselves against repeated treatments. Over time, repeated use of the same medicines can encourage the growth of these tougher bacteria.

Misconceptions also arise when individuals believe antibiotics can cure viral infections. Antibiotics only target bacteria. They do not affect viruses, which is why a cold or flu (both caused by viruses) will not respond to antibiotic treatment.

How Do Antibiotics Work?

Antibiotics can target bacteria in different ways:

- Targeting Bacterial Cell Walls: Some antibiotics, such as penicillin, disrupt cell wall production. Without a strong cell wall, bacteria can burst and die.

- Inhibiting Protein Synthesis: Certain antibiotics interfere with bacterial ribosomes, stopping them from making essential proteins.

- Affecting Nucleic Acid Synthesis: Other antibiotics prevent bacteria from copying their DNA or RNA. When this occurs, the bacteria can no longer reproduce properly.

Since bacteria are single-celled organisms with unique structures, these methods are highly effective. Meanwhile, viruses use host cells for replication and typically lack such structures. Therefore, antibiotics do not work on viruses, which is a crucial difference to keep in mind when considering virus evolution versus bacterial evolution.

How Do Bacteria Become Resistant to Antibiotics?

Bacteria become resistant through genetic changes. These changes occur by:

- Genetic Mutations: A random error in the bacterium’s DNA might give it a survival advantage. If the bacterium encounters an antibiotic, that random mutation might help it resist destruction.

- Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT): Bacteria can exchange genetic material directly with one another. When one strain carries a resistance gene, it can pass it to another bacterium through processes like conjugation (via direct contact), transformation (taking up DNA from the environment), or transduction (using viruses called bacteriophages to transfer DNA).

Over time, bacteria with these beneficial genes outcompete more vulnerable bacteria. This process is a classic example of evolution by natural selection.

Example: Step-by-Step Analysis of Antibiotic Resistance Development

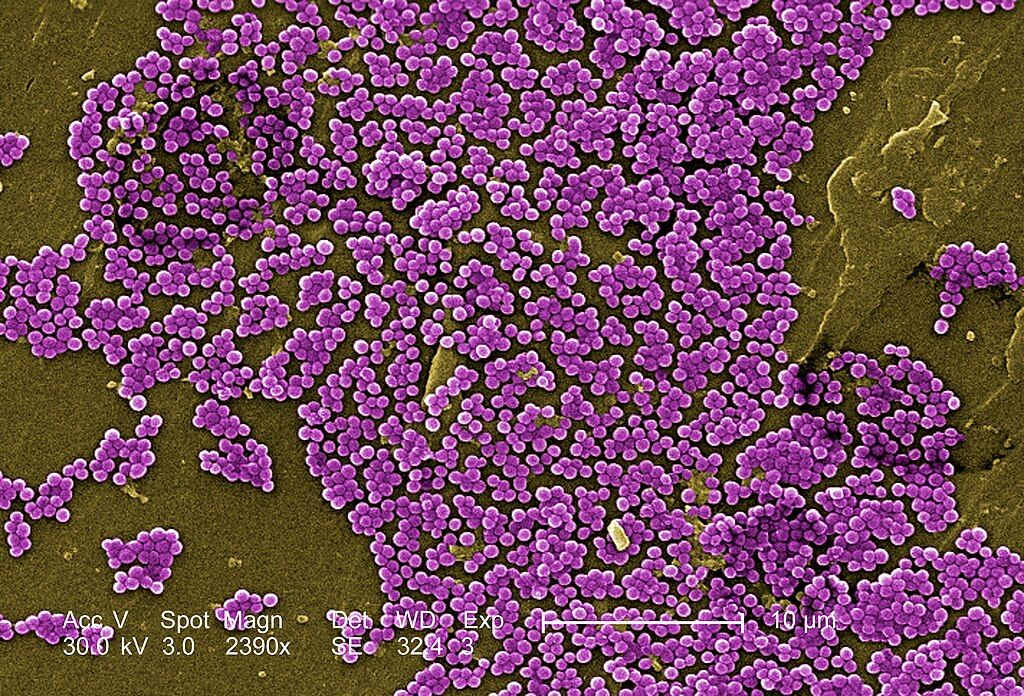

Consider the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, which commonly lives on the skin or in the nose:

- Original Susceptibility: Initially, the entire population of S. aureus is sensitive to a specific antibiotic.

- Mutation Occurs: Randomly, a single cell undergoes a genetic mutation that allows it to survive exposure to the antibiotic.

- Selective Survival: When the antibiotic is used, all non-resistant bacteria die. However, the mutant cell with the resistance gene survives.

- Reproduction of Resistant Bacteria: The surviving mutant bacterium reproduces, creating more cells that share the resistance trait.

- Population Shift: Over time, most cells in the population are resistant, making the antibiotic less effective.

Hence, continuous or improper use of the same medication can quickly increase the frequency of these resistant bacteria.

Factors Contributing to Antibiotic Resistance

Numerous factors increase the risk of antibiotic resistance worldwide:

- Overuse and Misuse: In healthcare, antibiotics are sometimes prescribed to treat viral infections or mild conditions. This unnecessary use can speed up resistance.

- Use in Agriculture: Antibiotics are often given to livestock to promote growth and prevent infections. Consequently, resistant bacteria can spread to humans through the food chain and the environment.

- Patient Misunderstanding: When patients stop taking prescribed antibiotics too soon, some bacteria survive and become more resistant. Meanwhile, taking leftover antibiotics without consulting a healthcare provider can also worsen the problem.

- Environmental Impact: Resistant genes can move through water, soil, and industrial waste, further dispersing across communities.

The Evolution of Pathogenic Variants

Bacteria evolve rapidly, producing what scientists call “pathogenic variants.” A pathogenic variant is a strain that has acquired harmful traits, such as high resistance. These new forms pose risks because treatments become limited.

In contrast, viruses can also mutate, leading to virus evolution. However, antibiotic resistance specifically involves bacteria. When both bacteria and viruses evolve, they can pose challenges to public health but in different ways. Therefore, it is vital to address each threat with targeted strategies.

Example: Pathogen Evolution Case Study

One prominent example is Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA):

- Initial Use of Methicillin: Physicians started using methicillin to treat S. aureus infections that no longer responded to penicillin.

- Mutation and Survival: A subset of S. aureus had a gene that produced an altered penicillin-binding protein, preventing methicillin from disabling it.

- Emergence and Spread: Once methicillin entered widespread use, the resistant cells gained a significant advantage and spread swiftly among patients in hospitals.

- Impact on Healthcare: MRSA infections became more common, increasing hospital stays, costs, and risks of complications.

- Ongoing Management: New antibiotics and strict infection control measures were introduced to limit MRSA outbreaks, demonstrating the continuous need for innovation.

Strategies to Combat Antibiotic Resistance

Addressing antibiotic resistance effectively requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Antibiotic Stewardship: Healthcare professionals should prescribe antibiotics only when necessary and ensure the right drug is chosen at the correct dose.

- Public Health Initiatives: Programs that track resistant infections help identify trends and guide interventions. Education campaigns encourage people to follow prescription instructions.

- Research and Development: Scientists actively seek new antibiotics, vaccines, and alternative methods, such as phage therapy, to overcome resistance.

- Responsible Agriculture: Reducing the subtherapeutic use of antibiotics in farm animals lowers the risk of resistant strains reaching the human population.

- Patient Awareness: Ensuring that patients complete their antibiotic courses prevents surviving bacteria from regaining strength. Minimizing the misuse of leftover antibiotics is also key.

Summary

Antibiotic resistance arises when bacteria adapt to survive treatments intended to eliminate them. Through genetic mutations or horizontal gene transfer, they can quickly develop mechanisms that render antibiotics ineffective. Furthermore, the overuse and misuse of antibiotics in humans, animals, and agriculture contribute to the rapid growth of resistant strains.

Understanding how bacteria evolve and become these pathogenic variants is crucial. By examining specific cases like MRSA, one can see how improper antibiotic usage can drive the evolution of hard-to-treat infections. Therefore, continual research, responsible prescribing, and public health measures are essential for slowing resistance.

Quick Reference Chart

| Term | Definition or Key Feature |

| Antibiotic | A substance that kills or inhibits the growth of bacteria. |

| Antibiotic Resistance | The ability of bacteria to survive and multiply despite antibiotic treatment. |

| Mutation | A change in the DNA sequence that may lead to new traits. |

| Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) | Transfer of genes between bacteria through conjugation, transformation, or transduction. |

| Pathogenic Variant | A bacterial strain that has acquired harmful traits, such as antibiotic resistance. |

| Virus Evolution | The process by which viruses change over time, often involving mutations in their genetic material. |

| MRSA | Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a strain resistant to many beta-lactam antibiotics. |

| Antibiotic Stewardship | The responsible use of antibiotics to minimize resistance and preserve effectiveness. |

Practice: Bacterial Growth Equation

Bacteria often reproduce by binary fission, leading to exponential growth under favorable conditions. The growth can be modeled by the equation:

N(t) = N_0 \cdot e^{kt}where:

- N_0 is the initial number of bacterial cells,

- N(t) is the number of cells after time t,

- k is the growth rate constant,

- t is time.

Practice Problem and Step-by-Step Solution

A bacterial culture starts with N_0 = 1000 cells and doubles every hour. After 5 hours, estimate the number of cells.

- Identify the growth rate: Doubling every hour means the population multiplies by 2 in 1 hour. Therefore, e^{k \cdot 1} = 2.

- Solve for k:k = \ln(2).

- Substitute into the growth formula for t = 5 hours:N(5) = 1000 \cdot e^{(\ln(2) \cdot 5)}.

- Simplify:N(5) = 1000 \cdot (e^{\ln(2)})^5 = 1000 \cdot 2^5 = 1000 \cdot 32 = 32000.

Hence, there would be approximately 32,000 bacterial cells after 5 hours.

Conclusion

Without proper measures, antibiotic resistance can undermine the great progress achieved in treating bacterial infections. Although bacteria evolve rapidly, it is possible to stay ahead by using antibiotics judiciously, promoting research into new treatments, and improving public awareness. Each step—whether it involves completing a prescription or encouraging responsible use in agriculture—helps slow the rise of resistant bacteria and preserve these life-saving drugs for future generations.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Biology

Are you preparing for the AP® Biology test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world math problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

Need help preparing for your AP® Biology exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Biology practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.