Have you ever plucked a guitar string and noticed the intriguing pattern it forms? This pattern is a perfect example of a “standing wave.” In this post, we will learn all about them—what they are, nodes and antinodes, and standing wave harmonics. We’ll explore standing waves through easy-to-understand explanations and examples, focusing on how they relate to music and other everyday situations. So, if you’re a student or just curious, stay tuned to learn more about the incredible world of standing waves!

What We Review

Standing Waves

When we talk about standing waves, we are referring to a phenomenon that occurs when two waves of the same frequency interfere with each other while traveling opposite directions in a medium, often resulting in a vibration pattern that appears to be ‘standing still’. Here, we’ll explore what standing waves are and how they manifest in various situations.

What is a Standing Wave?

Much like the name suggests, a standing wave is a wave that seems to be “standing still” or not moving. Imagine plucking a guitar string. Instead of the wave traveling along the string, it vibrates in place, creating a unique pattern of peaks and troughs. This stationary vibration happens when two waves of the same frequency and amplitude move in opposite directions and interfere with each other. It’s fascinating how these waves superimpose, leading to some parts of the wave seeming still and others vibrating back and forth.

In summary, a standing wave is a vibrational pattern created when two waves of the same frequency travel in opposite directions and interfere with each other. This interference can lead to areas where the medium doesn’t appear to move, known as nodes, and areas where the medium moves with maximum amplitude, known as antinodes.

Nodes and Antinodes

When looking at a standing wave, you might notice points that don’t move at all and others that seem to be vibrating the most. The points that stay still are called “nodes.” Nodes are points along the medium where there is no movement—they are the points of destructive interference. At these points, the two interfering waves are out of phase, meaning the crests of one wave align with the troughs of the other, canceling each other out.

On the flip side, the points with the maximum movement are “antinodes.” Antinodes, on the other hand, are points of constructive interference where the medium exhibits maximum displacement. Here, the interfering waves are in phase, meaning the crests of one wave align with the crests of the other, resulting in amplified wave amplitude.

Harmonics

Now, if you’ve ever played a musical instrument, you might be familiar with the term “harmonics.” Harmonics refers to the various patterns a standing wave can form on a medium. Harmonics are integral multiples of the fundamental frequency of a wave, and they play a crucial role in the formation of standing waves. When a string is plucked or air is blown through a pipe, it can vibrate at several different frequencies simultaneously. Each of these frequencies corresponds to a different mode of vibration, or harmonic, and contributes to the overall sound produced.

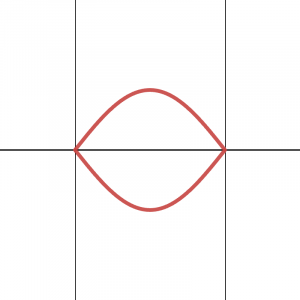

The first harmonic, or the fundamental frequency, is the simplest form of a standing wave and the lowest frequency of vibration of a standing wave. It produces half a wavelength along the length of the string or air column, with a node at each end and an antinode in the center.

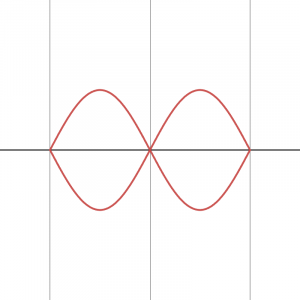

The second harmonic occurs at twice the frequency of the fundamental. In this mode, a full wavelength fits into the string or air column, creating two antinodes and an additional node at the center.

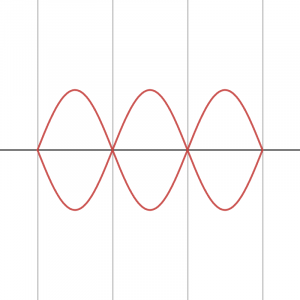

The third harmonic sees the string or air column accommodating one and a half wavelengths, vibrating at three times the frequency of the fundamental.

Open and Closed Pipes

Standing waves can also form in air columns inside pipes, affecting the pitch of the sound produced. An “open” pipe is one that is open at both ends, like a flute. An open pipe produces nodes at both ends and an antinode in the middle. A “closed” pipe, like a clarinet, is closed at one end and open at the other. In open pipes, where both ends are open, antinodes form at each end, while in closed pipes, where one end is closed, a node forms at the closed end, and an antinode forms at the open end.

This distinction between open and closed pipes impacts the harmonics that are produced. Open pipes can produce all harmonics, while closed pipes can only produce odd harmonics. This difference in harmonic production is why a flute (an open pipe) and a clarinet (a mostly closed pipe) sound different when playing the same note.

Applying the Wave Equation to Standing Waves

The wave equation can be applied to understand standing waves better. In a standing wave, the wavelength—representing the distance between two equivalent points of a wave, like from crest to crest—is crucial. To find the wavelength of a standing wave on a string, you can measure the distance between two nodes or two antinodes and then use the relationship L = 2d to calculate the full wavelength. Understanding wavelengths in standing waves is fundamental, especially when studying musical instruments, as it directly relates to the pitch of the note produced.

You can also find the wavelength if you know the harmonic and its length. If you know the length of a string or air column where a harmonic is produced, you can leverage the length-wavelength relationship to determine the wavelength. In the context of the first harmonic, the length corresponds to half the wavelength ( \lambda = 2 L ), as it accommodates only half a wave. For the second harmonic, the length is equivalent to the full wavelength (\lambda = L ). For higher harmonics, the relationship can be generalized as \lambda = \frac{2}{n} L . By applying this relationship, calculating the wavelength from the known length of a harmonic becomes a straightforward task. Let’s try this with some practice problems!

Standing Waves Practice Questions

Try out each of the practice problems below, then scroll down for full solutions!

Practice Question 1

A string is vibrating with a fundamental frequency of 50\text{ Hz}. If the length of the string is 2\text{ meters} and the tension remains constant, what would be the fundamental frequency when the length of the string is reduced to 1.5\text{ meters}?

Practice Question 2

A tube open at both ends resonates at the first harmonic with a frequency of 440\text{ Hz} when the speed of sound in air is 340\text{ m/s}. Determine the length of the tube.

Practice Question 3

Consider a string of length 0.9\text{ meters} fixed at both ends, under tension, displaying its third harmonic. If the wave speed on the string is 160\text{ m/s}, calculate the frequency of the standing wave.

Practice Question 4

An air column in a pipe closed at one end is vibrating in its third harmonic. The speed of sound in air is 343\text{ m/s}, and the frequency of vibration is 170\text{ Hz}. Determine the length of the air column.

Solutions to Standing Waves Practice Questions

Solution: Question 1

A string is vibrating with a fundamental frequency of 50\text{ Hz}. If the length of the string is 2\text{ meters} and the tension remains constant, what would be the fundamental frequency when the length of the string is reduced to 1.5\text{ meters}?

Given the following:

- Fundamental frequency: 50\text{ Hz}.

- Initial length of the string: L_1: 2\text{ meters}.

- Final length of the string: L_2: 1.5\text{ meters}.

- Tension remains constant.

Find the fundamental frequency when the length of the string is 1.5\text{ meters}.

Solution:

We can use the original fundamental frequency and the wavelength to find the wave speed. For a string of length L at its fundamental frequency, the wavelength is 2 L:

\lambda = 2L = 2\cdot 2\text{ m} = 4\text{ m}

So, the speed of the wave on the original length string is:

v = f \cdot \lambda

v = 50\text{ Hz} \cdot 4\text{ m} = 200\text{ m/s}.

With the length reduced to 1.5\text{ m}, the wavelength is 2 \cdot 1.5\text{ m} = 3\text{ m}. Using the wave speed from the previous step, the new fundamental frequency is:

f = \dfrac{v}{\lambda} = \dfrac{200\text{ m/s}}{3\text{ m}} = 67 \text{ Hz}

The fundamental frequency of the string, when its length is reduced to 1.5\text{ meters}, is approximately 66.67\text{ Hz}.

Solution: Question 2

A tube open at both ends resonates at the first harmonic with a frequency of 440\text{ Hz} when the speed of sound in air is 340\text{ m/s}. Determine the length of the tube.

Given the following:

- Frequency: f = 440\text{ Hz}

- Speed of Sound: v = 340\text{ m/s}

Find the length of the tube.

Solution:

First, identify the relationship for an open-ended tube: For a tube open at both ends, the first harmonic occurs when the tube length is one-half the wavelength of the sound.

Use the wave speed equation to find the wavelength:

\lambda = \dfrac{v}{f}

\lambda = \dfrac{340\text{ m/s}}{440\text{ Hz}}=0.77\text{ meters}

The length of the tube is half the wavelength, so:

L = \dfrac{\lambda}{2} = \dfrac{0.773\text{ m}}{2} = 0.39\text{ m}.

The length of the tube is approximately 0.39\text{ meters}.

Solution: Question 3

Consider a string of length 0.9\text{ meters} fixed at both ends, under tension, displaying its third harmonic. If the wave speed on the string is 160\text{ m/s}, calculate the frequency of the standing wave.

Given the following:

- Length of the string: L = 0.9\text{ meters}

- Wave speed: v = 160\text{ m/s}

- Harmonic number: n = 3

Find the frequency of the standing wave.

Solution:

Start by identifying the relationship for the third harmonic. The third harmonic on a string fixed at both ends has 3 half-wavelengths fitting into the length of the string, so L = \frac{3}{2}\lambda.

Rearrange this relationship to find the wavelength:

\lambda = \frac{2}{3} L

\lambda = \frac{2}{3}(0.9\text{ m}) = 0.6\text{ m}

Then, apply the wave speed equation to find the frequency:

f = \dfrac{v}{\lambda}

f = \dfrac{160\text{ m/s}}{0.6\text{ m}} = 267\text{ Hz}

The frequency of the standing wave is approximately 267\text{ Hz}.

Solution: Question 4

An air column in a pipe closed at one end is vibrating in its fifth harmonic. The speed of sound in air is 343\text{ m/s} and the frequency of vibration is 300\text{ Hz}. Determine the length of the air column.

Given the following:

- Speed of sound in air: v = 343\text{ m/s}

- Frequency of vibration: f=300\text{ Hz}

- The pipe is closed at one end and vibrates in its fifth harmonic.

Find the length of the air column.

Solution:

Let’s review the harmonic for pipes that are closed at one end. Since this is the fifth harmonic, the frequency is 5 times the fundamental frequency, and there are \frac{5}{2} wavelengths in the pipe.

Use the wave equation to the wavelength using frequency and speed.

\lambda = \dfrac{v}{f}

\lambda = \dfrac{343\text{ m/s}}{300\text{ m}} = 1.1\text{ m}

The find length of the air column using the harmonic relationship:

L = \frac{5}{2}\lambda

L = \frac{5}{2}(1.1\text{ m}) = 2.8 \text{ m}

The length of the air column, hosting the fifth harmonic, is about 2.8\text{ m}.

Calculating the Speed of Sound Using Standing Waves

Ever wondered how the speed of sound is determined? It’s simpler than you might think! Using a tuning fork and a tube, you can uncover the speed of sound on your own.

Equipment Needed:

- A tuning fork with a known frequency.

- A tube or a graduated cylinder filled with water.

- A ruler or measuring tape.

Procedure:

- Strike the Tuning Fork: Strike the tuning fork against a rubber pad to set it vibrating and producing sound at a known frequency.

- Adjust the Air Column: Hold the vibrating tuning fork over the tube and adjust the water level until the sound is at its loudest, indicating the first resonance. This loud sound means the length of the air column is one-quarter of the sound wave’s wavelength.

- Measure the Air Column: Once you’ve found the first resonance, measure the length of the air column from the top of the tube to the water level accurately.

Calculation:

The length measured is one-quarter wavelengths of the sound wave. To find the actual wavelength, multiply the length of the air column by 4. With the known frequency of the tuning fork and the calculated wavelength, you can now find the speed of sound using the wave equation.

Through this experiment, you’re not just learning about standing waves and resonance in a closed pipe but also applying mathematical relationships to calculate the speed of sound in air. It’s an insightful way to witness theories in action and deepen your understanding of wave mechanics.

Conclusion

We’ve learned a lot about standing waves in this post! We explored what they are, how they form, and where we can find them, like in musical instruments. This post covered critical terms like nodes and antinodes and looked at how standing waves can have different harmonics. We applied mathematical equations to solve practical problems and even learned how to determine the speed of sound through a hands-on experiment. This exploration has hopefully provided a clearer understanding of standing waves!