Introduction to Solubility Rules

In this article, we’re going to teach you all about Solubility Rules. No discussion of solubility rules is complete without first understanding the notation associated with solubility analysis. Understanding solubility on a deep level requires us to view the topic from a particulate approach, which means we will have to discuss the Kinetic Molecular Theory in detail. This will help you understand how compounds become solvated, on a particle level. Once we understand that, there is no stopping us! Thermodynamics is next, with a general discussion about the effects of temperature on solubility. Then, the meat of this article: an in-depth discussion about the solubility equilibrium expression Ksp and what the AP® Exam will require of you. Finally, we will wrap up with a discussion of how inter molecular forces can affect the ability of compounds to become solvated!

Solubility Notation – Essential Knowledge 6.C.3.

There are some notations which you will probably be familiar with already that we must go over before continuing with this guide.

• We sometimes abbreviate the word “precipitate” as “ppt”.

• Solid particles can be designated as (s), i.e. NaCl(s). In a solubility equation, this would equal the precipitate.

• We define soluble products as those who can become solvated in water. In molecular notation this would be designated as (aq), which stands for “solvated in aqueous media”, i.e., Na+(aq).

In general, the higher the temperature of a system the easier it is for compounds to become solubilized in solution. How come? Well, let us consider the system using the Kinetic Molecular Theory.

Total Energy of a System – Essential Knowledge 5.A.1.

Three terms define the total energy of any system.

{ E }_{ total } = KE + PE + U

The first term, kinetic energy (KE), governs the energy an object possesses based on its motion. Macroscopic objects like a moving car have a certain kinetic energy, and microscopic objects like gasses do too. Kinetic energy is a function of the momentum (p) of an object, and momentum is itself a function of the velocity (v) and mass (m) of an object. The greater the mass and the larger the velocity, the greater the momentum, and therefore the greater the kinetic energy. Don’t worry about the calculus; that is just a notation thing.

KE =\int { p } =\int { mv } =\frac { 1 }{ 2 } m{ v }^{ 2 }

The second term, potential energy (PE), is a composite function that describes the energy stored within the system based upon its external conditions. For example, a rock at the top of a mountain has a certain potential energy because it exists inside of a gravitational field, and this field gives it the potential to fall. Likewise, a charged ion (i.e. Na+) has a certain potential energy inside of an electric field. Anytime the word field is mentioned, you can assume that potential energy has something to play in it. Each external force field has its set of equations for potential energy, and we will not be going over them as we speak.

The final term, internal energy (U), is a thermodynamic function that encompasses all the energy associated with the bonds inside of a molecule. The internal energy of a system is affected anytime bonds are made or broken. Absorbing high-energy photons, which cause the electrons in an atom or molecule to jump to a higher-energy state, is also reflected by changes in the internal energy. There are also vibrational and rotational moments in multi-atomic molecules that contribute to the internal energy of a system. Intramolecular forces such as the electric dipole associated with the formation of polar covalent bonds or the magnetic dipole present in aromatic compounds are also classified under changes in internal energy since they are present regardless of external electric or magnetic fields.

To adequately describe the energetic state of a system you need to include all the various functions relating to the variables of kinetic, potential, and internal energy. Many equations compromise the total potential and internal energies of a system, and calculating each one is an incredibly tedious process, if not downright impossible. So, a way to get around this obstacle is only to consider changes in a system. When we do so, we need only consider those variables that are changing between the beginning and end of our reaction.

Kinetic Molecular Theory – Essential Knowledge 2.A.2.

It is easiest to understand the kinetic molecular theory terms of gasses. Let’s say that we place pure helium gas (monoatomic, He) in a container and that we fix the volume of the container. At room temperature (T = 20°C), the gas particles exert a certain pressure on the walls of the container (measured by a barometer). As the temperature drops, what we experimentally observe is that the pressure of the gas in the tank drops in a linear fashion. And what Scottish-born William Lord Kelvin did was extrapolate the linear relationship to the point where the pressure of the gas equals zero. The theoretical temperature that he calculated was -273°C.

So what does this mean? Well, let us consider the energetics argument. What is the total energy of the mono atomic helium gas? Its internal energy is negligible: they have no rotational or vibrational modes, nor does it have a molecular dipole. Inter molecular forces are negligible because the gas molecules are so far apart from each other. Neither does it have any potential energy: the helium molecules are not charged, nor do they possess an inherent magnetic dipole. The only energy that these molecules possess is, in fact, kinetic energy, the energy of motion. Since KE = ½mv2, if the particles have any energy they are moving. So, what happens at the point where the pressure of the container equals zero? At that point, the gas molecules have no energy and therefore have ceased all movement.

What does this all mean? Bottom line: the temperature of a gas is directly proportional to its EK! In liquids, the molecules have a significant amount of intermolecular forces which can also absorb energy. However, this basic understanding of heat equaling movement is the reason why all solubility calculations vary as a function of temperature. Standard measurements are therefore always performed at a certain temperature, such as 25°C so that the calculated value is always true for solubilization at that temperature.

Thermodynamic Considerations of Solubility – 6.C.3.

Applying the Kinetic Theory of Matter to the topic of solubility, we now realize that particles at higher temperatures are excited to higher states of energy, which frequently means and increased number of collisions between these particles. Increased collisions mean that statistically a molecule of water has a greater chance of hitting one of the ions to be solubilized in a way that causes the ion to become solubilized. This applies to any endothermic (heat-absorbing) reaction, which compromises most (but not all) solubilization reactions.

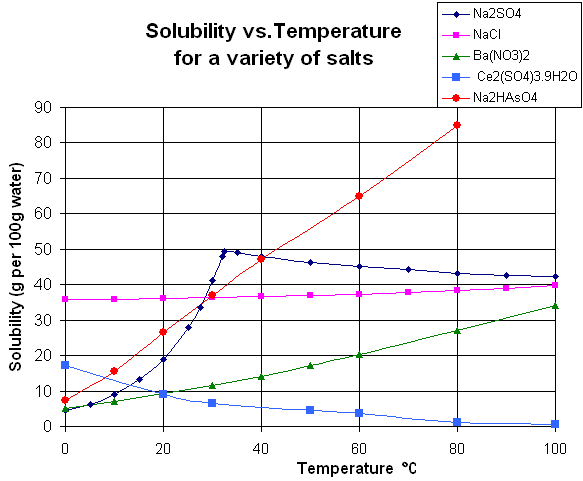

On the other hand, some solvation reactions like that of sodium sulfate are exothermic (heat-releasing) and therefore are less soluble at a higher temperature. A graph of some solubilization constants as a function of temperature is shown below to provide an example.

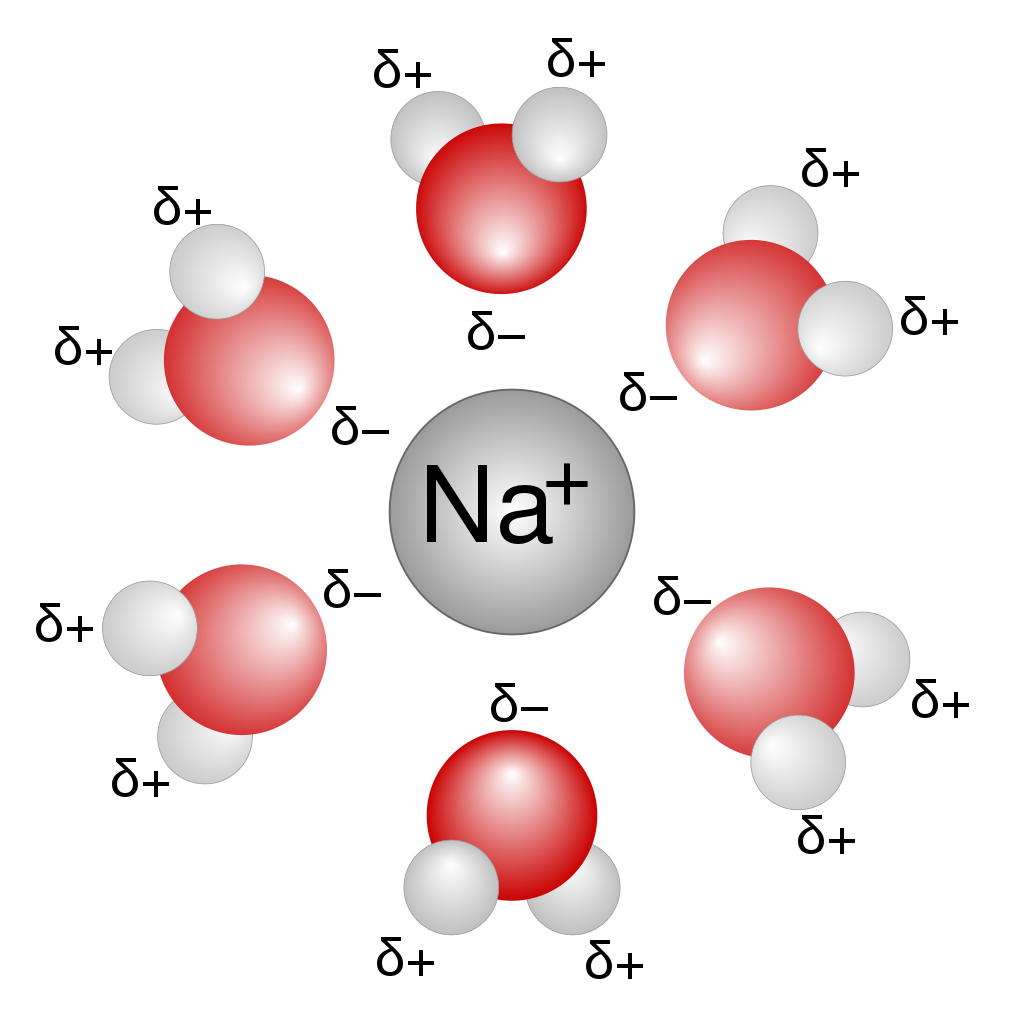

Higher temperature also serves to decrease the attraction between individual water molecules, which are highly attracted to one another. Breaking up the lattice of hydrogen bonds somewhat allows incoming ions to take their place inside the lattice. This can visually be represented as the water molecules around the ion forming a solvation shell.

The Always Soluble’s – Essential Knowledge 6.C.3.

Several salts that are always soluble in water regardless of their composition. All salts which contain the following ions are always soluble:

• Sodium, Na+

• Potassium, K+

• Ammonium, NH4+

• Nitrate, NO3–

Example:

Table salt, NaCl, is completely miscible in water, dissociating completely to its constituent sodium and chloride ions. NaC{ l }_{ (s) }\leftrightarrow { Na }_{ (aq) }^{ + }+{ Cl }_{ (aq) }^{ - }

In the past, you were required to memorize a list of compounds or salts and know from memory whether or not the product was soluble in water, or will form a precipitate. Instead, the new AP® Chemistry exam stresses the understanding of the solubility equilibrium constant, Ksp. To quote from the AP® Chemistry Exam Guide (pg 79):

“Memorization of other ‘solubility rules’ is beyond the scope of this course and the AP® Exam. Rationale: Memorization of solubility rules does not deepen understanding of the big ideas.”

Therefore, we will focus the rest of our discussion on the application of the solubility equilibrium constant.

Solubility Equilibrium Constant – Essential Knowledge 6.C.3.

For the dissolution of a salt, the reaction quotient Q is referred to as the solubility product and Ksp as the solubility-product constant. Why “solubility-product”? Well, let’s use an example to show how we calculate the solubility of an ionic substance in water. For the ionic salt silver chloride (AgCl):

AgC{ l }_{ (s) }\leftrightarrow { Ag }_{ (aq) }^{ + }+{ Cl }_{ (aq) }^{ - }

Writing out the Ksp of the reaction (solubilization) is the same as writing out any other equilibrium constant: the equilibrium constant is the ratio of products and reactants. For a reaction with the form:

aA + bB = cC + dD

The equilibrium expression would be written out as follows:

K = \dfrac { { [A] }^{ a }{ [B] }^{ b } }{ { [C] }^{ c }{ [D] }^{ d } }

However, in the example above, the only reactant is a solid. Solids are excluded from equilibrium expressions. Therefore, the expression for the example (and for any solubility expressions) simplifies to:

{ K }_{ sp }=\left[ { Ag }^{ + } \right] \times \left[ { Cl }^{ - } \right]

This is why the solubility equilibrium constant is called the “solubility-product” constant: because the value of Ksp is always equal to the product of the concentrations of the two constituents of the salt. The value of the equilibrium constant is experimentally-derived and will be given to you on the AP® Exam from a table of standard solubility products. However, it is up to you to know how to use and apply it.

Using the example above, and given Ksp = 1.8 x 10-10, find how many grams of silver chloride can be dissolved in one liter of water.

We would write:

{ K }_{ sp }=1.8\times { 10 }^{ -10 }=\left[ { Ag }^{ + } \right] \times \left[ { Cl }^{ - } \right]

In silver chloride, [Ag+] = [Cl–], so this can be alternatively written as

{ K }_{ sp }=1.8\times { 10 }^{ -10 }={ \left[ { Ag }^{ + } \right] }^{ 2 }

Which when square-rooting both sides simplify to:

\left[ { Ag }^{ + } \right] =1.34\times { 10 }^{ -5 }=\left[ { Cl }^{ - } \right]

Since equilibrium expressions are written in standard units, the number given above is for moles or compound. And since the concentration of silver chloride equals the concentration of silver and chloride ions, one liter of water will solubilize 1.34 x 10-5 moles of AgCl. The molar mass of silver chloride is found to be 143.32 g/mol using the Periodic Table. So converting to grams:

\left( 1.34\times { 10 }^{ -5 }mol \right) \times \left( 143.32g/mol \right) =1.92\times { 10 }^{ -3 }g

One liter of water would solvate 1.92 x 10-3grams of silver chloride.

This calculation becomes a little more algebra-dependent when you deal with non-binary salts (salts that contain more than one positive and one negative ion). An example is the salt lead bromide (PbBr2), which contains two bromide ions for every lead ion.

Given { K }_{ sp }=4.6\times { 10 }^{ -6 }, find how many moles of lead bromide can be dissolved in 500 mL of water.

We would write:

{ K }_{ sp }=4.6\times { 10 }^{ -5 }=\left[ { Pb }^{ 2+ } \right] \times { \left[ { Br }^{ - } \right] }^{ 2 }

When one mole of lead bromide dissolves, two moles of chloride and one mole of lead ions are formed. This can be represented as:

\left[ { Pb }^{ 2+ } \right] =x and \left[ { Br }^{ - } \right] =2x.

This variable ‘x’ is equal to the number of moles of lead bromide being dissolved. We can substitute ‘x’ into our Ksp expression:

{ K }_{ sp }=4.6\times { 10 }^{ -5 }=\left[ { Pb }^{ 2+ } \right] x{ \left[ { Br }^{ - } \right] }^{ 2 }=\left( x \right) \cdot { \left( 2x \right) }^{ 2 }

We then solve the equation for ‘x’:

\left( x \right) \cdot { \left( 2x \right) }^{ 2 }=4.6\times { 10 }^{ -5 }

\left( x \right) \cdot 4{ x }^{ 2 }=4.6\times { 10 }^{ -5 }

4{ x }^{ 3 }=4.6\times { 10 }^{ -5 }

{ x }^{ 3 }=1.15\times { 10 }^{ -5 }

x={ \left( 1.15\times { 10 }^{ -5 } \right) }^{ \dfrac { 1 }{ 3 } }=2.26\times { 10 }^{ -2 }

One liter of water will solubilize 2.26 x 10-2 moles of lead bromide. However, the question was for 500 mL of water. So, we need to divide the value we got by half, which gives us 1.13 x 10-2 moles of lead bromide. This method can be used to solve for the molar quantity of a compound which can dissolve in water.

It’s also important to note that in some cases Ksp value will be reported in logarithmic units (pKsp). Writing the constant in logarithmic notation is used for simplicity. For example,

{ K }_{ sp }\left( AgCl \right) =1.8\times { 10 }^{ -10 }\grave { a } \log { \left( 1.8\times { 10 }^{ -10 } \right) } =-9.74

{ K }_{ sp }\left( { PbBr }_{ 2 } \right) =4.6\times { 10 }^{ -5 }\grave { a } \log { \left( 4.6\times { 10 }^{ -5 } \right) } =-4.34

We want you to note this important trend in solubility-product constants: the smaller (more negative) the equilibrium constant, the less compound can be dissolved in water. This is true both for the regular and logarithmic form of the constant. Analyzing Ksp values is the new way that the AP® Chemistry Exam will test your understanding of Solubility Rules. By being able to predict the favor ability of solvation based on an understanding of the solubility-product constant, this will give you true insight into the deep meaning behind solubility.

Application of Le Chatelier’s Principle – Essential Knowledge 6.C.3.

When performing solubility experiments, one can notice the decreased solubility of certain compounds in the presence of like compounds. For example, sodium chloride is fully soluble in water. However, if you were to try and solubilize a different sodium salt (such as sodium sulfate, Na2SO4) or chloride salt (such as silver chloride, AgCl) the solubility of the second salt would be lower than if you tried to solubilize the salt in a solution of pure water. This is due to the phenomena known as the Common Ion Effect.

In essence, Le Chatelier’s principle predicts that as you change the concentration of a compound on one side of the equilibrium expression, the system will be prompted to adjust for those changes. Using the example above, suppose sodium chloride was dissolved in water as such:

{ NaCl }_{ (s) }\leftrightarrow { Na }_{ (aq) }^{ + }+{ Cl }_{ (aq) }^{ - }

Now, when we go to add silver chloride, instead of the usual reaction quotient Q where the starting concentration of chloride is equal to zero, now the starting concentration of chloride is actually equal to the concentration of dissolved chloride from the NaCl.

{ AgCl }_{ (s) }\leftrightarrow { Ag }_{ (aq) }^{ + }+\uparrow { Cl }_{ (aq) }^{ - }

Le Chatlier’s Principle is applied by arguing that less silver chloride will dissolve in the salt solution because there is already a certain amount of chloride in the solution. In other words, as we increase the concentration of one of the compounds in the reversible reaction, the concentration of the compounds on the other side of the reversible reaction must also increase. This is the core of the Common Ion effect, and it is a topic that you will almost certainly encounter qualitatively at least on the AP® Chemistry Exam.

Molecular Polarity – Essential 2.B.1, 2.B.2, 2.C.1.

When two atoms share a covalent bond but have different electronegativities (0.5 <e–< 2.0) the electrons in the bonds are shared unequally, and the molecular becomes polar. Below is a heat map of electron density, a standard method of displaying bond polarity. The red region is representative of areas with high electron density, and blue represents low density.

The polarity of a molecule directly relates to the manner in which compounds are solvated by water in solution. It can be challenging to predict molecular polarity. Diatomic molecules of the same element are always non polar. Likewise, carbohydrates are generally non polar. Any molecule with mirror planes of inversion cannot be polar because polarity is by definition determined by an uneven distribution of charges. Even in molecules that are symmetrical about an uneven axis, such as boron trifluoride (BF3), which has a trigonal planar shape that is non polar, the overall distribution of charges is symmetrical.

Hydrogen Bonding – Essential Knowledge 2.B.2.

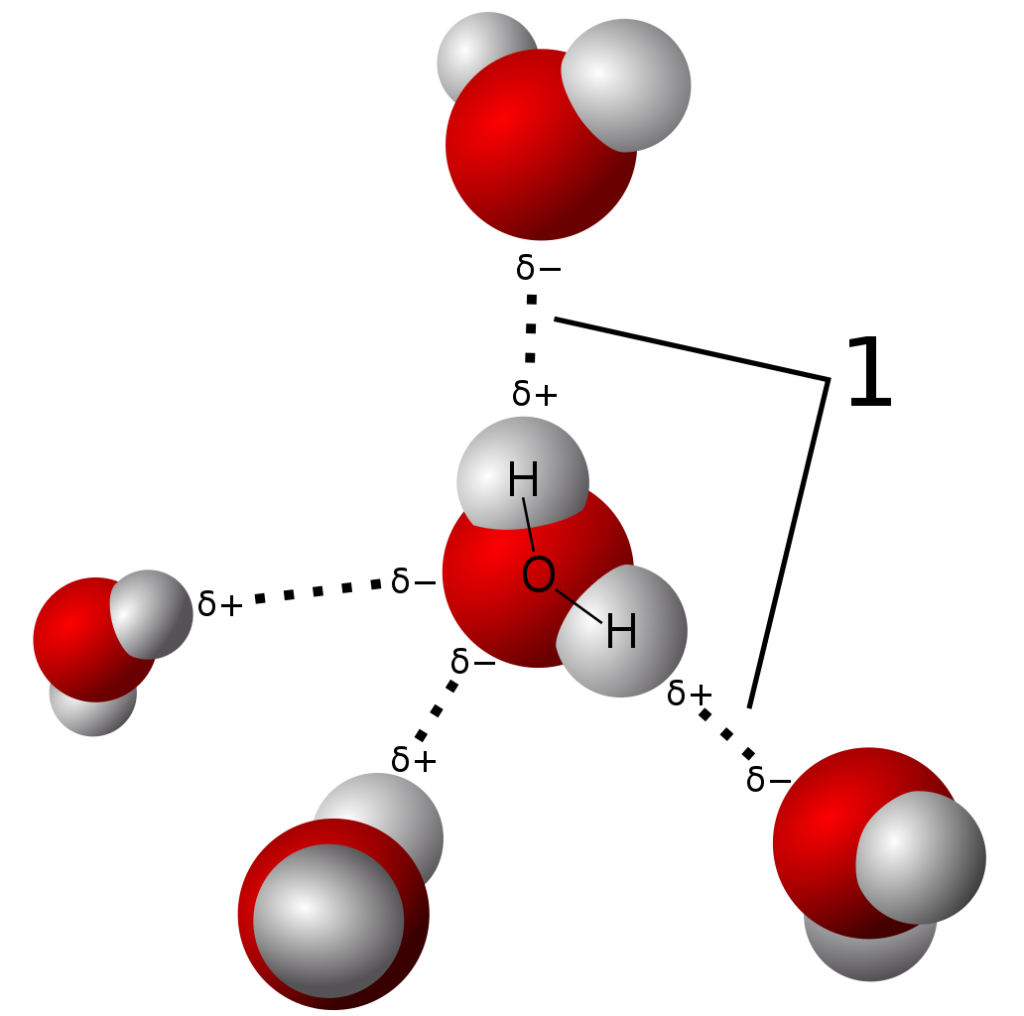

A type of intermolecular bonding is the hydrogen bond, which is a specific type of intermolecular bonding. Below we’ve shown an image of the electron density of a molecule of water, which consists of one oxygen atom bonded to two hydrogen atoms. Oxygen (e– = 3.44) has a much higher electronegativity than hydrogen (e– = 2.20), and therefore the electrons are more attracted to the oxygen atom and spend more time closer to its nucleus. This results in the formation of a polar bond.

Now the water molecule, which is surrounded by other similar molecule, has both a positive and negative partial charge. In a solution of water, the partially positive hydrogen atoms attract the partial negative charge of other oxygen atoms in nearby water molecules, and vice versa. This creates a unique network of weak electrostatic interactions which are aptly named hydrogen bonds.

Unlike the other intermolecular forces, hydrogen bonds are relatively strong though still weaker than ionic and covalent bonds. They are also important because of the sheer number of them in solutions of polar protic (hydrogen-containing) molecules like H2O: they are the main contributor to the physical effect of surface tension in water.

One important final point: hydrogen bonds only exist in protic molecules that are polar. Carbohydrates, which consist of molecules composed of many carbon-hydrogen bonds (as the name implies), do not possess any polarity, and therefore cannot for hydrogen bonds. That is why oils do not dissolve in water!

Effects of pH on Solubility – Essential Knowledge 6.C.3.

The pH of a solution is a measure of the concentration of protons (H+ ions), where the most concentrated protonated solution has pH = 0, and the least protonated (most basic) solution has pH = 14. There is a larger discussion about what constituted an acid and a base, but for now, we will keep the discussion around the Arrhenius definition of acids and bases (H+ and OH– ions).

How does the pH of a solution affect the solubility of a compound? Well, some compounds are neutral at some pH and charge-containing at others. For example, ammonia (NH3) is neutral at basic pH, but, as the concentration of H+ increases, ammonia becomes charged and turns into ammonium (NH4+). Due to the electrostatic interaction between the positive ammonium ion and the partial negative charge of the polar water molecules, ammonium is much more soluble in water than ammonia!

And with that, we are done! You now know everything there is to know about solubility rules for the AP® Chemistry Exam! How did we do? Did we miss anything? If you want to know anything more, or have more specific questions about this topic, write us and let us know! We always appreciate hearing from you, our reader.

Good luck!

Looking for AP® Chemistry practice?

Kickstart your AP® Chemistry prep with Albert. Start your AP® exam prep today.