Mechanical energy is a core principle in AP® Physics 1, combining kinetic energy and potential energy to describe an object’s motion and interactions. It is conserved in systems where only conservative forces (like gravity or springs) act, but it can change when nonconservative forces (like friction or air resistance) do work. From a roller coaster accelerating down a track to a pendulum swinging back and forth, mechanical energy explains how objects move and why they speed up or slow down. Mastering this concept is essential for solving problems involving work, energy conservation, and motion analysis on the AP® Physics 1 exam.

What We Review

What is Mechanical Energy?

Mechanical energy is the sum of two main types of energy: kinetic and potential. Essentially, it’s the energy stored and used by objects due to their motion or position.

- Kinetic Energy: This is energy in motion. If an object is moving, it has kinetic energy.

- Potential Energy: This is energy stored in an object due to its position.

Example: Consider a simple pendulum. When at rest, it’s in a potential energy state at the highest point. As it swings down, potential energy changes to kinetic energy.

Kinetic Energy: Understanding Motion

Kinetic energy represents the energy of a moving object. The formula is:

K = \frac{1}{2} mv^2Here, m is mass in kilograms, and v is velocity in meters per second (m/s).

- Factors Affecting Kinetic Energy:

- Mass: Increasing mass increases kinetic energy linearly.

- Velocity: Since velocity is squared, even a small increase in speed causes a much larger increase in kinetic energy.

Example: Calculate the kinetic energy of a 1000 kg car moving at 20 m/s.

Solution:

- Use the formula: K = \frac{1}{2} mv^2 .

- Substitute values: K = \frac{1}{2} \times 1000 \times 20^2 .

- Calculate: K = \frac{1}{2} \times 1000 \times 400 = 200{,}000 \text{ Joules} .

Potential Energy: Energy of Position

Potential energy depends on an object’s position or configuration. Two common types include:

- Gravitational Potential Energy: Energy due to an object’s height above the ground. The formula is:

where m is mass, g = 9.8 \text{ m/s}^2 , and h is height in meters.

- Elastic Potential Energy: Found in stretched or compressed springs.

Example: Calculate the potential energy of a 2 kg book placed on a 3-meter-high shelf.

Solution:

- Use the formula: U_g= mgh .

- Substitute values: U_g = 2 \times 9.8 \times 3 .

- Calculate: U_g = 58.8 \text{ Joules} .

On the AP® Physics 1 exam, students can approximate gravitational acceleration as g = 10 \, \text{m/s}^2 to simplify calculations unless higher precision is required.

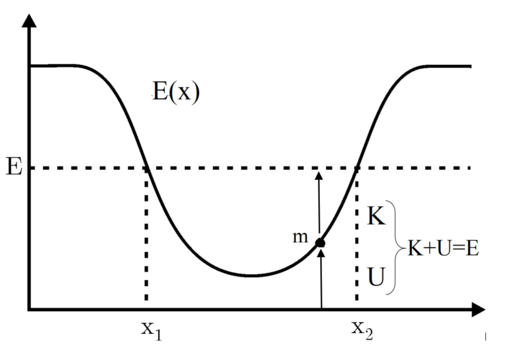

The Conservation of Mechanical Energy

The principle of conservation of mechanical energy states that if no external forces affect a system, its total mechanical energy remains constant. In other words, energy can shift between kinetic and potential forms, but the total remains unchanged.

- Conditions for Conservation:

- Closed Systems: No energy flows in or out.

- Conservative Forces: Only forces like gravity and springs are involved.

Work and Energy Transfer

Work is a crucial concept in understanding how energy transfers between objects. When a force causes a displacement, work is done. It’s given by:

W = Fd\cos\theta- F is the force in newtons.

- d is displacement in meters.

- \theta is the angle between the force and displacement direction.

Example: Calculate work done when a force of 10 N pushes an object 5 m forward with no angle.

Solution:

- Use the formula: W = Fd\cos\theta .

- Substitute values: W = 10 \times 5 \times \cos(0) .

- Calculate: W = 50 \text{ Joules} .

Energy Loss Due to Non-Conservative Forces

When analyzing physical systems, energy transformations occur between kinetic energy and potential energy, but the total mechanical energy is only conserved if no non-conservative forces (such as friction or air resistance) do work on the system. Non-conservative forces dissipate energy into forms like heat, sound, or deformation, reducing the system’s total mechanical energy over time.

Example: Roller Coaster Energy Loss

Consider a roller coaster moving along a track. Initially, it has high potential energy at the top of a hill. As it descends, this potential energy converts into kinetic energy, increasing its speed. However, due to friction between the wheels and the track, as well as air resistance, some of this mechanical energy is lost as thermal energy and sound. This means that:

- The coaster never reaches the same height on the next hill unless additional energy is supplied (e.g., by a motor or chain lift).

- Over time, friction gradually reduces the coaster’s speed, preventing perpetual motion.

This example illustrates how non-conservative forces reduce mechanical energy, requiring external energy input to keep systems moving, a crucial concept in AP® Physics 1 for understanding real-world motion and energy dissipation.

Conclusion: Mechanical Energy

Understanding mechanical energy helps to comprehend the world around us. Concepts like kinetic and potential energy, conservation of energy, and work are foundational to physics. Practice problems solidify these ideas, bridging the gap between classroom learning and real-world applications. Students are encouraged to explore further and deepen their understanding of this essential topic.

| Vocabulary Term | Definition |

| Mechanical Energy | Total energy of motion and position |

| Kinetic Energy | Energy of motion, K = \frac{1}{2}mv^2 |

| Gravitational Potential Energy | Energy due to height, U_g = mgh |

| Conservation of Energy | Total energy remains constant in a closed system |

| Work | Energy transfer due to force, W = Fd\cos\theta |

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Physics 1

Are you preparing for the AP® Physics 1 test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world physics problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

Need help preparing for your AP® Physics 1 exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Physics 1 practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.