As you probably know by now, taking AP® classes and exams is a huge undertaking. Not only is the information that you need to learn complex, but there’s also ton of it to keep track of. This is especially true for AP® Biology, which places two semester’s worth of college-level biology into one exam. And even with recent adjustments to the test, AP® Biology still has one of the greatest volumes of content that you will find in any AP® exam. It takes some skill and know-how to study for AP® Biology exam, and this article is going to give you the tools you need to meet this challenge head on.

What We Review

How to Study for AP® Biology: What’s on the AP® Biology Exam

AP® Biology Exam Format

The first step in figuring out how to study for AP® Biology is knowing what will be on the test and how it will be presented. Luckily, the structure of the exam itself is not particularly complex. The entire exam is 3 hours and is composed of two sections. The first section (90 minutes) focuses on discrete answers to questions in the form of 63 multiple choice question and 6 grid-in questions. The second section (also 90 minutes) requires writing out answers in the form of 2 long and 6 short response questions.

Learning Objectives in AP® Biology

Knowing the test structure will keep you from getting shocked and panicked at the first sight of it, but most of your focus should be on the actual biological content of the exam. AP® Biology has a reputation for having a lot to memorize, but it actually isn’t that helpful to just know a ton of facts. You need to know when a given piece of information is relevant and how it can be used to evaluate claims, make predictions, and accomplish goals. Knowledge without context is no more than trivia, and the College Board is not interested in trivia.

What the College Board is interested in are the learning objectives of AP® Biology. These objective are listed in the AP® Biology Course and Exam Description and briefly summarize everything there is to know for the AP® Bio exam. For example, learning objective 2.29 states: “The student can create representations and models to describe immune responses.” This means that you should be able to create and analyze sketches that correctly describe immune responses. Let’s look at a question recommended by the College Board.

A pathogen bacterium has been engulfed by a phagocytic cell as part of the nonspecific (innate) immune response. Which of the following illustrations best represents the response?

To answer this question, you must know the key features of this process, how they are arranged spatially, and how that arrangement changes over time as denoted by the arrows. In this case, C does the best job depicting this process.

Using the learning objectives as a checklist while you study will make it harder to forget an important topic. You should not attempt to memorize the learning objectives in any way, but have the list in your digital or paper notes as a reference. If you’re reading over a learning objective and you don’t believe you have met that objective, it is an area you should definitely study.

Essential Knowledge Statements

In addition to making a handy checklist, the learning objectives are also the best entry point for more detailed information about the AP® Biology curriculum. Each learning objective is composed of exactly one essential knowledge statement and one or more science practices. We’ll discuss the science practices a bit later, but for now, let’s focus on the types of information that essential knowledge statements have to offer.

For example, learning objective 2.29 also tells us to reference essential knowledge 2.D.4 (as well as Science Practice 1.1 and 1.2) which states: “Plants and animals have a variety of chemical defenses against infections that affect dynamic homeostasis.” This general statement is then broken down into sub-points. You probably don’t need to read the whole statement right now, but there are some special notes included with the essential knowledge that are definitely worth a look.

Illustrative Examples

The first sub-point includes the comment “Students should be able to demonstrate understanding of the above concept by using an illustrative example such as:” and goes on to list examples. This statement signifies that while the exam will not test you directly on knowing specific examples of the essential knowledge statement, being able to provide such an example is evidence that you are grasping the material. Do your best to learn such examples (they actually do make the concepts much clearer), but if you are pressed for time, these are probably the safest things to deemphasize when studying.

Underlying Content

The second sub-point states “Evidence of student learning is a demonstrated understanding of each of the following:” and then enumerates the underlying content that you should know for the exam. You and your teacher may find additional examples to be helpful, but make sure you know the ones listed here. The College Board expects you to know this information, so prepare to see these examples in any part of the exam.

Exclusion Statements

The last content note to watch out for are exclusion statements, which tell you what won’t be on the exam. When studying cell division for example, “Memorization of the names of the phases of mitosis is beyond the scope of the course and the AP® Exam.” You do need to know the order of steps in mitosis, but you don’t need to spend time learning the names of each step for the AP® exam. There’s no way to learn everything about biology in one class (or one lifetime!) so use the essential knowledge statements and their content notes to plan how you study for AP® Biology and spend your time wisely.

AP® Biology Labs

Experimentation and lab work is a big part of science. In AP® Biology these skills are developed through laboratory experiments and related assignments. For each of the Big Ideas of AP® Biology, the College Board recommends a few labs. There isn’t a lab portion of the exam, but some aspects of experimental designs can show up in any section. Take this question from a College Board practice AP® Biology exam:

During aerobic cellular respiration, oxygen gas is consumed at the same rate as carbon dioxide gas is produced. In order to provide accurate volumetric measurements of oxygen gas consumption, the experimental setup should include which of the following?

(A) A substance that removes carbon dioxide gas

(B) A plant to produce oxygen

(C) A glucose reserve

(D) A valve to release excess water

Source: AP® Biology Course and Exam Description

You could certainly answer this question by remembering the properties of gasses, but this concept is not covered in the learning objectives. The question is actually a direct reference to the Cellular Respiration lab recommended by the College Board, which uses potassium hydroxide to remove carbon dioxide from a respirometer. In addition to helping with direct questions like this, studying labs also act as a great examples of learning objectives in practice. Your class may not perform all of the recommended labs, but you can find the experimental procedures from the College Board.

Return to the Table of Contents

Gathering Your Resources for the AP® Biology Exam

The next step in studying for the AP® Biology exam is gathering the resources you need to be successful. Textbooks can be great to reference, but there are also many web articles, tutorial videos, and practice questions available online. You have to be a bit selective with what information you trust, but if you are willing to look, there’s a great chance of finding resources that fit your learning style. Here’s a starter list for resources.

College Board Materials for AP® Biology

AP® Biology Course and Exam Description – Complete curriculum guide with sample problems

AP® Biology Investigative Labs: An Inquiry-Based Approach – Recommended AP® Biology labs with procedures, explanations, and related learning objectives

AP® Biology Practice Exam and Notes – Official, full-length practice exam. It includes answers and curriculum breakdowns for each question

AP® Biology Equation and Formulas – This list will be provided for you with your exam. Don’t assume that being given equations means they don’t need to be studied. Make sure that you know what all the variables mean and what situations require these equations.

Past Free Response Question– These are probably your best resource for becoming familiar with the written section of the exam. Many of these are from older forms of the exam, so check the current curriculum to see what information is still tested.

Videos for AP® Biology Content

Bozeman Science – These videos cover major topics in each of the Big Ideas and even includes discussions of each science practice in AP® Biology.

Khan Academy – These videos are not directly tied to the AP® Biology curriculum, but still cover many of the same topics.

Albert.io AP® Biology Posts

We also have a large catalogue of AP® Biology posts that cover core topics, study guides, product reviews, and more. You can browse all of the posts here, but here are a couple to start with:

AP® Biology Review Guide – This free guide is a great for students needing direction on getting started in their exam prep.

How to Write Effective AP® Biology FRQs – This guide provides the written-version of the videos embedded above.

Return to the Table of Contents

How to Study for AP® Biology: Testing Yourself Before the AP® Biology Exam

Reading textbooks and notes or watching videos is a fantastic way to build your knowledge, but knowledge by itself does not translate directly to better exam scores. Demonstrating and communicating your knowledge is a skill, and like any skill, you must practice to master it. Old free response questions can be found on the College Board’s website, multiple choice questions can be found in sources such as review books and Albert.io’s AP® Biology section. The exam has changed over the years, so try to find recent examples if possible. Older exams are still useful, but consult current AP® Biology curriculum to avoid spending too much time on topics that are no longer tested.

Conditions

At some point you will want to try an exam under conditions as similar as possible to the real exam, but this may not be the most effective way to begin your studies. Specifically, if you have access to more than one practice exam, don’t stress about time during your first practice. You should absolutely measure how long it takes you finish a given number of questions, but it’s probably not helpful to give yourself a time limit. Work through the problems at a comfortable pace and see how long it takes you. The current exam gives you 90 minutes to answer 63 multiple choice questions and 6 grid in questions, so you will eventually want to be able to answer multiple choice questions in a minute or less (on average) and split the remaining 27 minutes among the grid-in questions, which are often more time consuming.

Once you have finished your practice exam problems, the next step is to grade and analyze your results. Grading is often straightforward, but there are a couple things to keep in mind for later analysis: Accuracy and Timing

Accuracy

The most obvious and objective way to assess your understanding is noting which questions you answered right and which you answered incorrectly. In addition to this, try to remember how difficult the question felt. A question that was difficult to answer but was ultimately correct may still be worth further study. If you got the answer right by guessing (which you should always do when you do not know the answer; the AP® Biology exam does not penalize incorrect answers.) you should consider the question incorrect for the purpose of studying. If you felt a question was easy but you got it incorrect, you definitely need to figure out why. If it is not related to actual biology (content or science practices) there was likely a “trick” that you need to note (discussed below). If it was biology related, there is probably a fundamental misconception that needs to be addressed.

Timing

In addition to right or wrong, note how long it took to answer questions. You don’t need exact times; a general sense of fast, normal, and slow is sufficient. Try to gauge if the question took a long time because they were more involved (more reading, calculations, diagrams were necessary) or if they took more time because you did not have a strong grasp on the material. If you found yourself rereading the question 3 or more times, you made 3 or more failing strategies, or you sat staring at the problem without working for a long time, these are signs that you were not familiar enough with the content presented and need to study more.

Some questions just take more time, and extra studying won’t change that. Make note of these questions and try to recognize by sight which questions take more time. Each multiple choice question is worth the same, so if you feel pressed for time during an exam, you can skip longer questions during your first pass through, and come back to them with your remaining time. Just be sure to record your answers carefully if you are skipping questions.

Return to the Table of Contents

Analyzing Your Results

It’s not enough to just know which individual questions you got correct or incorrect during a practice exam. You aren’t likely to see exactly the same questions on your actual exam, so it is more important to identify trends that will show you how to study for AP® Biology more effectively. We recommend categorizing your questions using (at least) the following methods:

1) State why you answered specific questions incorrectly.

This is not meant to assign blame or make excuses, but to give you a general idea of how to improve. Try summarizing the main issue in one phrase or sentence. For example, “I forgot the steps in respiration,” “I had a hard time reading the graph,” and “I confused phenotype with genotype” are all simple descriptions of what went wrong with a question. If you find yourself repeating the same words, that will identify an area to revisit.

For example, if you have “forgotten” multiple things, you will need to invest in memorization strategies to keep track of the large volume of information in AP® Biology. If you “confused” or “mixed-up” multiple pairs of terms, make it a habit compare and contrast similar terms with lists or Venn diagrams. If you “typed the wrong thing in your calculator” or “made silly math errors” focus your studies on calculations and give math problems more attention during the exam. The statements generated by this method can sometimes be too specific and variable to find large patterns, but it’s guaranteed to give you at least a few useful shortcomings to reflect upon.

2) Categorize strengths and weaknesses by content areas.

As mentioned above, the learning objectives are specific pieces of biology curriculum which can be categorized as part of particular essential knowledge. These essential knowledge statements are grouped by “Enduring Understanding” statements, which in turn are grouped into the four “Big Ideas” of AP® Biology. For example, if you were studying how organisms obtain free energy from glucose, that topic falls under Essential Knowledge 2.A.2 “Organisms capture and store free energy for use in biological processes.” More broadly, this fits into Enduring understanding 2.A which focus on how organisms acquire and store free energy. Finally, the College Board categorizes all of this as part of Big Idea #2 which covers how organisms use free energy and various molecules to employ their life processes.

As a student, you should not make any attempt to memorize these classifications (you have enough to study), but this organization will make it easier to keep track of all of the topics that you need to study, and it will give you some ideas as to the types of connections the College Board wants you to make. Take note of which sections are giving you trouble and which ones you understand well.

3) Categorize strengths and weaknesses by science practices.

One thing to keep in mind as you study, is that the AP® exam does not just focus on accumulated knowledge but also what you can do with this knowledge. These skills are summarized by the College Board as science practices, and can be found in the AP® Biology Course and Exam Description. There are seven science practices outlined by the College Board, and you want to be able to apply these practices within each domain (topic) in AP® Biology. Try to identify both the topics and the science practices in the questions you try, and keep track of strengths and weaknesses in science practices. As you study through topics, apply as many of the science practices to the topic at hand as possible, and pay special attention to your weakest one or two science practices.

4) Note how often you fell for “tricks” or other non-biology related mistakes.

For certain questions that you get wrong, you will feel that you understand the content area and are comfortable with the science practices that are being tested, but something about the structure of the question or answer choices was confusing. These are important to note as well, and can even help you on exams outside of AP® Biology. The most common tricks, such as having to find the answer that does NOT match a description, catch people who are not reading carefully. The fact that the exam is timed tempts every student to skim through questions and answers to save time. Noting every time that you miss a question because you weren’t reading carefully will definitely curb this temptation.

Return to the Table of Contents

How to Study for AP® Biology: Adjusting Your Strategies for the AP® Biology Exam

Once you have identified your stronger and weaker areas, you can use these to refine your study habits. Many students only focus on the weak areas that have been identified, but understanding both strengths and weaknesses will greatly enhance your studying. Here are a few tips for using your strengths and weaknesses to your advantage.

1) Don’t neglect improving stronger areas.

While there is a lot of merit in focusing on weaker areas, keep in mind that questions in your strongest topic are worth as much as questions in your weakest topic. While it is true that your weaker areas have more room for growth, it is also possible that you can improve your strong categories faster because you already have a better grasp on that material. Don’t spend all or even most of your time on your best topics, but also don’t assume that they don’t need to be studied. After focusing on two or three weaker sections, review one of your better topics and try to perfect your understanding. This will also ensure that you don’t forget the easy stuff and lose valuable points on your exam.

2) Relate strong content areas to weak ones.

There’s probably some element or structure about certain subjects that makes them easier for you to understand. It would be great if you could isolate those elements and apply them to everything, but they tend to be difficult to pinpoint. The best way to make use of these elements when you can’t identify them directly is to make comparisons between material that you understand well and material that is more challenging. By making these comparisons, the harder material will start to take a shape that makes more sense.

For example, if you understand the behavior of insects like bees but have a hard time remembering organelles, try comparing a beehive to a cell. The outside of the hive itself provides structure as does a cell wall, and worker bees transport nectar to different places in the hive like the endoplasmic reticulum transports materials throughout the cell. The analogy doesn’t need to be perfect or complete, it just needs to organize tougher material in an easier way and serve as a memory aid as you study for and take the exam. This practice may also help with one of the Science Practices (#7), which focuses on making connections within and between different areas of biology.

3) Use strong science practices to train weak content areas and vice versa.

Your strongest science practices likely correspond to strong thinking and learning skills, which you can use to learn difficult or unfamiliar material. For example, imagine that you excel at Science Practice 1 which focuses on using visual representations and models, but you have difficulties grasping how random mutations can lead to specific evolutions. You could modify a family tree to show how natural selection changes the ratio of phenotypes in each successive generation. This would allow you to visualize the important aspects of natural selection without the complications that come with using unfamiliar science practices.

Likewise, the science practices are difficult to study without applying them to a specific content area, so the choice of topic will affect the overall difficulty of the material. Eventually, you will want to be able to apply each practice to any content area, but starting out with a weak practice applied to a confusing content area will create difficulties. Moreover, it will not be clear if the problem is with the science practice or the content area. First, choose your best content area so you can focus exclusively on how to employ the science practice more effectively. When you feel more comfortable, try applying the practice to progressively weaker topics.

Return to the Table of Contents

Wrapping Up

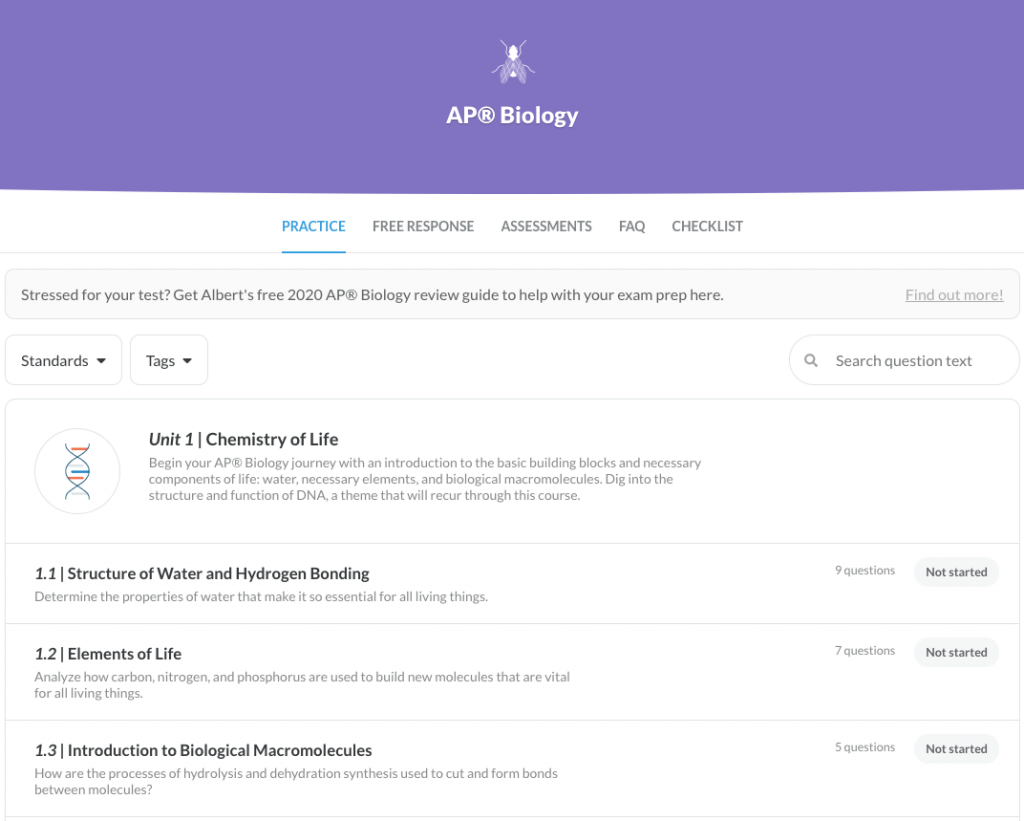

Now that you know how to study for AP® Biology, you might be concerned that planning your studies will be harder than studying itself! It is a lot to consider, but remember that you don’t have to handle everything by yourself. You definitely need to put need in the hours of study, but why not let someone else help with the organization? Albert.io’s AP® Biology section categorizes every question based on the curriculum set by the College Board. You will know immediately which section you are working on, and you can target your studies with ease. There’s even a section for each of College Board’s recommended labs! Take a look for yourself. Albert already has everything you need to hit the ground running.

Need help preparing for your AP® Biology exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Biology practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.