In 2013, with the introduction of a new exam, the AP® Chemistry community was tossed in a new direction (or so it would seem). Content standards were replaced with Big Ideas, Enduring Understandings, Essential Knowledge and Learning Objectives. The committee of college professors, secondary teachers, and College Board elite sacrificed breadth for depth and away went such topics as Molecular Orbital Theory and Colligative Properties. While topics such as organic chemistry are not explicitly named, their compounds and names continue to show up in questions related to bonding theory and hybridization. With all these changes at work, we suddenly saw the introduction of “Science Practices”, but what exactly are they? In short, “Science Practices” refers to lab experiments and the need to expose our AP® Chemistry students to them.

Where did the Science Practices come from?

In their published document entitled “Science College Board Standards for College Success”, Science Practices are outlined as their attempt to ensure any science student enrolled in an AP® Science course be given the opportunity to predict, problem solve and formulate scientific ideas and thoughts via testable, systematic practices. By providing AP® science students this opportunity, they become stronger critical thinkers and problem solvers using observation and evidence. Can our students collect data? Can they organize their data and analyze it to find patterns and/or trends in the relationship between the manipulated and responding variables? Can they interpret these patterns and trends using graphical or particulate representations in a meaningful way? Are they able to calculate numerical data into equations beyond the rote “plug-and-chug” of a typical mathematical question and provide meaning to those values? Using these relationships, are students able to develop a cognitively reasonable explanation for the phenomena observed? For STEM-related topics, STEM teachers and students, it would seem that these would be reasonable requirements for students to demonstrate true comprehension and understanding of the topic.

What is equally reasonable is the assumption that rigorous amounts of practice via group collaboration and worksheets would accomplish the task as well as labs would. But is this truly a reasonable assumption? AP® Chemistry is more than just memorizing detailed concepts and running numbers through a variety of equations. AP® Chemistry involves integrating these concepts and mathematical ideas in familiar and novel situations in the world around us. How else can students integrate these ideas without actually testing them? Simply put, they can’t. Lab exercises are both important and necessary for AP® Chemistry students in the long range learning process.

More often than not, AP® Chemistry students are asked to justify their choice and/or explain their reasoning throughout the free-response portion of the exam. For example, on the operational exam issued in 2015, question 2(f) described to students a dehydration experiment in which “C2H4 (g) and unreacted C2H5OH (g) passed through a tube into the water. The C2H4 was quantitatively collected as a gas but the unreacted C2H5OH was not. Explain this observation in terms of inter-molecular forces between water and the two gases”[1]

While a strong conceptual knowledge of inter-molecular forces certainly goes a long way in responding to this prompt, the experience students gain from conducting a like-minded experiment solidifies their ability to apply the concept of these forces as it applies to the scientific practice of gas collection. On the same exam with question 3 (e), students then had to replicate a titration curve involving the neutralization of potassium sorbate with hydrochloric acid.

Amongst the mathematical calculations required by this experiment, students were later asked in part (f) to justify their choice in the identifying a particular species with higher concentration. This identification and justification hinged on student comprehension and understanding of the titration curve they developed. How can students explain a particular phenomenon without understanding the scientific concept that supports the idea and providing evidence as a part of that claim? The evidence and understanding that supports their claim arise from the rigorous study of the AP® Chemistry curriculum combined with the laboratory exercise which often leaves a strong, lasting impression on their experiences.

Science Practices are Performance Expectations

Acknowledging the fact that students are required to not only regurgitate chemistry facts as part of their learning but also to support these facts with evidence, it is pretty easy to see that these “Science Practices” are performance expectations. AP® Chemistry students are expected to conduct investigations, to handle equipment, collect data, analyze the data and transform it into meaningful explanations.

Science practices are the driving force that allows an AP® Chemistry student to go beyond rote memorization and engage themselves in true scientific practices that make them question ideas, preconceived notions and findings provided by other disciplines. They must question their own ideas as well as the ideas of others (including you, their AP® Chemistry teacher). By heeding to these expectations, AP® Chemistry students will not only be able to formulate ideas within the AP® Chemistry course but potentially create interlocking ideas across disciplines. How can we understand the conversion of glycogen to glucose in the human body, for example, without a solid understanding of the chemical mechanisms that drives this process? It should be no surprise to any of us that an interdisciplinary consideration works to deepen our understanding of each subject, not just one.

Science Practices Requires Technology

It is fairly well known that technology is NOT equitable across schools in the United States, nor schools within the same state. Heck! Technology is rarely equitable amongst schools in the same district! So before you ask, “How can College Board require technology?”, let us understand that in order for students to make headway in the field of science, they must learn how to use technological tools such as the Internet and analytic balances to determine the accuracy and precision of the measurements that are made. AP® Chemistry students must be able to formulate well-thought out justifications but can only do so if they’re given the opportunity to practice these skills using models or simulations which are readily available on the internet. Moreover, AP® Chemistry students must be able to interpret relationships between two variables but can only do so if they know how to generate and/or manipulate a graph or other mathematical representation which is mostly clearly done using computer-based programs. Even simple qualitative tests, such as the presence of conductivity requires such tools as a light bulb or voltmeter that is capable of making electrical readings. Without overstating the obvious, practicing science requires technology!

Science Practices in AP® Chemistry

More specifically, science practices in AP® Chemistry students must use their chemical knowledge and skill to accomplish a specific goal or task. Together with the Essential Knowledge required by the curriculum, the Science Practices help formulate the Learning Objectives contained within each Big Idea. Take, for example, Learning Objective (LO) 1.6 which states “The student is able to analyze data relating to electron energies for patterns and relationships [See SP 5.1]”. Notice the active terms in that LO: analyze, patterns, relationships that make the seemingly straightforward objective into a robust standard. An AP® Chemistry student who has done nothing more than memorizing the trends or patterns related to ionization energy or electron configuration would be less likely to analyze data for patterns in a significant way to prove the depth of their knowledge in the subject area.

With seven science practices incorporated into the AP® Chemistry curriculum, a student hoping to achieve a 5 will have to use representation and models to communicate and solve scientific problems (SP 1). They will have to use math appropriately and understand unit analysis to ensure the numerical value they cite conveys the meaning they intended (SP 2). With the proper amount of guidance and practice, AP® Chemistry students should be able to extend their thinking into exercises they have designed for themselves within the confines of the AP® Chemistry topic (SP 3 and 4). Upon gathering the data from each particular lab exercise, an AP® Chemistry student should be able to analyze the data, evaluate it for patterns or relationships and evaluate the reliability of the data as it relates to a particular chemical concept (SP 5). Lastly, they should be able to use their data to explain concepts in chemistry (SP 6 and 7).

Science Practices without Labs

Still, some may argue that each of these practices does NOT require AP® Chemistry students to perform labs; that the performance expectation previously mentioned cannot be much of an expectation if the labs are not assessed. After all, we are not going through the work that the International Baccalaureate Organization does in valuing their lab experiences. Often viewed as a competing but related organization, the IBO requires their testing science candidates to submit copies of the labs executed in class. The lab reports are evaluated by outside moderators and assessed with scores based on their internalized rubrics. Upon assessment, up to 25% of the testing candidates’ exam score is predetermined based on the performance shown in these lab exercises. Up to one-fourth of their grade is determined long before they’ve bubbled in their first multiple choice answer. So do science practices really mean lab experiments and exercises for our AP® Chemistry students if they are not being evaluated? Yes!

The idea is not the lab exercises on their own. It is the idea that the lab experiments provide opportunities for our students to translate these abstract ideas into true, authentic experiences. I understand how to drive a stick shift car, for example. I understand that I must depress the clutch and release the gas pedal before changing gears but that understanding does little to prevent the car from stalling when I don’t get the timing right while I’m behind the wheel. The only way I can keep the gears from grinding and the car from stalling is practice. That is what these lab exercises are for our AP® Chemistry students: they are PRACTICE! Our students need to feel the equipment in their hands and guidance in reading new tools. Our students require practice in collecting data and being able to evaluate its validity. They need to be shown the road to connections and patterns as each of these skills are not innately bred into the minds of an AP® Chemistry candidate. One practice problem blurs into the next and students turn a blind eye to one worksheet after another. Lab exercises, however, utilizes the higher order thinking processes of our mind to incorporate a stronger memory of the important concepts outlined in AP® Chemistry curriculum.

In short…

What do the Science Practices mean to AP® Chemistry students? It means higher level learning and comprehension. It means authentic experiences in chemistry. It means interpreting otherwise garbled information into explicit patterns and models that further their understanding of AP® Chemistry. It means AP® Chemistry students are able to construct well thought out, content related explanations that prove they are more than the typical high school chemistry student. It means making several steps towards that ever elusive 5 on the AP® Chemistry exam.

About the Author

Sheila Nguyen has been an educator for over 15 years, having taught a variety of science subjects to middle school, high school and community college students. She has been a Reader with the College Board as well as an Assistant Examiner with the International Baccalaureate Organization since 2003. Most recently, she has continued her work with College Board as a Table Leader and joined the Albert.io team as a content author. When she isn’t teaching introductory and general chemistry courses, she is mother to two very active boys and an active community member in her local area.

[1] “AP® Central – The AP® Chemistry Exam,” College Board, 2015, Accessed 01/21/2016. https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/ap/ap15_frq_chemistry.pdf

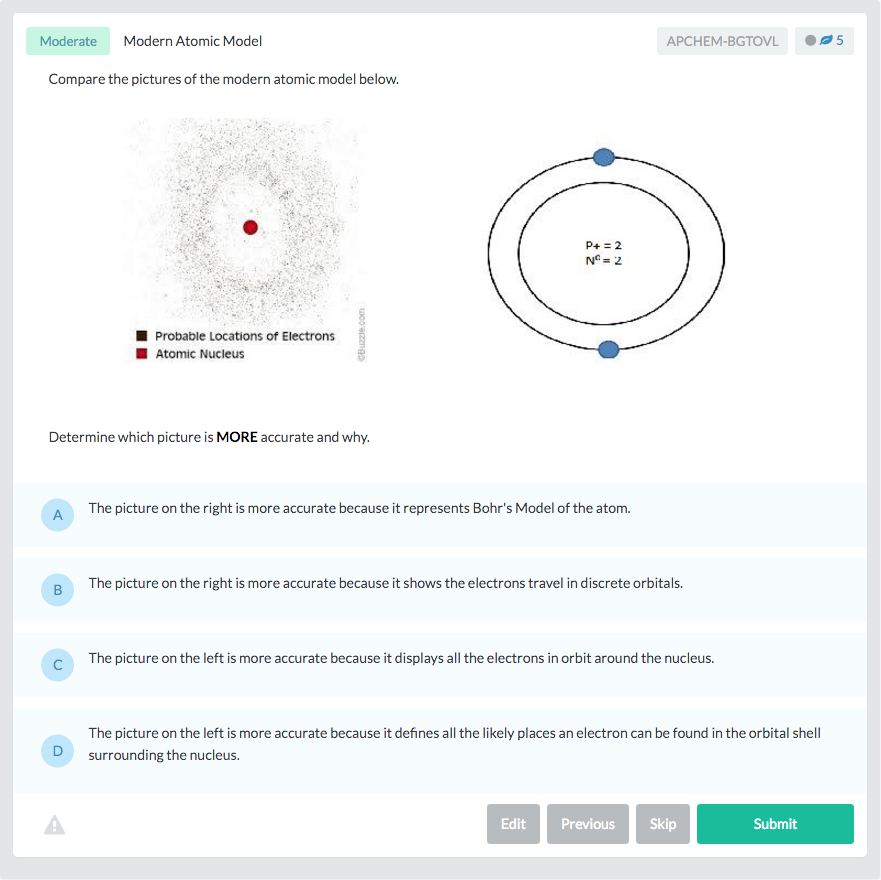

Let’s put everything into practice. Try this AP® Chemistry practice question:

Looking for more AP® Chemistry practice?

Check out our other articles on AP® Chemistry.

You can also find thousands of practice questions on Albert.io. Albert.io lets you customize your learning experience to target practice where you need the most help. We’ll give you challenging practice questions to help you achieve mastery of AP® Chemistry.

Start practicing here.

Are you a teacher or administrator interested in boosting AP® Chemistry student outcomes?

Learn more about our school licenses here.